Public speaking had never come easily for Elouise Hutchinson.

It was especially difficult today — at a memorial service she had organized for her late brother Enzel. As a growing terror gripped her stomach, her eyes fluttered over to the twenty-some relatives and friends who had gathered there: to the clear weekend sky; to the yellowing, spiral-bound pages of a family album; to the sepia photos in a collage she had lovingly tacked together with captions like “Fun Guy” and “Brother.”

What could she possibly say to sum up his life in a matter of minutes? She took a deep breath and began to speak.

“He liked to talk. He liked to laugh. He liked to smile.”

Enzel Sudler was born on Jan. 19, 1960. His sister was 13 months older. His younger brother, Edmund, went to live with a family friend at a young age.

Hutchinson said that she and Sudler were “raised in the sticks by a very religious country woman: my grandmother.” They grew up in a two-story, two-bedroom house with no indoor bathroom just outside the small town of Smyrna, Delaware.

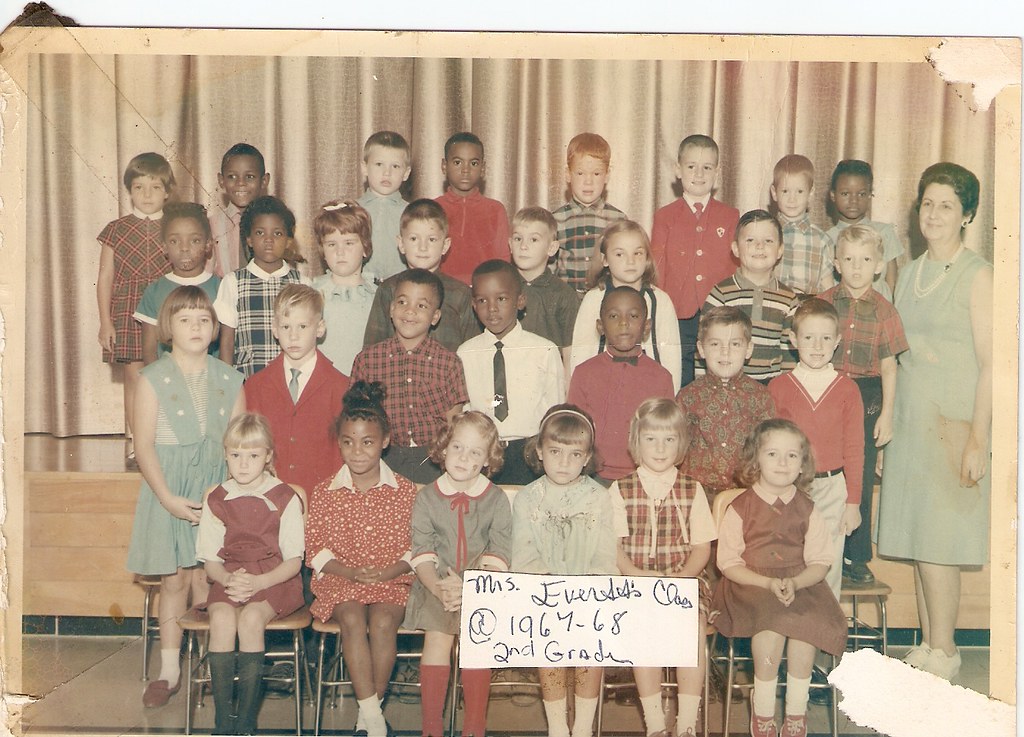

When Sudler was young, he was a Boy Scout and little league baseball player. He was popular in grade school. “He was the person who would get you in trouble for laughing,” Hutchinson said.

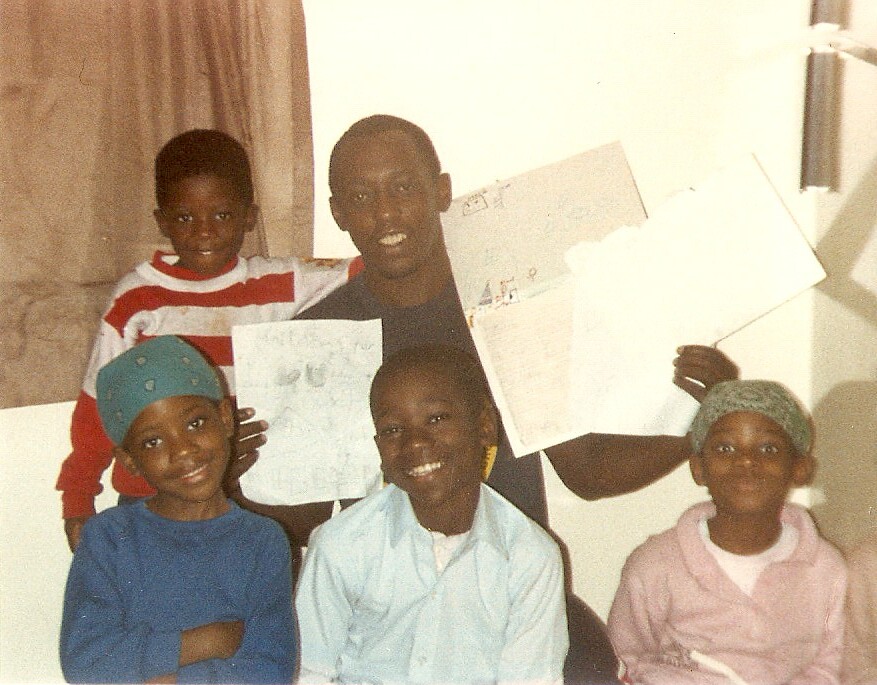

Sudler liked to play practical jokes, like putting smelly shoes underneath his sister’s bed when she was sleeping. Even so, they were close. “We would get laughing,” Hutchinson said. “Certain things between siblings…that are funny and no one else knows they’re funny.”

He was also obsessed with cars. Sudler would spend hours building models. When he was a teenager, he built a black Chevy. Hutchinson was “pretty sure it was never street legal,” but he loved it all the same.

In 1976, their parents got back together and moved to Trenton, New Jersey. Sudler bounced between Trenton and Smyrna. He never graduated high school, but he did have a job in construction for three years in the 1980’s. At one point, he lived with a girlfriend and her children in St. Marys, Georgia. Wherever he was, he was likely to be somewhere else not long after.

Sudler eventually found himself in D.C.– but this time, he stayed.

It is unclear exactly when and how he became homeless. He was very private about it, even with those who were close to him.

In the years leading up to his passing, Sudler spent much of his time at Union Station and on 17th Street. He would talk with friends and run errands for vendors by the metro exit. Once, he was even featured in The National Catholic Register— albeit under the name “Enzio.”

Sudler was faithful, though not Catholic. He started attending Dunn Loring Community Church of God in Virginia around 2005. LaVerne Holland introduced him to the congregation — she used to drive a bus to pick up homeless folks for worship on Sundays. Sudler became almost like an adopted son to her. He ate Christmas dinners with her family. He painted her house. He did odd jobs for other church-goers when he needed money. “He wasn’t scared of work,” Holland said.

When Meg Dominguez moved to D.C. to work as a Senior Clinical Case Manager at Miriam’s Kitchen, Sudler gave her sight-seeing suggestions, like watching planes take off from Gravelly Point. A couple of times, he even went to cheer on Miriam’s Kitchen staff members at marathons.

“He was a really nice light and connected with a lot of people here,” Dominguez said. “Whatever was going on in his life, he made an effort to check in.”

“He was exceptionally lively,” said Beau Stiles, Outreach Services Coordinator at Capitol Hill Group Ministry. He said Sudler liked to tell tall tales and tease people — get them worked up by joking about “cooking ‘possum.”

“I can’t imagine not liking him,” Stiles said.

LaVerne Holland echoed this sentiment. “He liked to talk. He liked to laugh. He liked to smile.” She paused, lost in the memory. “He had a nice smile.”

Things Fall Apart

It seemed like everything was finally coming together. Sudler had stopped drinking. He had gotten a cell phone. He was set to sign a lease for permanent supportive housing the next day.

And then, in late September, things fell apart.

“I always had this feeling I was gonna get a call,” said Hutchinson. But it still knocked the wind out of her when Holland told her that Sudler was in the hospital after a substantial stroke.

Hutchinson hadn’t spoken to her brother in over 10 years—they’d had a falling out the night before their mother’s funeral in January 2006. Now, she needed to make up for lost time.

The first week, Hutchinson thought her brother understood what she said. He would make eye contact, nod, squeeze her hand and follow her with his eyes when she left.

Even when he became unresponsive; even when his body started to shut down; even when it became clear that he wasn’t going to get better, she kept talking. She talked about the things they loved in their childhood. She talked about the things she regretted now that they had grown. “At least I got to apologize,” she said.

Sudler passed away on Oct. 1.

Not long after, Hutchinson organized a memorial service on a sunny afternoon at Ebeneezer’s Coffeehouse by Union Station. She shared her memories of her brother, as did the twenty-some relatives and friends who had gathered there. One of Sudler’s friends stood up and sang to his memory—in notes not somber, but celebratory.

Elouise said that the man stopped her after the program to thank her for honoring Sudler’s life and passing. Now, at least he wouldn’t be forgotten.

This memorial is part of an ongoing effort to honor the lives of those who passed away without a home in Washington, D.C. To learn more, visit streetsense.org/obits.