Long-held criticism of the Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs — which manages everything from licensing plumbers and other professionals to enforcing housing safety codes and issuing building permits — led to a new law in April that promises reform by splitting the department into two new agencies.

Once funded and implemented, the law would pass responsibility for “construction compliance, rental housing safety, and residential property maintenance activities” on to a new Department of Buildings, and re-brand the remaining portion of DCRA as the Department of Licensing and Consumer Protection. Creating a second agency, the council says, is a way to streamline the process for issuing permits and conducting inspections, and to resolve concerns raised for years by tenant advocates and others.

But the future shape of the District’s regulatory apparatus remains unsettled — and the likely subject of legislative-executive wrangling over the fiscal year 2022 budget. The council passed the law in December over the repeated objections of Mayor Muriel Bowser, whose administration contends creating a second agency will add bureaucracy and stymie reform efforts already underway.

Since Bowser’s budget proposal does not include funding for the new agencies, it’s unclear whether these two new agencies will ever be established. Instead of funding for the new Department of Buildings, Bowser’s proposal recommended adding $16.9 million to DCRA’s operating budget, growing the agency’s total allocation to $90.6 million for FY 2022.

While the D.C. Council continues to review the city’s budget with the final votes scheduled in August, Bowser’s proposal highlights the continuing rift between the council and the mayor over what to do about DCRA. Council Chairman Phil Mendelson — who pushed the restructuring law through the legislative process after years of raising the issue — will have several opportunities in the coming weeks to propose budgetary shifts to fund the dual agencies.

Overriding a veto: No common ground on DCRA’s future

The Department of Buildings Establishment Act, which Mendelson introduced in 2018 and again in 2019 before final council passage in December 2020, is meant to address the agency’s long history of poor responsiveness and lax code enforcement.

Bowser, however, has actively opposed breaking up the nearly 40-year-old agency. She vetoed the bill in January, arguing in a letter addressed to Mendelson that it “wastes a significant amount of taxpayer dollars” and “duplicate[s] personnel and infrastructure already in place.”

The D.C. Council, however, voted unanimously in February to override the veto.

Mendelson, prior to the 12-0 vote in December, argued that DCRA has attempted many reforms over the years, none of which have succeeded in making the agency truly effective. (Councilmember Brandon Todd recused himself from voting.)

“Its permit center, unveiled in 1983 as a ‘one-stop shop’ to make obtaining a permit seamless, became such a headache for homeowners and developers that they often paid surrogates to stand in line and do the paperwork for them,” Mendelson said.

These problems, he argued, have persisted well into today.

At a council hearing in December 2019, DCRA Director Ernest Chrappah acknowledged the agency’s past problems but emphasized in his written testimony that his team is making progress.

“Too often, residents would contact the agency about an issue and never hear back about how and if it was resolved. And if a customer called to follow-up on their request, they would need to re-explain all the details,” Chrappah said.

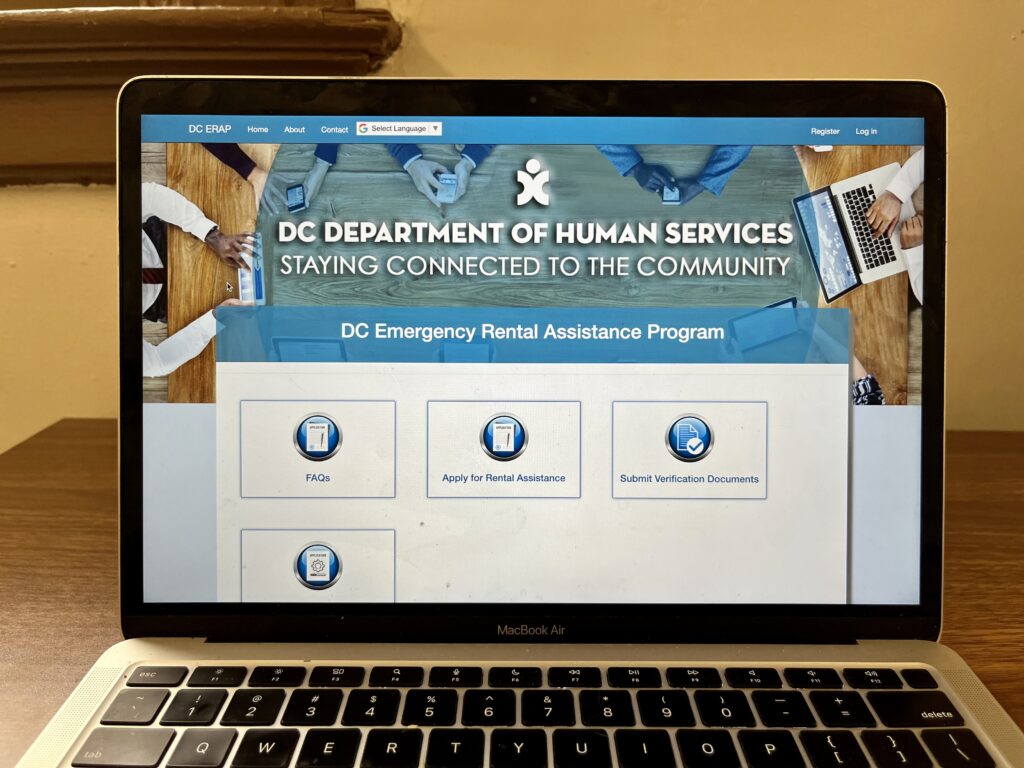

According to Chrappah, however, DCRA’s new data management tracking system has streamlined this process and “ensures that issues are being dealt with promptly.”

A recent query on the agency’s online performance dashboard from June 22 shows that 14% of DCRA customers rate their experience as “poor” compared to 17% who state their experience has been “satisfactory.” The other 69% of customers rated their experience as “excellent.”

The dashboard also shows the agency meeting more of its targets for building inspections, licensing, and permitting than it did in 2018.

Chrappah cited these statistics in his public testimony at a budget hearing in early June, touting them as yet another sign of the improvements the agency has made.

“I want to thank Mayor Bowser for the increased investment in DCRA, which I view as a down payment on the future of an agency that by any objective measure is steadily improving,” he said.

But not all agree that these metrics show actual progress.

Some advances are due in part to a program implemented in 2019 that allows residents to become inspectors after a few days of training. Likened to online services like Uber, the resident inspectors serve as on-demand quasi professionals who are paid anywhere between $30 and $100 per inspection.

Kathy Zeisel — an attorney and advocate at the Children’s Law Center, a nonprofit that advocated for the establishment of a Department of Buildings — said in an interview that a person who has “a few Saturdays of training” may not be the best judge of whether “your home is structurally safe and healthy for you.”

Zeisel, whose clients have included tenants who couldn’t get the agency to fix unsafe living conditions, also cited inherent conflicts of interest among DCRA’s components as another main reason to split up the expansive agency.

“DCRA’s main customers are developers. They fast-track permits if you spend over $1 million. One of their main jobs is to make sure development goes safely and smoothly,” Zeisel said.

According to Zeisel, this function inherently conflicts with another of DCRA’s primary duties: fining businesses for code violations.

In FY 2020, DCRA issued $10 million in fines for housing violations but collected only about $70,000, according to the agency’s online data dashboard. For Zeisel, the paltry collection rate is one manifestation of the conflicts of interest within DCRA.

For many, DCRA’s problems are rooted in their own experiences with the agency.

Testifying on behalf of her neighbors on the 400 block of Shepherd Street NW, resident Kisha Salters said during the June 10 hearing that she’s been trying for years to get DCRA to do something about vacant, rat-infested houses in the area. She described the properties as “crumbling” and overrun with mold, and said they had been like this for almost as long as she can remember.

“I’m now 46 [years old] and some of these homes have been boarded up since I was in my 20s,” Salters said.

Salters also said she sees DCRA as falling short in fulfilling its responsibilities to the public.

“All they do is slap a couple of different color signs on the doors. .. I’m not even sure why DCRA even exists,” Salters said.

Testing the limits of a legislature’s ability to force change

Like Bowser, John Guggenmos — a Ward 2 advisory neighborhood commissioner with 31 years of experience owning and operating businesses in D.C. — thinks DCRA has made “massive” progress in recent years.

While Guggenmos describes these changes as “astronomical,” he also says he’s wary of creating another bureaucracy in order to change a fundamentally bureaucratic problem.

“If the D.C. Council could write a bill that would be detailed enough to tell a bureaucracy how to run its agency, then we wouldn’t be here — they would have already done it,” Guggenmos said.

In her January veto letter, Bowser argued that breaking up DCRA would only slow down the improvements that supporters such as Guggenmos say the agency has been making.

Bowser also argued that the bill overstepped the council’s authority, stating that a portion of the law that directs the mayor to appoint several key officials “with the advice and consent of the Council” violates the separation of powers established by the Home Rule Act. The positions involved include the zoning administrator, a chief enforcement official, and a strategic enforcement administrator.

While it remains to be seen whether the mayor is ultimately able to stop the plans to break up DCRA, it is likely that the council will try to identify the funding for it, and pressure Bowser to implement the law.

Evan Cash, the committee and legislative director for the Committee of the Whole, said that he expects Mendelson to find the appropriate monies for it.

“The chairman has previously indicated that he would like to find the funding for it,” Cash said over the phone.

The first opportunity to do so came Thursday afternoon, when the Committee of the Whole — which Mendelson heads — marked up the budget for DCRA and other agencies under its purview. Although the committee was unable to identify funding to break up the agency, Mendelson will be working with the council’s budget office to reconcile the recommendations of various committees and come up with a final budget proposal to present to the full legislature.

Mendelson reiterated his commitment to creating the new Department of Buildings in a tweet Thursday: “We couldn’t find the funding in Committee of the Whole (COW) agency budgets but we will look for funding when the full budget comes before the Council in the coming weeks.”

We couldn't find the funding in Committee of the Whole (COW) agency budgets but we will look for funding when the full budget comes before the Council in the coming weeks. https://t.co/4ZRIldjPVU

— Phil Mendelson (@ChmnMendelson) July 1, 2021

The fiscal impact statement issued by the city’s chief financial officer in December, when the council voted on the DCRA legislation, says that funding the new Department of Buildings would require an extra $11.7 million in FY 2022 and $33.1 million over four years.

This article was co-published with The DC Line.

Will Schick covers DC government and public affairs through a partnership between Street Sense Media and The DC Line. Year one of this joint position was made possible by the Poynter-Koch Media and Journalism Fellowship, The Nash Foundation, and individual contributors.

UPDATE (07.01.2021)

This article has been updated to include that no funding was identified to implement the Department of Buildings Establishment Act during the Committee of the Whole’s July 1 budget markup session, which occurred after publication.