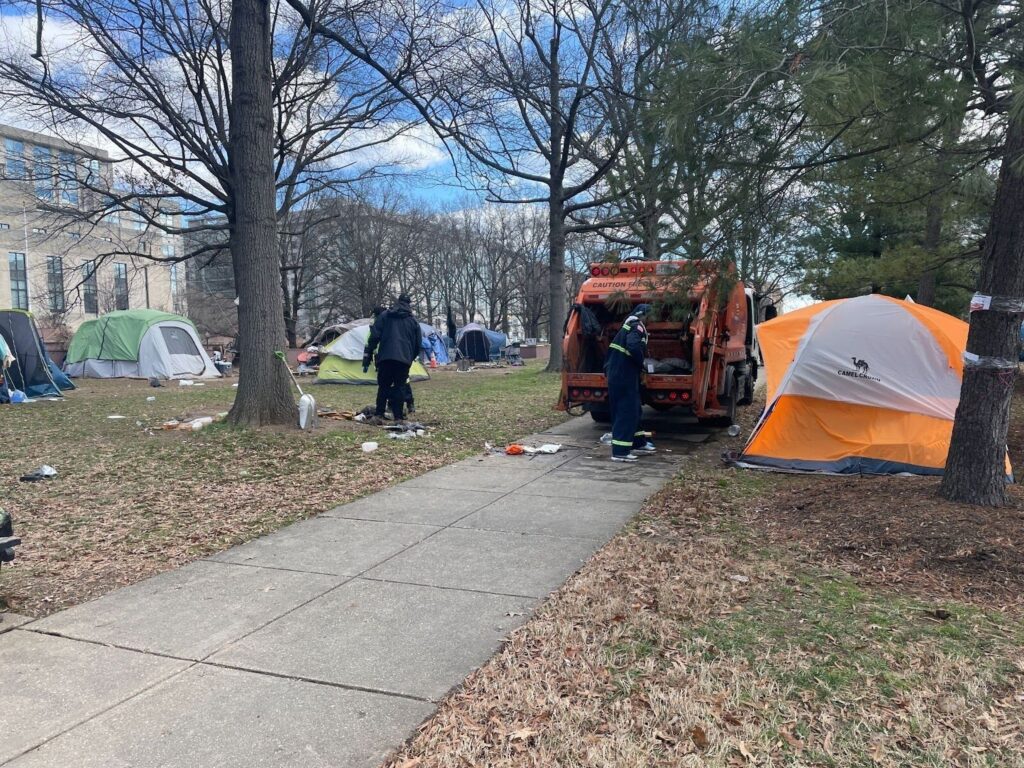

Early January’s unseasonably warm temperatures were a reprieve for homeless people who often are vulnerable to hypothermia this time of year. But the season is far from over, and if December’s brief cold snap was any test, flaws in D.C.’s 2004-2005 hypothermia plan will leave many among the area’s growing number of homeless out in the cold this winter.

Since the official hypothermia season began Nov. 1, the city has declared 18 hypothermia days. These warnings are issued when temperatures fall below 32 degrees – when people living on the street risk frostbite, visual impairment and even death from cold temperatures. The most severe cold to date was experienced in late December when temperatures fell regionwide, reaching a low of 11 degrees with wind chills as low as 10 degrees below zero. Service providers at more than a dozen permanent, seasonal and overflow shelters reported increases in the number of homeless people seeking protection from the cold. Some sites such as La Casa Shelter in Ward 4, filled to capacity and set up extra cots to avoid turning people away.

Mary Ann Luby, outreach director at the Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless, said that two homeless men’s death in December, one found outdoors in an alley at the 1300 block of H Street, NE and one found on 16th Street in Silver Spring, Md., may have been caused by hypothermia, though no official findings have been released concerning the causes of death.

Ruth Walker, program director with the United Planning Organization (UPO), a nonprofit that runs the city’s hypothermia transportation program and hotline (1-800-535-7272), said that the hotline call volume is on the rise. In October, UPO fielded 800 calls from people seeking shelter from the cold. In December, that number rose to 1,227, and by early January the organization had handled 1,672 calls. These numbers are bigger than last year’s figures, said Walker, because the number of homeless in D.C. is increasing.

Workers at area shelters reported experiencing a host of small problems during the first cold snap this season, including a loss of heat and water at some sites. They also worried that a lack of transportation and uneven shelter locations will make this winter difficult for the city’s expanding homeless population.

Luby reported that the shelter in the 801 East Building at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Northeast lacked heat on one of the coldest days of the season, Dec. 20, and also cited continuing heat problems in the Crummel trailers at the New York Avenue site and the MLK trailers near St. Elizabeth’s. Other shelter workers noted that the women’s shelter that recently opened in D.C. General Hospital briefly lacked water in early December. However, outreach workers cautioned that homeless people will be facing even more fundamental issues this winter.

With the D.C. City Council’s vote (on Dec. 21) to close the Randall School Shelter, the city is committing itself to transporting people to other shelters,” Luby said. “The problem is that the city is taking vans that usually do or could do outreach and is giving them a transportation function, reducing outreach efforts.”

UPO has six vans available for night distribution of blankets and supplies and for bringing people to shelters, and two available for morning transportation. However, the same vans are used for both transportation and what Walker call “information services” — when drivers talk to homeless people, trying to convince them to seek shelter.

Chapman Todd, regional director for housing and support services with Catholic Charities, characterizes this kind of one-on-one, personal outreach as essential to building credibility and trust among the hardest-to-reach members of the homeless community who rarely frequent shelter and often are most vulnerable to hypothermia.

Yet the number of UPO vans has not increased in the past two years, even though the Metropolitan Council of Governments reported in June 2004 that the number of homeless people in the D.C. area increased in 2003 for the fourth consecutive year. While Walker maintains that UPO’s services will remain the same this winter and that the organization is committed both to transportation and information outreach, critics of the recent Randall closing argues that, by encouraging downtown homeless people to take vans to the 801 East shelter rather than accommodating them downtown, the city is placing even more pressure on scarce outreach resources.

Impractical and uneven shelter locations also squeeze resources, according to outreach workers. “There are more shelter beds available this winter than last year,” said Todd, “but the concern is where the beds are located. There are not enough downtown spaces.”

Marny Brady, director of advocacy and community building with Neighbors Consejo, the Ward 4 bilingual social service organization, provided a case in point. Sacred Heart, a 25-bed shelter in Ward 4, regularly fills up by 8 p.m. in the winter. People line up outside the shelter doors, Brady said, hoping for vans to take them to other shelters, often not fully aware of where those other shelters are located or unable to walk to those sites themselves. “It would be beneficial to have UPO focus on people on the streets, rather than on shuffling people between shelters,” she added.

Only one hypothermia shelter exists in Ward 3, a 10-bed site at St. Luke’s at Calvert and Wisconsin that just opened on Dec. 16. Other areas, such as Ward 7, have no shelters. Although Ward 1 in Northwest has a “huge, high concentration of homeless,” according to Brady, the ward has only 150-155 beds available for people seeking shelter from the cold, while wards 5, 6 and 8 each have more than 600 beds.

The increasing unevenness of shelter available is a major concern, said Luby. Many homeless people are unwilling to leave their neighborhoods and familiar surroundings, even to avoid frigid temperatures, she said. That problem is only compounded by an increase in the District’s homeless population that is far outpacing the resources available to reach and shelter people, even in the dead of winter, she added.

“The city needs to realize,” argued Luby, “that by opening shelters where people don’t go, (city leaders) are placing the shelters out of reach.”

Early January’s unseasonably warm temperatures were a reprieve for homeless people who often are vulnerable to hypothermia this time of year. But the season is far from over, and if December’s brief cold snap was any test, flaws in D.C.’s 2004-2005 hypothermia plan will leave many among the area’s growing number of homeless out in the cold this winter.

Since the official hypothermia season began Nov. 1, the city has declared 18 hypothermia days. These warnings are issued when temperatures fall below 32 degrees – when people living on the street risk frostbite, visual impairment and even death from cold temperatures. The most severe cold to date was experienced in late December when temperatures fell regionwide, reaching a low of 11 degrees with wind chills as low as 10 degrees below zero. Service providers at more than a dozen permanent, seasonal and overflow shelters reported increases in the number of homeless people seeking protection from the cold. Some sites such as La Casa Shelter in Ward 4, filled to capacity and set up extra cots to avoid turning people away.

Mary Ann Luby, outreach director at the Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless, said that two homeless men’s death in December, one found outdoors in an alley at the 1300 block of H Street, NE and one found on 16th Street in Silver Spring, Md., may have been caused by hypothermia, though no official findings have been released concerning the causes of death.

Ruth Walker, program director with the United Planning Organization (UPO), a nonprofit that runs the city’s hypothermia transportation program and hotline (1-800-535-7272), said that the hotline call volume is on the rise. In October, UPO fielded 800 calls from people seeking shelter from the cold. In December, that number rose to 1,227, and by early January the organization had handled 1,672 calls. These numbers are bigger than last year’s figures, said Walker, because the number of homeless in D.C. is increasing.

Workers at area shelters reported experiencing a host of small problems during the first cold snap this season, including a loss of heat and water at some sites. They also worried that a lack of transportation and uneven shelter locations will make this winter difficult for the city’s expanding homeless population.

Luby reported that the shelter in the 801 East Building at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Northeast lacked heat on one of the coldest days of the season, Dec. 20, and also cited continuing heat problems in the Crummel trailers at the New York Avenue site and the MLK trailers near St. Elizabeth’s. Other shelter workers noted that the women’s shelter that recently opened in D.C. General Hospital briefly lacked water in early December. However, outreach workers cautioned that homeless people will be facing even more fundamental issues this winter.

With the D.C. City Council’s vote (on Dec. 21) to close the Randall School Shelter, the city is committing itself to transporting people to other shelters,” Luby said. “The problem is that the city is taking vans that usually do or could do outreach and is giving them a transportation function, reducing outreach efforts.”

UPO has six vans available for night distribution of blankets and supplies and for bringing people to shelters, and two available for morning transportation. However, the same vans are used for both transportation and what Walker call “information services” — when drivers talk to homeless people, trying to convince them to seek shelter.

Chapman Todd, regional director for housing and support services with Catholic Charities, characterizes this kind of one-on-one, personal outreach as essential to building credibility and trust among the hardest-to-reach members of the homeless community who rarely frequent shelter and often are most vulnerable to hypothermia.

Yet the number of UPO vans has not increased in the past two years, even though the Metropolitan Council of Governments reported in June 2004 that the number of homeless people in the D.C. area increased in 2003 for the fourth consecutive year. While Walker maintains that UPO’s services will remain the same this winter and that the organization is committed both to transportation and information outreach, critics of the recent Randall closing argues that, by encouraging downtown homeless people to take vans to the 801 East shelter rather than accommodating them downtown, the city is placing even more pressure on scarce outreach resources.

Impractical and uneven shelter locations also squeeze resources, according to outreach workers. “There are more shelter beds available this winter than last year,” said Todd, “but the concern is where the beds are located. There are not enough downtown spaces.”

Marny Brady, director of advocacy and community building with Neighbors Consejo, the Ward 4 bilingual social service organization, provided a case in point. Sacred Heart, a 25-bed shelter in Ward 4, regularly fills up by 8 p.m. in the winter. People line up outside the shelter doors, Brady said, hoping for vans to take them to other shelters, often not fully aware of where those other shelters are located or unable to walk to those sites themselves. “It would be beneficial to have UPO focus on people on the streets, rather than on shuffling people between shelters,” she added.

Only one hypothermia shelter exists in Ward 3, a 10-bed site at St. Luke’s at Calvert and Wisconsin that just opened on Dec. 16. Other areas, such as Ward 7, have no shelters. Although Ward 1 in Northwest has a “huge, high concentration of homeless,” according to Brady, the ward has only 150-155 beds available for people seeking shelter from the cold, while wards 5, 6 and 8 each have more than 600 beds.

The increasing unevenness of shelter available is a major concern, said Luby. Many homeless people are unwilling to leave their neighborhoods and familiar surroundings, even to avoid frigid temperatures, she said. That problem is only compounded by an increase in the District’s homeless population that is far outpacing the resources available to reach and shelter people, even in the dead of winter, she added.

“The city needs to realize,” argued Luby, “that by opening shelters where people don’t go, (city leaders) are placing the shelters out of reach.”

Early January’s unseasonably warm temperatures were a reprieve for homeless people who often are vulnerable to hypothermia this time of year. But the season is far from over, and if December’s brief cold snap was any test, flaws in D.C.’s 2004-2005 hypothermia plan will leave many among the area’s growing number of homeless out in the cold this winter.

Since the official hypothermia season began Nov. 1, the city has declared 18 hypothermia days. These warnings are issued when temperatures fall below 32 degrees – when people living on the street risk frostbite, visual impairment and even death from cold temperatures. The most severe cold to date was experienced in late December when temperatures fell regionwide, reaching a low of 11 degrees with wind chills as low as 10 degrees below zero. Service providers at more than a dozen permanent, seasonal and overflow shelters reported increases in the number of homeless people seeking protection from the cold. Some sites such as La Casa Shelter in Ward 4, filled to capacity and set up extra cots to avoid turning people away.

Mary Ann Luby, outreach director at the Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless, said that two homeless men’s death in December, one found outdoors in an alley at the 1300 block of H Street, NE and one found on 16th Street in Silver Spring, Md., may have been caused by hypothermia, though no official findings have been released concerning the causes of death.

Ruth Walker, program director with the United Planning Organization (UPO), a nonprofit that runs the city’s hypothermia transportation program and hotline (1-800-535-7272), said that the hotline call volume is on the rise. In October, UPO fielded 800 calls from people seeking shelter from the cold. In December, that number rose to 1,227, and by early January the organization had handled 1,672 calls. These numbers are bigger than last year’s figures, said Walker, because the number of homeless in D.C. is increasing.

Workers at area shelters reported experiencing a host of small problems during the first cold snap this season, including a loss of heat and water at some sites. They also worried that a lack of transportation and uneven shelter locations will make this winter difficult for the city’s expanding homeless population.

Luby reported that the shelter in the 801 East Building at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Northeast lacked heat on one of the coldest days of the season, Dec. 20, and also cited continuing heat problems in the Crummel trailers at the New York Avenue site and the MLK trailers near St. Elizabeth’s. Other shelter workers noted that the women’s shelter that recently opened in D.C. General Hospital briefly lacked water in early December. However, outreach workers cautioned that homeless people will be facing even more fundamental issues this winter.

With the D.C. City Council’s vote (on Dec. 21) to close the Randall School Shelter, the city is committing itself to transporting people to other shelters,” Luby said. “The problem is that the city is taking vans that usually do or could do outreach and is giving them a transportation function, reducing outreach efforts.”

UPO has six vans available for night distribution of blankets and supplies and for bringing people to shelters, and two available for morning transportation. However, the same vans are used for both transportation and what Walker call “information services” — when drivers talk to homeless people, trying to convince them to seek shelter.

Chapman Todd, regional director for housing and support services with Catholic Charities, characterizes this kind of one-on-one, personal outreach as essential to building credibility and trust among the hardest-to-reach members of the homeless community who rarely frequent shelter and often are most vulnerable to hypothermia.

Yet the number of UPO vans has not increased in the past two years, even though the Metropolitan Council of Governments reported in June 2004 that the number of homeless people in the D.C. area increased in 2003 for the fourth consecutive year. While Walker maintains that UPO’s services will remain the same this winter and that the organization is committed both to transportation and information outreach, critics of the recent Randall closing argues that, by encouraging downtown homeless people to take vans to the 801 East shelter rather than accommodating them downtown, the city is placing even more pressure on scarce outreach resources.

Impractical and uneven shelter locations also squeeze resources, according to outreach workers. “There are more shelter beds available this winter than last year,” said Todd, “but the concern is where the beds are located. There are not enough downtown spaces.”

Marny Brady, director of advocacy and community building with Neighbors Consejo, the Ward 4 bilingual social service organization, provided a case in point. Sacred Heart, a 25-bed shelter in Ward 4, regularly fills up by 8 p.m. in the winter. People line up outside the shelter doors, Brady said, hoping for vans to take them to other shelters, often not fully aware of where those other shelters are located or unable to walk to those sites themselves. “It would be beneficial to have UPO focus on people on the streets, rather than on shuffling people between shelters,” she added.

Only one hypothermia shelter exists in Ward 3, a 10-bed site at St. Luke’s at Calvert and Wisconsin that just opened on Dec. 16. Other areas, such as Ward 7, have no shelters. Although Ward 1 in Northwest has a “huge, high concentration of homeless,” according to Brady, the ward has only 150-155 beds available for people seeking shelter from the cold, while wards 5, 6 and 8 each have more than 600 beds.

The increasing unevenness of shelter available is a major concern, said Luby. Many homeless people are unwilling to leave their neighborhoods and familiar surroundings, even to avoid frigid temperatures, she said. That problem is only compounded by an increase in the District’s homeless population that is far outpacing the resources available to reach and shelter people, even in the dead of winter, she added.

“The city needs to realize,” argued Luby, “that by opening shelters where people don’t go, (city leaders) are placing the shelters out of reach.”

Early January’s unseasonably warm temperatures were a reprieve for homeless people who often are vulnerable to hypothermia this time of year. But the season is far from over, and if December’s brief cold snap was any test, flaws in D.C.’s 2004-2005 hypothermia plan will leave many among the area’s growing number of homeless out in the cold this winter.

Since the official hypothermia season began Nov. 1, the city has declared 18 hypothermia days. These warnings are issued when temperatures fall below 32 degrees – when people living on the street risk frostbite, visual impairment and even death from cold temperatures. The most severe cold to date was experienced in late December when temperatures fell regionwide, reaching a low of 11 degrees with wind chills as low as 10 degrees below zero. Service providers at more than a dozen permanent, seasonal and overflow shelters reported increases in the number of homeless people seeking protection from the cold. Some sites such as La Casa Shelter in Ward 4, filled to capacity and set up extra cots to avoid turning people away.

Mary Ann Luby, outreach director at the Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless, said that two homeless men’s death in December, one found outdoors in an alley at the 1300 block of H Street, NE and one found on 16th Street in Silver Spring, Md., may have been caused by hypothermia, though no official findings have been released concerning the causes of death.

Ruth Walker, program director with the United Planning Organization (UPO), a nonprofit that runs the city’s hypothermia transportation program and hotline (1-800-535-7272), said that the hotline call volume is on the rise. In October, UPO fielded 800 calls from people seeking shelter from the cold. In December, that number rose to 1,227, and by early January the organization had handled 1,672 calls. These numbers are bigger than last year’s figures, said Walker, because the number of homeless in D.C. is increasing.

Workers at area shelters reported experiencing a host of small problems during the first cold snap this season, including a loss of heat and water at some sites. They also worried that a lack of transportation and uneven shelter locations will make this winter difficult for the city’s expanding homeless population.

Luby reported that the shelter in the 801 East Building at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Northeast lacked heat on one of the coldest days of the season, Dec. 20, and also cited continuing heat problems in the Crummel trailers at the New York Avenue site and the MLK trailers near St. Elizabeth’s. Other shelter workers noted that the women’s shelter that recently opened in D.C. General Hospital briefly lacked water in early December. However, outreach workers cautioned that homeless people will be facing even more fundamental issues this winter.

With the D.C. City Council’s vote (on Dec. 21) to close the Randall School Shelter, the city is committing itself to transporting people to other shelters,” Luby said. “The problem is that the city is taking vans that usually do or could do outreach and is giving them a transportation function, reducing outreach efforts.”

UPO has six vans available for night distribution of blankets and supplies and for bringing people to shelters, and two available for morning transportation. However, the same vans are used for both transportation and what Walker call “information services” — when drivers talk to homeless people, trying to convince them to seek shelter.

Chapman Todd, regional director for housing and support services with Catholic Charities, characterizes this kind of one-on-one, personal outreach as essential to building credibility and trust among the hardest-to-reach members of the homeless community who rarely frequent shelter and often are most vulnerable to hypothermia.

Yet the number of UPO vans has not increased in the past two years, even though the Metropolitan Council of Governments reported in June 2004 that the number of homeless people in the D.C. area increased in 2003 for the fourth consecutive year. While Walker maintains that UPO’s services will remain the same this winter and that the organization is committed both to transportation and information outreach, critics of the recent Randall closing argues that, by encouraging downtown homeless people to take vans to the 801 East shelter rather than accommodating them downtown, the city is placing even more pressure on scarce outreach resources.

Impractical and uneven shelter locations also squeeze resources, according to outreach workers. “There are more shelter beds available this winter than last year,” said Todd, “but the concern is where the beds are located. There are not enough downtown spaces.”

Marny Brady, director of advocacy and community building with Neighbors Consejo, the Ward 4 bilingual social service organization, provided a case in point. Sacred Heart, a 25-bed shelter in Ward 4, regularly fills up by 8 p.m. in the winter. People line up outside the shelter doors, Brady said, hoping for vans to take them to other shelters, often not fully aware of where those other shelters are located or unable to walk to those sites themselves. “It would be beneficial to have UPO focus on people on the streets, rather than on shuffling people between shelters,” she added.

Only one hypothermia shelter exists in Ward 3, a 10-bed site at St. Luke’s at Calvert and Wisconsin that just opened on Dec. 16. Other areas, such as Ward 7, have no shelters. Although Ward 1 in Northwest has a “huge, high concentration of homeless,” according to Brady, the ward has only 150-155 beds available for people seeking shelter from the cold, while wards 5, 6 and 8 each have more than 600 beds.

The increasing unevenness of shelter available is a major concern, said Luby. Many homeless people are unwilling to leave their neighborhoods and familiar surroundings, even to avoid frigid temperatures, she said. That problem is only compounded by an increase in the District’s homeless population that is far outpacing the resources available to reach and shelter people, even in the dead of winter, she added.

“The city needs to realize,” argued Luby, “that by opening shelters where people don’t go, (city leaders) are placing the shelters out of reach.”