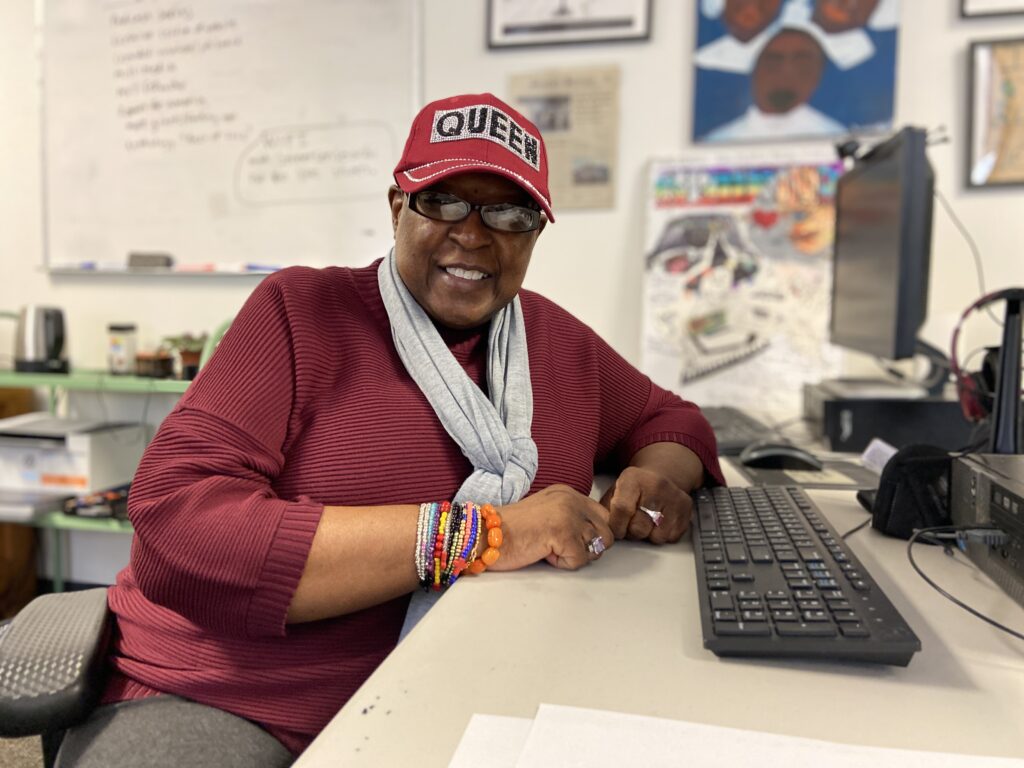

At the start of the pandemic, Street Sense Media artist and vendor Queenie Featherstone did not have a computer so she saw her doctor on her cell phone.

Featherstone, who also serves on the board of directors for Unity Health Care, was still able to see her primary care physician in person. But she had to use telehealth appointments in order to be referred to specialists for her other health care concerns.

“I’m not a computer genius so I did come here to Street Sense and I did ask case management to help me to connect because they’re more knowledgeable than I was at the time,” Featherstone said.

Even though her appointments have now returned to in-person care, telehealth remains an important way for many individuals to connect to physicians and other health care workers. However, this makes it difficult for D.C.’s most vulnerable citizens to meet their health needs.

“We simply are not able to spend the amount of time clients need in face-to-face services given the dangers of COVID,” Christy Repress said at The Committee on Health’s Performance Oversight Hearing on Jan. 24. Repress is the director at Pathways to Housing DC, a non-profit which connects people experiencing homelessness to housing and counseling services

“Telehealth is only a small piece of the solution,” she said. “The majority of our clients don’t have internet access or the technology they need to stay solely connected to providers in the virtual world. We have to continue face-to-face work, and we do.”

The expansion of telehealth services during the pandemic

Telehealth took off at the start of the pandemic when the Department of Health Care Finance authorized new rules permitting health care providers to be reimbursed for providing telehealth services to clients. Previously, providers could only be reimbursed for in-person care. So this legislation made widespread telehealth possible.

On March 12, 2020, DHCF adopted a rule permitting Medicaid to pay for telemedicine services delivered in a beneficiary’s home. On March 19, 2020, DHCF authorized payment for audio-only visits delivered via telephone.

“So it’s kind of a tale of both cities,” said Mark Levota, the executive director of the District of Columbia Behavioral Health Association. “There are new opportunities to use telehealth services that are pretty widely available in ways that they were not before the pandemic, but there are also major barriers for a number of D.C. residents to access those services.”

A significant number of behavioral health services shifted from in-person care to telehealth with the onset of the pandemic, he said. The majority of telehealth services in the D.C. Medicaid program are behavioral health services as opposed to medical health care.

How healthcare professionals respond to the rise of telehealth

Even before the pandemic, LeVota said, there was a shortage of behavioral health workers. Now, following almost two years of largely remote work, health care workers across multiple fields are experiencing burnout. Last year 42% of physicians reported feeling burnt out. This year the number was 47%. Many have left the workforce, leaving the remaining workers overworked, LeVota said.

Health care workers felt anxious heading into the pandemic, the clinical director of mental health rehabilitation services at Pathways to Housing, Kathleen Smith said. Smith oversees teams that serve unhoused people with mental health diagnoses. She is also a social worker who is certified to provide mental health services.

Employees at Pathways to Housing DC were especially worried because of how at-risk their clients were, Smith said. The majority of people experiencing homelessness in D.C. are Black men who are more vulnerable amid the pandemic, regardless of their housing status.

Many of Smith’s clients also have extensive care needs. They typically have a history of trauma, some have medical needs and some use substances.

“We would not be able to provide them care if we were not seeing them in person,” she said.

Health care workers and their families are also worried about coronavirus exposure in the workplace. Messaging about the safety of in person work seemed to change daily, Smith said.

“Those of us in health care … as well as people in our personal lives were really scared,” she said. “There was a lot of anxiety both for people personally, but also a lot of people had anxiety for our clients.”

In some respects, telehealth has been convenient for health care workers with concerns about working in person. Female physicians in particular have reported relying on the flexibility of remote work. They may need to work remotely because they have children at home as schools conduct virtual learning. But other health care workers have felt deterred by remote work.

“Further complicating the workforce shortage is the substantial shift in our health care delivery models over the past several years,” said Laquandra Nesbitt at the Committee on Health’s Performance Oversight Hearing on Feb. 23. Nesbitt is the director of the D.C. Department of Health.

“Telehealth…is the preferred model of service delivery for a lot of folks who offer health care,” she said. “So they’re no longer offering any in-person services, they’re 100% telehealth, we’re seeing that a lot.”

Some health care workers don’t like sitting in front of a Zoom screen or being on a phone seven or eight hours a day, LeVota said.

Like health care providers, patients may prefer telehealth for reasons of convenience or health concerns. In the case of students at D.C. public schools, the expansion of telehealth services is designed to make health care easier to access, said Andrea Broudreaux at the Committee on Health’s Performance Oversight Hearing on Feb. 23.

Broudreaux is a pediatric psychologist with Children’s School Services, CSS, an organization that works with D.C. Department of Health to provide public schools with nurses. CSS plans to expand their telehealth services next month, she said

“The new [telehealth] resource will minimize time off for students, minimize time off work for parents, provide additional support to in-school staff, improve management of chronic conditions, including behavioral health, allow for early recognition of injury, significantly increase access to pediatric specialists and improve health and educational outcomes at a minimal burden to the family, ” she said.

The challenge of foregoing in-person care

Still, some patients prefer or require in-person care. The issue comes when workers or patients do not have the option to choose whether to use remote or in-person care. Telehealth can be hard to access for non-English speaking patients, for example.

“Interpreters are not always able to conference into video platforms easily,” LeVota said. “Sometimes the instructions for how to use video platforms are not available for people who speak languages other than English, or they’re difficult even if they’re technically available.”

Hearing impairments can make in-person appointments preferable over video conferencing for similar reasons. Featherstone, who is hearing impaired, said that the volume on video conferencing is not loud enough for her to hear her doctors. She also had trouble navigating the technology.

“The first time I had to talk with the doctor over the internet or the video I got a little nervous,” she said. “I guess I wasn’t pushing the right buttons so I wasn’t able to see the doctor after several tries.”

If the option for closed captioning was available she wouldn’t have understood how to use it, she said.

Telehealth can also pose difficulties for people who have been historically disenfranchised by the health care system because it creates barriers to building trusting relationships with health care providers, Smith said. Race and gender disparities in health care make it hard for patients to trust their doctors and to receive adequate care. Especially in the case of patients with chronic illness, she said, doctors can undermine their patients’ pain which decreases the quality of care.

“I am a social worker, so I understand that a lot of this work is relational and depends on your relationships with people,” Smith said. Clients “have had medical providers dismiss them, imply it’s their fault they’re sick, ignore symptoms, so I do think telehealth can create a barrier to building a relationship where clients can establish trust with the provider.”

“It does matter that they trust the doctor and believe the doctor to hear them, support them and do good medicine for them,” she said.

And because many of her clients have difficulty using the technology necessary for telehealth services, they often sit with an employee who helps them to join meetings and share their screens.

Some of the gap in internet access was initially alleviated by devices provided to D.C. public school students, LeVota said. “They were allowed and encouraged to use those devices for school purposes but also for any of their health care needs.”

But now as D.C. public schools are no longer remote, and some schools have rules preventing students from transporting devices between school and home, it has become difficult for students to continue using devices as they had before, LeVota said.

How about telephone health services?

Telephone health services are potentially easier to access.

“For someone who may be unhoused but may have contact with a community support worker, it may be easier for them to send a text message to say ‘Hey meet me by the NOMA station at the McDonalds,’” LeVota said.

Lifeline phones have been another resource allowing people to access telehealth services, he said. They come with phone plans, and often data plans.

“I think a lot of people ended up getting Lifeline plans who met the eligibility criteria who might not have known they were eligible,” LeVota said. “I think a lot of good information has been provided to the community about that.”

But these phones are not a perfect solution either.

“It’s a pretty barebones phone package,” Smith said. According to her, they come with the issue that, if lost, users may have to pay to replace them. Many of her clients have trouble keeping a phone and most do not have internet.

“If they do access internet it is through data on their phone,” she said. “We also have clients who pretty frequently change numbers. We have clients whose phones are not set up to handle whatever web portal the doctors are using.”

There is an increasing agreement that not just cell phone access, but broadband internet for internet resources such as telehealth appointments, should be treated as a necessary utility such as water or electricity, LeVota said.

Barbra Bazron, the director of the Department of Behavioral Health, DBH, acknowledged the impact of the pandemic on health inequities, including telehealth access, in the Committee on Health Performance Oversight Hearing in January. DBH plans to provide devices to around 4,100 individuals for the purpose of telehealth access, she said. There is also a plan to open ten telehealth stations in community locations.

But even as telehealth expands, some patients will continue to need face-to-face care. Featherstone goes to see her doctor weekly or biweekly for her high blood pressure and diabetes. In her doctors’ offices, they are able to remove their masks so she can read lips and they can speak loudly.

“I’m just grateful that you can now go in person,” she said. “I still bring my hand sanitizer and I’m very mindful of the rules.”