Ex-convicts gathered for a Congressional briefing on September 17, 2015 to discuss the financial and emotional cost of incarceration for poor families.

Panelists from Washington, D.C., Chicago, Jacksonville, Los Angeles and San Francisco discussed the brand new report “Who Pays?,” which was released the day before by the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights in collaboration with Forward Together and 20 other community organizations.

Some speakers had been incarcerated, while others for relatives inside prison walls. Also represented were volunteers and staff from organizations that help families and incarcerated people.

“Who Pays?” surveyed 1500 incarcerated people, family members of formerly-incarcerated people, employers and other individuals affected by incarceration. The hidden costs for families was the focus of the report.

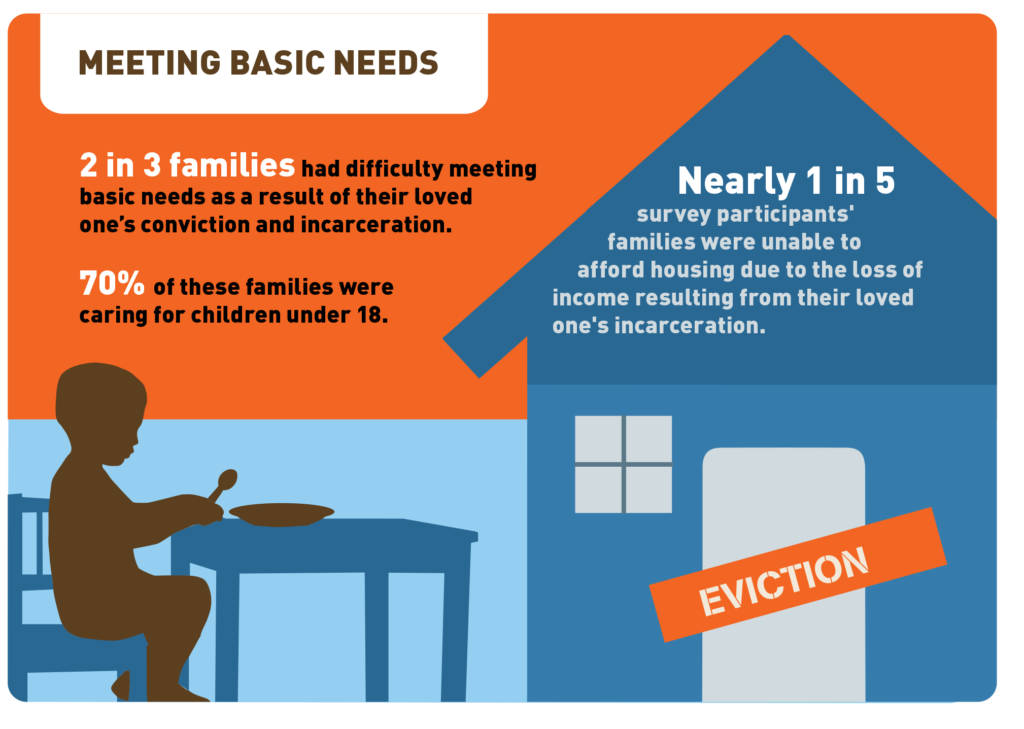

Seventy percent of families surveyed included children under the age of 18 when a member became incarcerated.

Most of the panelists had struggled financially and even gone into debt to travel the distance from their homes to prison for visitation. According to the report, families that regularly visit a relative in prison often have to reprioritize their finances to make the visits possible. In the end, this becomes a spiral of deeper problems for poor families who already choose between rent, food and education.

“Incarceration is both a predictor and a consequence of poverty,” states the report. It references a Bureau of Justice Statistics Special Report showing more than half of people entering the criminal justice system live at or below the poverty line for an individual: $11,770 annual income.

The panel discussed how reforms related to housing and school could make it easier for these families, who have often lost a wage earner to incarceration.

Providing more support during re-entry was also suggested to help get returning citizens back on track. When someone has a prison record, it is more difficult to find a job or to qualify for government-sponsored housing. Sherman Justice, a Washingtonian who was incarcerated for five years, said he received more support in prison than he did during re-entry.

In prison, Justice had help obtaining an email address, making a resume and cover letter, and obtaining other computer skills. Once back in society, he felt that no one cared to help him pursue career opportunities.

“The natural thing to do is to return to your comfort zone. Rather than engaging in the same activities that would inevitably lead me back in handcuffs, I made a conscious decision to change my life around,” Justice was quoted in “Who Pays?”

He stressed the importance of returning to church, working with a personal mentor and the kindness of his grandmother. Today Justice works to empower others through The Reentry Network for Returning Citizens.

When the discussion was over it was clear that there is a strong link between incarceration and poverty. One aspect of that link is that the criminal justice system punishes more than just those people inside the prison walls.