MBABANE, Swaziland – Jabulile Dlamini* is sweet sixteen and has never been kissed. And she is not expecting to be kissed any time soon or to even receive any gifts this Valentine’s Day.

While most of the girls in her class are excited about receiving presents from their boyfriends on February 14, Dlamini – who is HIV-positive – does not think she will get any.

She is reluctant to become involved in a relationship because of the complications her HIV-status will bring to it. But the secondary school student admits that she is not immune to love and is attracted to someone she goes to church with.

There is a spark in her eyes when she talks about her crush, a boy who has declared his love for her. However, the thought of having to disclose her status to him prevents her from declaring her true feelings.

“I’m worried that he might embarrass me by going around telling people about my status,” says Dlamini.

“I think it’s fair to disclose your status to your boyfriend but I’m not sure how he will take it,” she says. “Each time he proposes love I tell him that I can’t handle school and a boyfriend at the same time.”

But she admits that is not the real reason because most girls her age have already had their first kiss.

According to the National Emergency Response Council on HIV/AIDS, 15,000 Swazi children are estimated to be living with HIV/AIDS and a majority of these children were born with the virus. Antenatal surveillance at clinics in Swaziland shows an increase in HIV prevalence among pregnant women from 39.2 percent in 2006 to 42 percent in 2008.

Dlamini’s friends at school also do not know about her status because she is worried about the stigma and discrimination that remains rife in Swaziland. Swaziland has the world’s highest infection rate. Almost 26 percent of the population between the ages of 15 to 49 are HIV-positive.

Dlamini only discovered her status six years after her HIV-positive father died.

“I had always been a sickly child and my mother took me to traditional healers but my condition did not improve,” she says. “I had a bad rash all over my body and this affected my performance at school because I was absent most of the time.”

Her father, a mineworker, died in 2001. But Dlamini’s mother believed her husband’s death and daughter’s subsequent illness were the result of witchcraft.

Dlamini’s mother kept taking her to traditional healers until their relatives advised her to seek medical help.

In 2007 mother and daughter were referred to the Baylor College of Medicine Children’s Foundation-Swaziland (BCMCFS) for HIV counselling and testing.

Dlamini tested positive and her mother, a food vendor at Mbabane Market, was found to be HIV-positive as well. “When the doctor told me that I was infected with HIV, I cried and asked my mother where I got it. She said I was born with the virus,” says Dlamini.

She was only 13 at the time and was put on ART immediately. Thanks to extensive counselling and joining the Teen Club at BCMCFS (where she still gets ART for free), Dlamini was able to accept that ‘living with HIV is not a death sentence’.

Officially opened in 2006, the BCMCFS provides a safe haven for children and young adults living with HIV. A total of 1,500 children are currently part of BCMCFS where they are counselled and tested, initiated on treatment and introduced to a support group. Upon realising that a generation of children born with HIV had become teenagers, BCMCFS started the Teen Club.

About 200 teenagers across the country are part of the Teen Club with two sites in the commercial and administrative capitals of Swaziland. Two more sites are yet to be set up in other regions in the country.

“The earlier children are made to understand their status, the better they deal with HIV/AIDS,” says Dr Hailu Sarero, director of BCMCFS.

But dealing with these children is a big challenge for the BCMCFS because most of them are single or double orphans. Food security and dealing with abusive relatives are a bigger challenge, Sarero says.

“These are not easy issues and we partner with other organisations,” says Sarero. “As an organisa-tion, we can only do so much.”

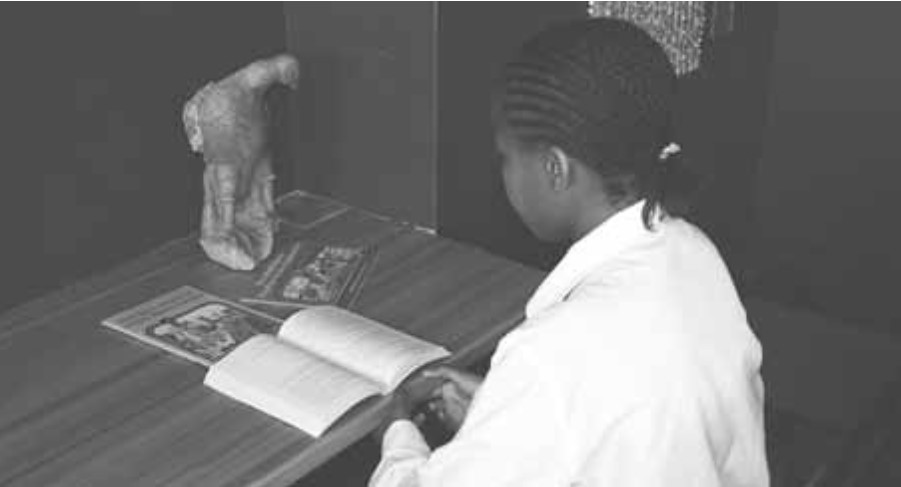

But for Dlamini, the organisation makes a big difference to her life. Once a month she meets with other teenagers living with HIV at the centre. Here adolescents living with the virus come together to talk about their concerns.

The club deals with a range of topics including how to take ARVs correctly; the pathology of the virus and how it is transmitted; dealing with disclosure to friends and peers; nutrition and HIV; and how to stay focused on one’s dreams.

*Name has been changed to protect the identity of the minor.

Courtesy of Inter Press Service.