Suspensions and expulsions in D.C. public and charter schools are disproportionately affecting homeless students, low-income students, Black students, and students with disabilities, according to a report from the Office of the State Superintendent of Education (OSSE).

“At-risk” students—students experiencing homelessness, enrolled in the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families or Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or under the care of the Child and Family Services Agency— make up 49.9 percent of all students in the enrolled population, yet they made up 84 percent of expulsions in the 2016-2017 school year.

In the same year, 645 students who were identified as homeless received at least one out-of-school suspension. Those students represent nine percent of all students receiving suspensions. The report showed that fewer homeless students received suspensions/expulsions in the 2016-2017 school year than in the previous year.

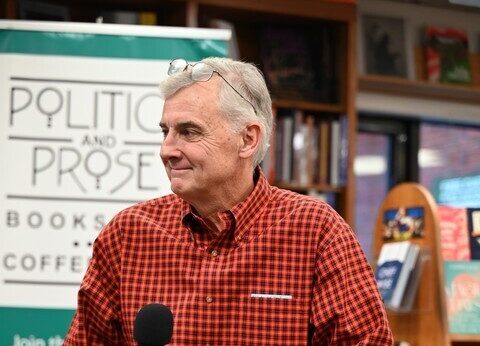

“Suspensions and expulsions often deprive students of their right to an education,” At-Large Councilmember David Grosso said in a press release. “Students pushed out of school are more likely to fail academically, to drop out, and to end up involved in the criminal justice system.”

Grosso, who chairs the committee on education, introduced his Student Fair Access to School Act of 2017 last November in an effort to keep students safe and in the classroom. The bill would limit suspensions in kindergarten through 8th grade to the most severe circumstances and ban suspensions or expulsions in high school for all minor offenses.

Grosso’s committee held a public hearing on Jan. 30 to discuss the bill. Jon Valant, an education policy researcher at the Brookings Institution, testified on the effects of implicit bias by school faculty members.

“There is reason to worry that well-intentioned, good-hearted educators do exhibit some form of bias. This can especially affect at-risk students,” Valant said. “At-risk and homeless students have to deal with a lot of challenges that other students don’t have to deal with. In a world where we’re punishing things like uniform violations, it can be very difficult for homeless students, and can really be out of their control.”

[Read more: Strict dress codes create educational barriers for homeless kids]

Valant explained that although some situations warrant suspensions or expulsions, in many cases these forms of discipline are overused and can begin to snowball for homeless students. Repeated suspensions or expulsions can affect the way a student is viewed by peers and teachers as well as how he or she views themselves.

“Perfectly good students can start to develop an image as a bad student,” Valant said. “It is the school’s responsibility to fight against that.”

Despite the comprehensive OSSE report, there is still a lack of data on homeless students in the district. This is, in part, because of underreporting. It can be hard to know whether a student is homeless if they do not self-report. Consequently, Valant says, much more research needs to be conducted on the challenges homeless students face.

“Education researchers often study how we can serve low-income students and students of color, but we haven’t spent enough time on homeless students,” Valant said. “That’s a problem because homeless students have very particular challenges that are different from virtually any other student in the school system, and until we really understand their challenges, I think we are behind in research.”

[Read more: This Virginia school counselor wrote a children’s book to help homeless students]

Jamila Larson, the executive director of Homeless Children’s Playtime Project, also testified at the Jan. 30 hearing. Playtime Project, which serves 650 children per year, provides children living in shelters and transitional housing sites with a place to play. At its four sites in D.C., the organization ensures that kids are receiving one-on-one attention, that social and emotional skills are fostered, and they are having fun.

Regarding exclusionary discipline, Larson said she rarely sees suspensions or expulsions as being beneficial for any students — especially homeless students.

“The consequences [of exclusionary discipline] can be more serious for students experiencing homelessness,” Larson said. “They have fewer natural networks of support, and the stakes are much higher for them in regard to the cradle-to-prison pipeline.”

The cradle-to-prison pipeline is a phrase used by advocates to illustrates how students of color and at-risk students are often pushed out of the education system and into the juvenile or criminal justice system. Taking students out of the classroom through suspension or expulsion can heighten the potential for apathy or delinquency because it forces the student to fall behind academically, making it less likely for him or her to reach graduation.

Illustration by Phillip Black Jr.

To prevent the overuse of suspensions and expulsions, schools must implement alternative disciplinary practices. Larson explained how some schools across the country use restorative justice practices to discipline students by having them acknowledge the harm they did and develop a strategy to repair it. In this way, the conflict can be resolved constructively without taking the student out of the classroom. Some schools offer one-on-one therapeutic support for students and train teachers on how to more effectively help students who are acting out. However, Larson pointed out, services like these require funding and resources to get implemented.

[Read more: Diversion program keeps kids out of prison and off the streets]

Grosso was quoted in the bill’s press release saying that he plans to increase funding for behavioral health staff in schools and professional development for faculty in the fiscal year 2019 budget.

“We know how negatively suspensions and expulsions affect the students pushed out of school,” Grosso said. “We need to change our approach to set every student up for academic success.”

The Student Fair Access to School Act of 2017 remains under D.C. Council review, and the Committee on Education will hold a series of Budget Oversight Hearings beginning on March 28.