In April, the hashtag #DontMuteDC gained widespread social media recognition and sparked a new movement following the brief silencing of go-go music that the Shaw MetroPCS store has played outside its doors since 1995. A resident of the Shay, a recently constructed high-end apartment complex, had made complaints that resulted in an order from parent company T-Mobile to bring the store’s speakers inside.

Hundreds of people quickly rallied outside of the store to call for the music be allowed and thousands more took to the streets at the intersection of 14th and U NW in a series of live performances to support the District’s homegrown genre of funk.

According to Natalie Hopkinson, an assistant professor for the Department of Communications, Culture and Media Studies at Howard University, the movement has since grown into a voice for a much larger problem. Although it remains an integral part of the discussion, it’s not just about the music.

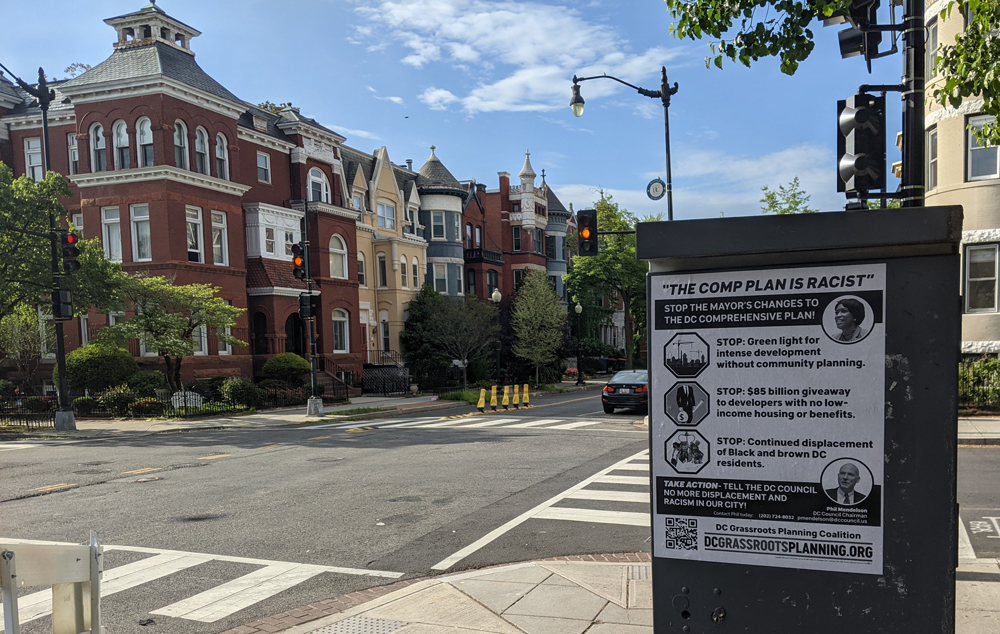

“The big battle over the street corner has since morphed into a conversation about how gentrification has displaced more than 20,000 African-Americans in just over a decade.” Hopkinson said while speaking on a panel last month at the Plymouth Congregational United Church of Christ in Northeast.

Hopkinson was one of four panelists organized by the nonprofit Empower D.C. to discuss gentrification in the District. According to the organization, the effects have led not only to the situation with the MetroPCS store but to the erasure of significant cultural traditions and legacies of Black Americans who have lived in and been increasingly pushed out of the city. A 2017 report by Maurice Jackson, a Georgetown University professor and chair of D.C. African American Affairs Commission, showed that ongoing economic growth and gentrification trends have been disproportionately inhibiting African-American residents since the 1980s.

Much of the panel discussion centered around solutions and the importance of general discourse and community resistance against gentrification. Hopkinson presented a slideshow detailing the origins and progression of the #DontMuteDC movement, including insight on the recent Howard University graduate, Julien Broomfield, who penned the hashtag and the recent tribute led by Regina Hall during the 2019 BET Awards.

“Gentrification can be very depressing to talk about, but it makes me very happy to talk about resistance,” Hopkinson said. “Particularly cultural resistance — and this is what we’re seeing.”

This sentiment was shared by the other panelists, including Shelle Haynesworth, lead creative and owner of the multimedia firm Indigo Creative Works. “I am a storyteller,” Haynesworth said. “And I feel that telling stories can have a very transformative effect on preserving our cultural, historical experience in Washington, D.C.”

Haynesworth’s latest project, “Black Broadway on U,” blends various mediums and cultural storytelling techniques to maintain the history of U-Street, which was once a financially and culturally affluent neighborhood. It was established and predominantly maintained by Black Americans throughout the Jim Crow era.

The main inspiration for the project came from Haynesworth’s grandmother, Lucille Dawson, who felt compelled to open up about her life and the history of U Street after hardly recognizing it when driving down the street with Haynesworth in 2013. Dawson had migrated to the city from Louisiana in 1932 when she was 12. Several of the places she had danced in and worked at while growing up had vanished.

Haynesworth said the shock her grandmother felt by seeing cultural landmarks and history literally erased allowed her to also see the need to share her story.

“It struck me in that moment, the need to capture the stories of our elders,” Haynesworth said, adding that she wasn’t taught any of this history as a young student in D.C. public schools.

In recent years, there have been resources such as the Howard University library and the Washingtoniana collection at the D.C. Public Library that provide books, articles, and more about local D.C. history. But for Haynesworth, it was mostly through family and friends’ stories growing up that she was able to learn about the “breadth and depth” of the neighborhood’s significance during that time.

Michelle Coghill Chatman, an assistant professor for the Crime, Justice, and Security Studies program at the University of the District of Columbia, said being a part of pan-African and Black communities throughout college is how she learned about the Black history of U Street and other areas. She also did her own research.

“For some cultural groups, the passing on of history is a very oral and in-your-face endeavor and it’s not so easy to replicate that online.” Chatman said. “It’s really about lived experience and being in the space with people.”

Chatman has studied the influence of pan-Africanism on several District institutions and businesses, and said gentrification frequently challenges or threatens the cultural identity and history of those spaces.

At the panel, she shared examples from her 2011-2013 dissertation research on how gentrification and demographic shifts in D.C. have affected the ability of Black-owned independent schools and businesses to practice their identity, many of which are gone now.

Blue Nile Botanicals and Ujamaa Shule (School), both of which are in Northwest, participated in Chatman’s research and shared their experiences dealing with new residents and their reactions to the Black-owned establishments.

The owners of Blue Nile, in the Pleasant Plains neighborhood near Howard University, told Chatman that new residents would come in and question their products and practices, despite the store being open for over 30 years. At Ujamaa, located in the area now known as NoMa, the instructors had experienced complaints from new neighbors who were not used to the drumming practices. Afrikan drumming has been a part of the school’s educational system throughout the duration of its operation, alongside instruction in areas such as science, mathematics, health and nutrition, martial arts, and dance.

“People just don’t understand that these are not just buildings and spaces,” Chatman said. “There are relationships and ideas and ideals that are attached to these spaces and it really feels assaulting when people feel that they have to protect their spaces again and again.”

Chatman released a study in 2017 on the impact gentrification has had on the city’s Black churches. She began her reasearch around the 45th anniversary of Elliot Liebow’s “Tally’s Corner: A Study on Negro Streetcorner Men” from 1967. Chatman said the purpose of her study was not to replicate Liebow’s research, which primarily observed the livelihoods of Black men in a then-segregated neighborhood. Instead, she wanted to focus on how that same neighborhood had changed over time, specifically, on the “subtle ways in which Black churches are being pushed out of their communities as a result of political and cultural displacement.”

Chatman interviewed several churchgoers at Mt. Zion Pentacostal Church, which has been in the Logan Circle neighborhood for more than 80 years. Many expressed feeling a sense of aggression and entitlement from new neighbors who seemed “uninterested” in engaging with the cultural or religious institutions of the neighborhood.

“They’re a young population, they’re European-American. And I think along with that sense of entitlement [there is this notion that] ‘what I bring is more important than what you bring,’” said a young woman quoted in Chatman’s research. The woman, Monica Wilkins, had worried over the effects this new attitude would have on people who have lived and worshiped in her community for many years.

“As Black businesses and Black institutions are unable to survive or be supported in D.C., some of that history just disappears along with them, unfortunately.” Chatman said.

Sankofa Video, Books, and Cafe — a Black-owned bookstore in Shaw — has been fighting against similar issues this year, according to Co-owner Shirikiana Gerima. The owners of the 21-year-old establishment recently won a 10-year tax abatement from D.C. Council last month, relieving the business from the area’s rising property taxes for the next decade.

“Why are we being asked to pay $30,000 a year to a city government that’s really doing well at offering abatements to larger corporations?” Gerima said. “Why am I working so hard to put this kind of money aside so that can happen?”

Located near Howard University, Sankofa has been a space for the community to engage in African-centered literature and media. Gerima said that they have “created something we can be proud of” through the store and hopes it will continue to teach and inspire people for as long as possible.

Sabiyha Prince, the membership and political education coordinator for Empower D.C., said the June 24 panel was not meant to be a discussion on whether gentrification is good or bad. Rather, it was meant to call out the damaging effects on the roots of communities and what can or should be done in order to resist them.

Earlier this year, the National Community Reinvestment Coalition released a report that found the District suffered the most widespread low-income displacement of any major central city since 2000.

In an essay Prince wrote in conjunction with that research, she said the issue “begins with targeting low-income, urban communities for discrimination and neglect and ends with ‘improvements’ that exacerbate vulnerabilities that culminate in displacement.”

A recent survey conducted by the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development seems to support her theory. The data shows approximately one fifth of the residents in wards 7 and 8 are anticipating the need to move within three years due to an inability to pay their landlord or bank. The survey also found that Black residents across the city were just over three times as likely to have previously moved on account of “residential instability” than white residents.

Statistics like these are what most of the attendees at the event want to see changed.

“The way that Empower D.C. contributes to that work of preserving Black culture is by fighting to keep the people present,” Prince said. “If the people are here and they represent and engage with the culture, then it’s here. It’s present, it’s natural, it’s organic.”

She said the one good thing gentrification has done is it has encouraged awareness and resistance among the community. Her hope is to ensure that the past, present, and future of Black communities in the District don’t falter under gentrification. Instead, she would like to see them preserved alongside the city’s growth, through new movements, research, community gatherings — whatever it takes.

“The future looks like a city that’s growing with time, but is also inclusive of everyone,“ Prince said.