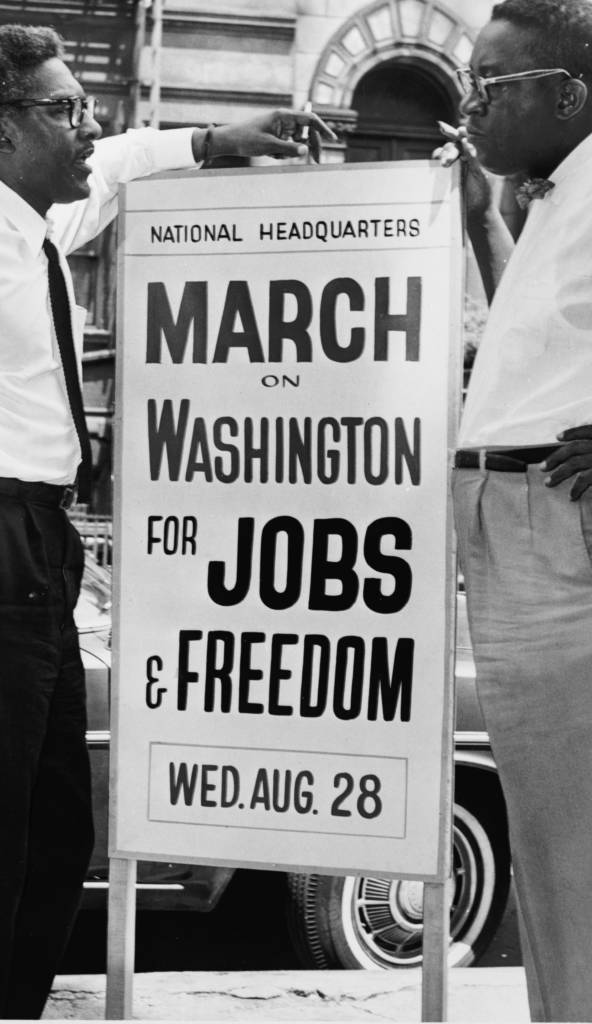

As Americans commemorate the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington our nation will reflect on Martin Luther King’s dream, a utopian vision that placed emphasis on one’s performance, not color. Many made the journey to relive this historic moment, envisioning what America was like fifty

years ago when Dr. King gave America’s version of the Sermon on the Mount.

Last weekend there were films of Birmingham and Selma along with countless interviews with those

who stood on the front line sharing compelling stories of freedom rides and Jim Crow. The event

signified a passing of the torch to the new voices of Black America, who will remind everyone that

while blacks have made great strides the struggle continues.

While many consider the March on Washington as the highwater mark of the Civil Rights Movement, not all truths have been disclosed. Were there others leaders who made an impact, besides Martin

Luther King and Malcolm X?

One was the actual architect of the March on Washington, Bayard Rustin. He learned peaceful

resistance in India, marching with Gandhi in that country’s struggle for independence. He taught

those tactics to a fiery militant named Mar- tin Luther King and the rest was history.

However, there are no holidays or posters for this great man because he was openly gay. The same civil rights establishment that condemned racism harbored bigotry to- wards homosexuals

and ostracized Rustin.

When planning began, the NAACP and Urban League threatened to call off the march for jobs and

justice if Rustin head- ed the march. However Rustin selflessly allowed A.Philip Randolph and Dr.

King to become the faces of the march and he faded from the spotlight.

Rustin passed away in 1987. Earlier this month, President Obama took an important step in giving

him a well-deserved place in history by posthumously awarding him the nation’s highest civilian

honor, the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

The President commemorated Rustin as “an unyielding activist for civil rights, dignity, and

equality for all.”

“As an openly gay African American,

Mr. Rustin stood at the intersection of several of the fights for equal rights,” the President

added in an official statement on the award.

But other tensions that ran beneath the surface in those days are less talked about. One of them was the suspicion with which many blacks viewed King and other civil rights leaders and groups. They feared that King and the others in the civil rights vanguard were part of a bourgeois class of blacks who were willing to sell out poor inner city blacks for the sake of their own financial and social advancement.

Some younger and angrier black organizers questioned the whole idea of moral persuasion. They saw

no logic in singing negro hymns while having bottles and rocks thrown at them in hopes that their

oppressors would be morally persuaded to give them rights that were granted ev- eryone else. They

viewed Dr. King’s mes- sage as vintage Uncle Tom and resented his high visibility. They wanted

complete liberation from white dominance.

Another overlooked aspect was the male chauvinism of the movement in those days.The male was the symbol of masculinity and leadership. Women were instructed to know their place and very few had leadership roles. Many were relegated to working as maids, secretaries and

laundresses. Some were subjected to sexual harassment.

While Martin Luther King’s dream instilled a liberal vision of what America could become, in the

end, the sixties were far from a golden age.