When asked why the tent encampments in NoMa are evicted every two weeks, Sean Berry, communications director for the Office of the Deputy Mayor of Health and Human Services (DMHHS) said that the District does not evict the homeless but rather promotes the “health and safety of all District residents, especially those experiencing homelessness.” As part of my Ph.D. research, I have been visiting D.C. encampments since the summer of 2018 and have observed 14 “cleanups” in the NoMa area alone.

Cleanups, from what I have observed, are not for the health and safety of all D.C. residents; instead, they are violent. Not only do these evictions cost the city thousands of dollars, they also disrupt the daily lives of homeless individuals which makes it harder for them to take the steps needed to exit homelessness.

On Jan. 3, the residents of NoMa’s tent encampments were once again forced to move all their belongings outside the cleanup “zone.” I went to help and observe.

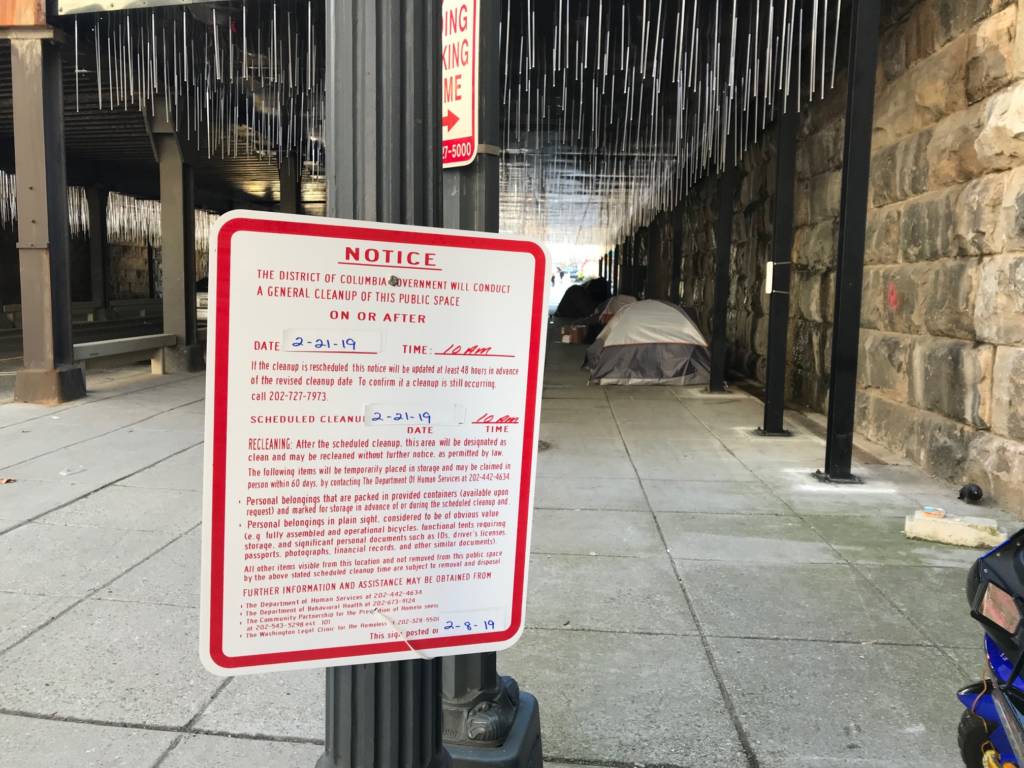

The zone is marked by dozens of white and red signs that state the date and time of the next eviction. Belongings left in the zone, regardless of an individual’s mental or physical health, or prior commitments such as work or court appearances, are subject to disposal. For the homeless, whose entire material possessions are often stored in these zones, this reoccurring process is a source of mental and physical stress.

Evictions generally begin at 10 a.m., but by 9:20 a.m., many homeless residents were already moving their belongings outside the cleanup zone at the K Street NE underpass or “the tunnel.” The zone’s boundaries had expanded, too. After we had moved two large bags of clothing and blankets to a ledge on the corner of K and 2nd Street, a representative from DMHHS told us we could not put our stuff there, pointing to a recently posted sign that indicated we were in a now-larger cleanup zone.

“I used to feel ashamed about all this,” a friend who lives at the encampment told me, as we passed police stationed for the eviction, “then intimidated.” They continued, “Now I don’t feel nothing man, this is harassment, plain and simple.” Although I did not feel the same level of emotional distress as my friend, I was exhausted from moving encampment belongings and constantly avoiding stepping into the traffic so close by.

At 9:50 a.m., people began to get tense, trying to figure out what to move and what to abandon. At 10:03 a.m., we made our last trip. My arms, legs, back, neck, fingers and head ached. As we sat and waited for the cleanup to be over, the exhaustion and pain intensified.

The cleanup crew left at 12:45 p.m. and the tents were set back up. I noticed that the area didn’t look much different than when I’d arrived that morning.

“It’s not like we come to their homes and force them to move all their stuff to the sidewalk,” my friend said before I left. “It’s just ridiculous, it don’t make sense. They say they is helping us, but all they are doing is making us mad and wearing us out. I just don’t get it.”

Later, the Jan. 17 eviction, as well as the one rescheduled for Jan. 24, would both be canceled due to the weather. Without forcing people to move their stuff, city workers simply came through and collected trash, showing that less destructive alternatives are possible. Indeed, my fieldnotes contain numerous observations of encampment residents sweeping their areas and removing trash, a sign that they too desire clean and safe living spaces.

Clean and safe public spaces ought to be a priority, but must it come with such a heavy price tag? It’s not only the thousands of dollars spent, but also the mental, social and physical health of our homeless residents that suggest we can do better. More trash cans or public restrooms make more sense than cleanups. Affordable apartments would be even better.