Three days after her death, Concepcion Piccioto’s protest display still stands.

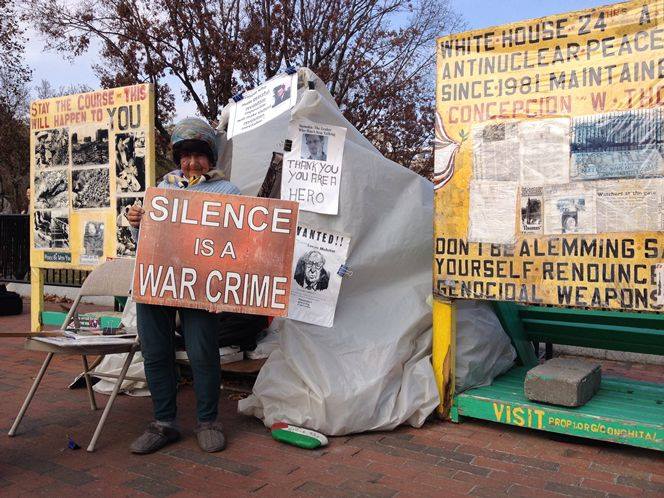

Directly across from the White House, a quiet man named Neil Cousins guards the small shelter covered by a plastic tarp shaking slightly in the wind and surrounded by tall wooden signs. Aside from a few scattered bouquets and a handwritten note reading “Concepcion R.I.P. Love, Philipos,” the 24-hour setup looks very similar to how it has for the past 35 years.

The signs have accumulated and the government critiques have shifted to fit current political issues, but the message overall is still a call for world peace. A number of proclamations and condemnations line the wooden structure of the display, most of them criticizing government violence. “Radioactive Pollution Kills” reads a paper flyer taped to a stack of milk crates. “Don’t be a lemming,” warns another, “Save yourself – renounce genocidal weapons.”

Concepcion Picciotto, who was believed to be in her early 80s, moved to the United States from Spain as a young adult. After a difficult marriage and failed custody battle, she moved to the District of Columbia to protest government violence, which Picciotto believed is the root of injustice and terror in the world. She died on January 25 after more than three decades of constant protest in front of the White House. She spent her last days at N Street Village, a shelter for women.

Picciotto adamantly opposed nuclear warfare and government violence. Despite her loud and abrasive way of protesting, Picciotto’s primary message was one of peace. She was known for feeding LaFayette Square Park’s squirrels and handing out painted “peace rocks” to visitors of her tent.

Willa Morris, a social worker in the District, remembers coming across Picciotto’s protest decades ago. Morris visited D.C. frequently when she was young, and seeing Picciotto outside the White House left a big impression on her.

“I remember she was very articulate about the issues at hand,” Morris recalled, “And she was very passionate. She taught me about the power that one single person can have.” While most of Picciotto’s signs were bold and eye-catching, Morris remembers being especially impressed with several full-color pictures of exploding atomic bombs that she saw as a young person.

Morris believes that witnessing Picciotto’s commitment to peace and change may have had something to do with her own career choice. She remembers how the participation and upkeep of the tent would ebb and flow depending on the time of year and number of volunteers, but Picciotto was a nearly constant presence. “D.C. is a very transient city,” Morris said. “Concepcion’s tenacity allowed people like me to be exposed to her message. Her commitment was remarkable.”

Julie Turner is another local social worker in the area who, like Morris, was influenced by Picciotto. Turner hopes that Picciotto, whom she casually refers to as “Connie,” will be remembered for her message, not her mental state. “It was clear that Connie was mentally ill, but underneath that illness was a grain of truth,” Turner said.

Most articles unfairly place undue importance on Picciotto’s appearance and mannerisms, according to Turner. “Let’s stop talking about all that,” she said. “Let’s talk about the enduring peace movement that Connie stood for.” Turner emphasized that Picciotto protested more than nuclear proliferation and gun control. She opposed the violence of keeping people homeless and hungry, and used her own life as a living protest against homelessness and systemic violence.

Turner believes that reading material written by nonviolent scholars – she mentioned Thomas Merton, Ignatius Loyola, John Dear, the Berrigan Brothers, and Dorothy Day – can provide a better grasp on Picciotto’s ideas. “We would understand why Connie was there.”

Turner also offered a foil to the media’s typical portrayal of Picciotto’s personality. “She was genuinely a kind woman,” Turner said. “She was always making sure [participants in the 2011 Occupy Washington movement] had enough food.”

Picciotto’s method of peace protest was very controversial. Some questioned her sanity, others criticized the way she related to people. Nonetheless, those who knew her- and even those who didn’t – can acknowledge that she was fiercely committed to her message.

“Connie was a peace activist who happened to be mentally ill.,” Turner said. “A lot of people only saw the mental illness part, and because of that, they minimized her. Over the years no one took Connie’s message seriously. She was treated like a sideshow attraction.”

Picciotto defended her ideas for over three decades, persevering through extreme weather, health problems, and verbal and physical abuse.

“Connie didn’t want a social worker, she wanted peace,” said Turner, who had worried about Picciotto’s health and safety outside. “She wasn’t very forthcoming with her personal information. That wasn’t important to her. It was about her message. Connie was there to tell people to stop blowing each other up!”

Picciotto did not live to see the laying down of weapons that she dreamed about. Instead of retiring signs and messages from her display, she was constantly adding new ones. But the fact that Picciotto’s protest did not bring about world peace does not mean that her message should be forgotten. Turner believes that behind Picciotto’s eccentricities, there is still plenty to learn. “Hold fast and steady to your beliefs,” she said. “We can’t all set up tents, but we can take other steps. We can elect officials who can help.”

Turner also encouraged practicing nonviolence on a small scale. Not all violence comes in the form of drone attacks and gunfire. There are systems in place that make it nearly impossible to get medical attention, or a good education, or even enough food. “That’s violence too,” Turner said, “To change that, we can practice nonviolence in our daily lives. We can work to understand what it means to live in peace.”

The future of Picciotto’s protest remains unknown. Will her admirers step in and volunteer to keep the protest running, or will they abandon the tent in favor of a more approachable way of protest? Currently, three of Picciotto’s fellow peace activists are keeping the tent occupied 24 hours a day, but how long will this system last? The upcoming years and impending political scandals will decide. For the moment, the D.C. community and pursuers of nonviolence alike can take Turner’s advice and help to honor the life of Picciotto, a dedicated peace activist who kept her commitment for as long as her life let her.