Troubles at home send many Washington, D.C. children and young adults into foster care or the juvenile justice system. From those unsteady places, it is easy to get caught in a downward spiral of mental illness, social isolation and uninformed decisions that eventually leads to chronic homelessness.

The fracturing of a young life can start out as a conflict with parents, neglect, abuse or the loss of the family home. Many children struggle with their parents over their sense of identity. Some young people who come out as homosexual find themselves disowned or even kicked out of their homes. Girls may be sexually abused by stepfathers or molested by their mothers’ boyfriends.

Many troubled youth come from low- income families and neighborhoods known for crime and drugs. Some have parents who are too young to be parents themselves. Others have inherited poverty from their grandparents’ generation.

For these young people, the possibilities of growing up healthy, enjoying respect and obtaining a quality education can be very remote. Any dreams they may start out with can be crushed, and they become different people.

“I was now cold and angry, a high school dropout, violent and pugnacious. I had given up on any dream I’d had of becoming something beautiful, something great,” said J.W., a 19-year- old woman quoted in an at-risk youth survey report “From the Streets to Stability: A study of youth homelessness in District of Columbia” by the D.C. Alliance of Youth Advocates. J.W. said she was raped and molested by her stepfather for four years starting at age 14, and she was kicked out of his house at 18.

The survey report, written by Margaret Riden of DCAYA, reported that of nearly 500 unaccompanied young people between the ages of 12 and 24 who completed the survey last year, 330 were literally homeless on the night prior to the completion of the survey. The remainder of them were considered to be at high risk of homelessness or unstably housed.

The report found that even before the recession hit, an average of 1,400 chil- dren received welfare services in the District.

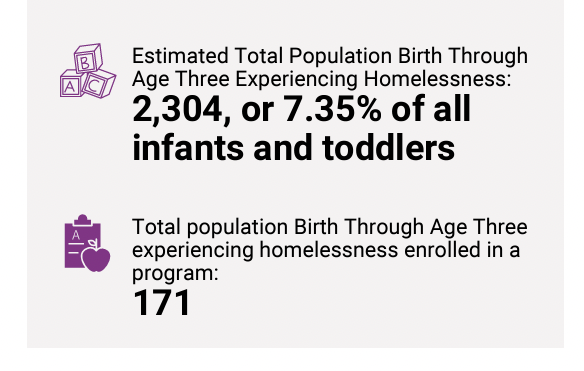

Accurate data about youth homelessness is hard to find, but a 2011 count of homeless people in the Washington region, conducted by the Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments Homeless Services and Planning Committee found 3,249 homeless children in the city and its suburbs. The figure did not include unaccompanied youth.

Deborah Shore, founder of Sasha Bruce Youthwork, a nonprofit for young people from unstable families, said that there is an enormous diversity of how young people across the country become runaways or homeless. “There is, however, a strong link between poverty and how the young people become vulnerable,” she said.

Shore said that many of the organization’s clients experience many disruptions in their family lives. They have a hard time concentrating in school. Sometimes they are socially isolated. Other times, their hardships make street life seem attractive. “We’ve seen many young people who see violence in the family, who have abuse visited upon them, and [are] also very angry, that sometimes they are lashing out,” Shore said.

D.C. has its own entrenched patterns of need and vulnerability, Riden said. “It has generations of abject poverty. In D.C., it’s a little more acute, because there’s a massive white-black split. Geo- graphically, the district is very defined,” she added, with more affluent areas concentrated in the northwestern part of the city, and poverty more prevalent east of the Anacostia River.

DCAYA’s survey finds that about 39 percent of the nearly 500 youths questioned were “system involved,” meaning that they had once been in foster care or the juvenile system. Children in the government’s foster care system also often face a bleak future in spite of the care that they receive. Children who age out of the foster care system often deal with an unstable transitional program.

It is difficult for vulnerable young people to become independent after foster care if they have been uprooted from their familiar environment and sent 90 miles away from home, or if they have been moved around, or if they have run away up to 10 times. Many do not finish high school or hold a General Education Diploma. Most do not possess any soft skills to get into the workforce. Some lack adequate emotional development.

Foster placements may be far away from the child’s familiar environment and can disrupt normal development.

“I firmly believe that keeping kids in their communities, with tons of wrap- around support, is the way to go,” Riden said. The first option for foster care providers should be members of the extended family, whether an uncle or a grandmother, she said. The kin- ship care subsidy, however, has been cut, making providing care harder for grandmothers, aunts and uncles who act as parents for children.

Riden said that the foster care system needs to be better integrated. As it is, she believes, only very savvy young adults are able to flourish once they age out. She would like to see a transitional center that would provide a kind of “one-stop shopping” center for young people preparing to leave the system. “If I’m 18 or 19 and struggling with a place to live every night,” she said, “I don’t have the energy to go to eight different places to get the support that I need.”

In Riden’s mind, such a center would be staffed by case managers who would understand the young adults’ needs and be a consistent presences in their lives, and providing a bridge to link them with mentors within the larger community.

Sasha Bruce Youthwork has an independent living program that helps its young clients meet their needs to eventually live a healthy, independent life. The organization provides counselors, emergency shelters, houses, financial management training and parenting training for young parents. The web- site, sashabruce.org, has success stories about some of their clients entering college and getting good jobs. The organization runs 60 units of housing, which Shore says is not enough: There is a long list of young people who have applied for their service. “We have a waiting list pages long, and after the economic crisis, there has been an explosion of needs,” Shore said. She wishes that more people would care about the situation and help the children and the young adults.

Both Riden and Shore agree that a successful system will help break the cycle, because otherwise it will be very difficult for D.C.’s troubled young adults to build a stable family, thus creating another generation of vulnerable young people. “People should care about this,” Shore said. “How many more jails can we build? How many more terrible circumstances where people are so stressed that they do terrible things? We can stop that, we can make a difference. Lives can change, and there’s so much hope.”

Riden said that hope also comes from the young people themselves. “They are really resilient young people,” she said, “who know they have to put in the work to be successful, and they’re generally willing to do it if they feel supported.”