As the last halfway house for men in D.C. prepares to close its doors on Oct. 31, many questions remain unanswered regarding the impact this will have on the community. The facility’s contracts with the Federal Bureau of Prisons that were set to expire in 2016 and 2017 were extended but not renewed following reports by the D.C. Corrections Information Council (CIC) and the Council for Court Excellence (CCE) that highlighted poor conditions and poor services at Hope Village.

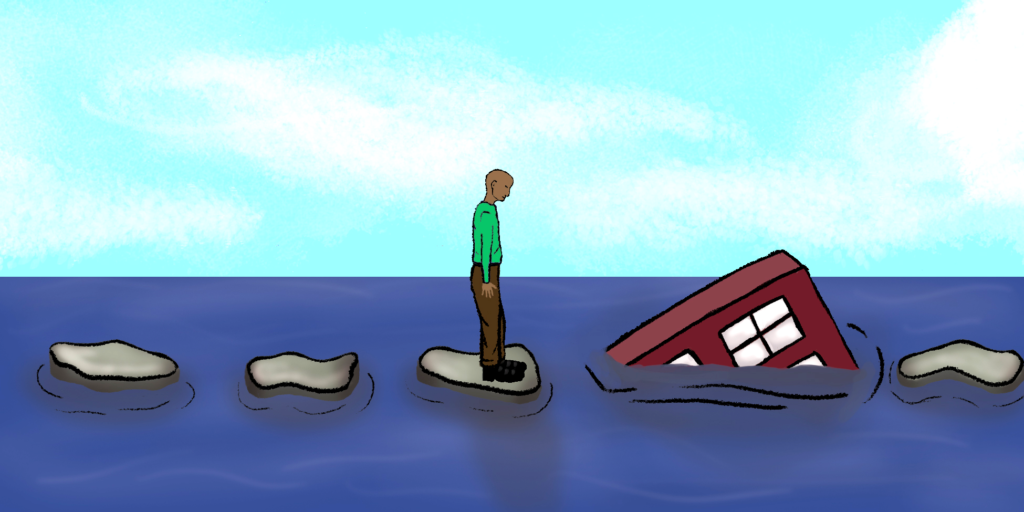

D.C. does not have a federal prison of its own, so those who are placed into federal custody can be sent to prisons as far away as California. This makes the role of a halfway house that much more important for incarcerated District residents who are returning home. With no plan in place to either renew Hope Village’s contract or construct another halfway house for men to replace it, men from the D.C. area may be sent to halfway houses in Baltimore or Delaware before returning to the District. Hope Village did not provide any additional information on the situation.

“It’d be like you have to re-enter twice,” said Tara Libert, the co-founder and executive director of the nonprofit Free Minds Book Club. “And it is critical that they begin reintegrating as fast as possible.”

Free Minds works with young inmates throughout their incarceration and reentry to provide mentoring and connections to supportive services.

Federally incarcerated citizens can become alienated when they are sent to prisons far away from the District. This alienation can lead to prisoners becoming disconnected from their communities and families. Halfway houses provide a bridge for these returning citizens to transition smoothly back into the community by helping them secure employment, receive services they need to reintegrate, and connections to past support systems. With just over 4,000 D.C. men in BOP federal custody as of September 2018, halfway houses play an essential role in the reintegration process as about half choose to finish out their sentences at one.

By closing down the only halfway house for men in the District, an additional step is created for returning citizens as they are sent to Baltimore and Delaware for reintegration. They may become further alienated from their community, families, and other support systems. In addition, connections or contacts they make during their stay would not be of much use in their return to D.C. after their stint at the halfway house is over.

“I think people don’t recognize the true impact that closing Hope Village has,” Libert said.

[Read more: “We’re all we got:” Former and current Hope Village residents fear the future of re-entry in DC]

The biggest obstacle that Libert pinpointed is the fact that these men will lose out on job opportunities and sources for potential jobs by being sent to a halfway house that is not in D.C. Employment is a big portion of the parole process and if they fail to be employed within a certain time, they violate the parole and get sent back to prison.

While Hope Village fills a critical need, the halfway house has been nicknamed “Hope-less Village,” by many former and current residents. Some prisoners have chosen to finish their sentences in federal prison rather than go through D.C.’s halfway house. This information is part of what prompted the CIC to do its first ever inspection of a facility in D.C.

During that inspection, current and former residents told the CIC that the halfway house lacked quality drug aftercare and substance abuse prevention programs. These were not the only services reported to be unhelpful. “Residents feel unprepared to complete basic life tasks, such as taking the Metro or bus and navigating their way around the District, along with more complex tasks such as housing, employment, and reentering a community they have been distanced from,” according to the 2013 CIC inspection report. There have been no subsequent inspections of Hope Village conducted by the CIC.

The Council of Court Excellence cited and reinforced the CIC’s findings in the 2016 report identifying challenges that all returning citizens face, not just those who were federally incarcerated. The lack of affordable housing, employment, and access to physical and mental care were challenges that were among the reports findings.

To address these challenges, the CCE gave recommendations to the District that would likely make the most significant impact. One such recommendation was not to renew Hope Village’s contract under the BOP. “Instead, it should use the updated statement of work to hold a new halfway house provider accountable for offering high-quality services,” according to the CCE’s report.

The nonprofit, CORE DC, had plans for a new halfway house in D.C. after it was awarded a federal contract by the BOP last year. Those plans were met with backlash by residents from the surrounding community and Hope Village, thus causing Douglas Development to back out of the lease with CORE DC for the property. There has not been any additional information given by CORE DC or the BOP regarding the situation.

“I felt like it would’ve been bad for me to go there.” said Davon Benton, a formerly incarcerated 23-year-old man who receives services from Free Minds. “I had only heard bad things about Hope Village. People would come back to the prison from there upset because they weren’t getting the help they needed. So when I was given the choice to go there, I said ‘no.’”

Benton said that when he was eventually released, without time spent in a halfway house working with a case manager and pursuing work opportunities, he struggled to connect with services that could help him get back on his feet.

“They told me that this place could help you with this and then this other one could help you with this other thing. Never did I get any directions of how to get these services, just where to go to.” Benton said. “And a lot of them just gave me the run around.”

According to the CCE report, agencies like the D.C. Mayor’s Office on Returning Citizen Affairs are unable to serve everyone who needs their assistance because of a lack of funding. Another recommendation in their 2016 report was to fully fund MORCA so that it could function as a hub for re-entry services rather than referring clients to resources scattered across the city. This would mitigate the confusion and frustration that Benton described.

“We can’t measure the emotional impact it takes on these men.” Libert said.

Benton partially credited his success to his will power and ability to achieve whatever he sets his mind to. “Even with this strong mindset though, I still needed help. Some people don’t have that mindset, so when they don’t receive the help, it’s easy for them to just quit.

“Free Minds gave me that direction and taught me how I could actually access these services. That was the biggest help to me,” Benton said.

“We need a halfway house here in D.C.,” said Rev. Graylan Hagler Hagler, who has been a prominent voice advocating for the construction of a new halfway house in the District and has been a longtime activist. “These halfway houses play such a critical role in returning home for these men.”