This article is part of our 2019 contribution to the DC Homeless Crisis Reporting Project in collaboration with other local newsrooms. You can see all of our collective work published throughout the day at DCHomelessCrisis.press and join the public Facebook group to discuss how to act on this information and add context to areas we may have overlooked.

This article is part of our 2019 contribution to the DC Homeless Crisis Reporting Project in collaboration with other local newsrooms. You can see all of our collective work published throughout the day at DCHomelessCrisis.press and join the public Facebook group to discuss how to act on this information and add context to areas we may have overlooked.

On Jan. 23, the District conducted its annual Point-In-Time (PIT) count, a survey conducted nationwide to give a “snapshot” of residents experiencing homelessness on a single night. According to the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments’s analysis of that data, 489 of the 6,521 people experiencing homelessness in D.C. were “transition-age youth,” young adults age 18-24.

However, the D.C. Homeless Youth Census, a separate annual count of local homeless youth that was conducted only four months prior, found there were 1,328 transition-age youth experiencing homelessness in the District. Other than a small window of time, what separated these surveys was the time taken to complete them and the criteria used to determine who was counted as homeless and who was not.

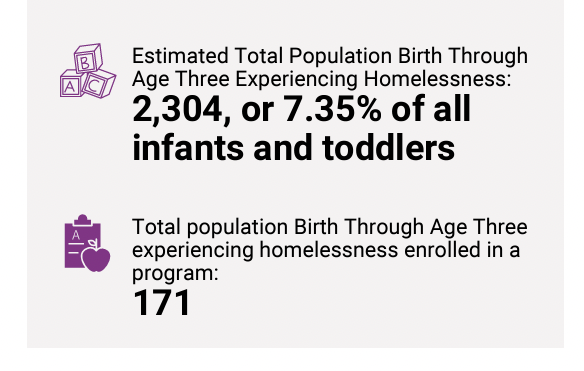

Infographic by Eric Falquero

Regardless of the different demographic sizes, both of these counts are meant to showcase the reality of what homelessness looks like in D.C., and depending on what the numbers suggest, are also how local providers determine how to allocate their services to help alleviate the issue. But when it comes to homeless youth, why don’t the numbers add up?

For Deborah Shore, the director and founder of the homeless services provider Sasha Bruce Youthwork, and other advocates for ending youth homelessness both regionally and nationally, the use of different definitions and methods when conducting these counts is keeping the data from aligning. Because data influence funding, Shore says this discrepancy also restricts the level of care that is available to homeless and unstably housed youth.

Too many definitions, too many methods

The PIT count, which began in 1983, uses the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s standards to determine who counts as homeless and who does not. The HUD definition was last modified in 2012 and requires that a person either be (1) literally homeless, (2) at-risk of becoming literally homeless, (3) homeless under federal law, or (4) fleeing or attempting to flee a situation of domestic violence.

There are some youth that meet the criteria of this definition, but it’s geared more towards people who are on the verge of becoming “chronically homeless,” meaning that a person has been continuously homeless for over a year, or multiple times within the last 3 years, while struggling with a physical or mental disability.

Most people who fit the HUD definition are older than the ages 18-24.

“Young people are in a transition at these ages,” Shore said. “And they’re not in that permanent[ly homeless] status yet, so you don’t want them to be defined as that.”

The District’s youth census uses a broader definition. In addition to literal homelessness as accounted for by HUD, it also considers unstable housing arrangements such as “doubling up” and “couch surfing.”

Along with the definitions, the methodology for each of the two counts is also dissimilar.

The PIT Count takes place one night during the last week of January. Local homeless service providers join in as leaders and outreach specialists, and hundreds of volunteers survey the city for people who are outside, staying in shelters and utilizing day programs from 10 p.m. to 2 a.m.

The Homeless Youth Census, which was established as part of the 2014 End Youth Homelessness Amendment Act, occurs over the course of nine days in September. Like the PIT count, it also utilizes homeless service providers to distribute the survey to anyone 24 and under who is served by their program or agency.

Shore considers the youth census to be a more extensive and in-depth youth count.

“We really utilize youth workers and people who are trusted in the [youth] community to get in there and do the job of finding where kids are.” Shore said.

There is a third unique definition used by the school system, the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act of 1987, a federal law passed to provide urgent assistance and funds for the homeless and homeless programs, which defines homeless youth specifically as youth who lack a fixed, regular, and nighttime residence, or an individual who’s nighttime residence is primarily at either (a) a supervised or publicly operated shelter, (b) an institution of temporary residence for individuals intended to be institutionalized, or (c) a private or public residence not designed for regular sleeping accommodations for human beings.

Following this definition, D.C. Office of the State Superintendent of Education conducts its own count of all homeless youth enrolled in the city’s public schools. Like the youth census, the results also tend to be higher than the numbers recorded by the PIT count.

HUD does take note of other definitions and data collected outside of its realm, not excluding them from its Annual Homelessness Assessment Report, which provides Congress nationwide estimates, characteristics, and trends regarding the state of homelessness and the capacity to provide housing.

Part 2 of the 2017 report, for example, details the national estimates regarding specific demographics, including unaccompanied individuals, families, and unaccompanied youth. It also mentions broader perspectives and how HUD does lean on the information of others to better its own approach to addressing homelessness.

Despite this, the National Law Center on Homelessness said in a 2017 report that the HUD Point-in-Time counts “produce a significant undercount of the homeless population at a given point in time.” The nonprofit advocacy group recommended annual data rather than a one-night snapshot to “account for the movement of people in and out of homelessness over time.

An opportunity for government agencies to get on the same page

Alongside her work with Sasha Bruce, Shore is also on the board of directors for the National Network 4 Youth, an advocacy organization dedicated to preventing and eradicating youth homelessness across the country. Recently, the organization has been advocating for the Homeless Children and Youth Act of 2019, which would require all federal programs to align their definition of homelessness.

“From a big-picture perspective, it’s very hard to tackle homelessness holistically … when the federal programs don’t even define homelessness the same,” said Darla Bardine, executive director for National Network 4 Youth. “And at a local, practical level, it’s very challenging to do systems coordination when the systems have different definitions.”

If passed, the Homeless Children and Youth Act would not only require that HUD change its definition of homelessness, but it would also require that HUD prioritize cost-effective programs that meet the needs of the communities, and improve its data collection on homelessness in order to make children, youth, and families more visible to public and private assistance.

“Vulnerability isn’t determined solely based on where you sleep at night.” Bardine said. “There are young people and families who are temporarily bouncing from place to place — motels, houses — who are extremely vulnerable.”

From the perspective of Bardine and National Network 4 Youth, it’s important that the act be passed because they feel as long as the HUD definition remains the same, the PIT count will continue to produce numbers that hinder the process of systems coordination and prevent youth from receiving the help they need.

There is hardly universal support for this bipartisan legislation, however. Versions of the bill introduced in 2014, 2015, and 2017 all died in previous sessions of Congress.

“I’ve never quite understood the debate since we’ve acknowledged all definitions.” said Brian Sullivan, a public affairs specialist for HUD. According to Sullivan, HUD and other advocates have historically opposed this and similar laws to protect homelessness assistance programs HUD currently funds.

“It’s about targeting scarce resources to where they’re needed.” Sullivan said.

According to him, if the definition were officially broadened, the increase in needs and priorities could derail from HUD’s mission– to create quality communities and provide affordable homes for all.

The National Alliance to End Homelessness shares a similar sentiment, not favoring the Homeless Children and Youth Act. Vice President of Programs and Policy Steve Berg said the law would serve as a “nonsolution” because it would change eligibility requirements for HUD programs and disrupt how they were meant to work.

“Making [families and youth] eligible for a program they wouldn’t benefit from … distracts from what they’re trying to reach,” Berg said. “The solution for families and youth is to create a program that helps them.”

HUD announced today that it would award $75 million in grants towards ending youth homelessness in 23 local communities, including D.C., through the department’s Youth Homelessness Demonstration Program. These communities will be able to invest more into building local systems and providing a range of programs for rapid rehousing, permanent supportive housing, transitional housing, and host homes.

HUD Secretary Ben Carson described the grants as “another critical investment in the futures of our youth, sparing them a life on the streets or in our shelters and placing them on a path to self-sufficiency,” according to the press release.

Great news this morning! We just learned that the District received $4.8M under @HUDgov‘s Youth Homelessness Demonstration Program to support implementation of our youth strategic plan #SolidFoundations. Excited for the opportunity to test some new ideas! https://t.co/7KJZRoFD8Q

— Kristy Greenwalt (@KristyGreenwalt) August 29, 2019

What’s at stake?

On any given Monday evening in Gallery Place, some of the city’s most vulnerable youth come to relax, eat pizza, and watch movies at the First Congregational United Church of Christ at 9th and G streets NW. Sasha Bruce Youthwork runs a drop-in center there from 6 p.m. to 9 p.m. once a week in partnership with the Downtown D.C. Business Improvement District.

“It’s a great collaboration with the businesses that recognize the need,” said Pam Lieber, director of drop-in services for Sasha Bruce. “And rather than try to sweep away, they sought to actively try and remedy it.”

The center was created three years ago in partnership between the church and Sasha Bruce Youthwork as an off-shoot from the organization’s Barracks Row drop-in center, which is open Monday through Friday from 8 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Programs like these are advancements Sasha Bruce has made due to the success and stability of its other core programs. However, during its many years of operation, the organization has also experienced what it’s like to have government funding moved from your program to other priorities, such as Sullivan suggested could happen if HUD’s definition of homelessness is radically expanded.

In 2013, Sasha Bruce lost more than $1.1 million in funding it had previously counted on from the District government. The loss was so drastic, the organization found itself having to turn away youth from its overnight shelter.

“We went from having 26 beds to 5,” Shore recalled.

While there is debate on how federal systems should assess the homelessness crisis, one thing everyone involved seems to agree on is the decision must be made with its impact on funding for existing programs in mind.

And in the case of youth homelessness specifically, whether the solution is changing what assistance youth qualify for or creating new systems to help them — more resources and services are needed to adequately help some of the youngest people experiencing homelessness in the U.S.