Jerome Johnson, who has lived at the L Street NE underpass for three years, said he was told he should receive housing through a D.C. pilot program. But as of Sept. 28, he is instead being removed from his home on Monday.

In the summer, Johnson says Pathways to Housing D.C. assured him he was “on the list” for housing. But he was later told this would not be the case. Now he and some of his neighbors from the underpass are being advised by their case managers to move to a park at New Jersey Avenue NW and O Street NW to stay connected with Pathways.

“It’s funny, but [the Pathways employee] can’t give me a reason why I was neglected,” Johnson said. “He doesn’t have an answer.”

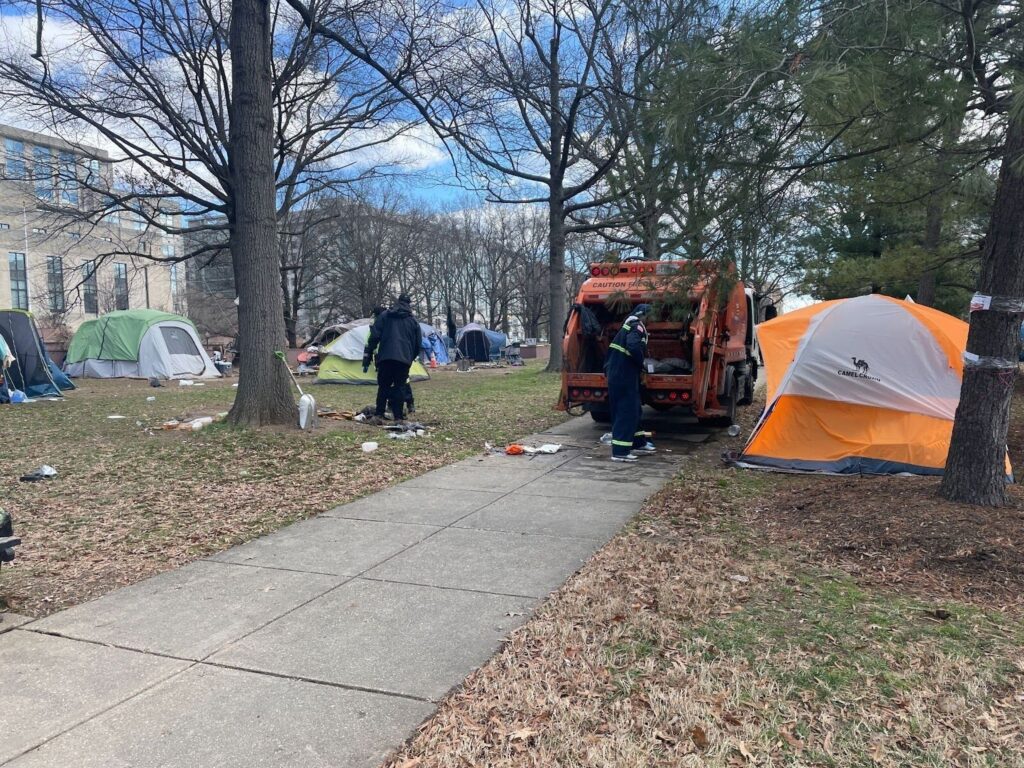

The Coordinated Assistance and Resources for Encampments (CARE) pilot program will permanently close three longstanding encampments, but the city says it will provide temporary housing to all residents as they are forced to move. The sites include the two underpasses at L Street NE and M Street NE, the park at New Jersey and O where Johnson plans to relocate and an encampment in Foggy Bottom along E Street NW across from State Department offices in the old Red Cross building.

During a Sept. 22 community meeting convened by several ANC commissioners, Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services Wayne Turnage said the locations were chosen because they are three of the largest encampments in the District. Through the pilot program, the District will fund one-year leases for residents.

After the NoMa underpasses are cleared — currently slated for Oct. 4 — they will become “pedestrian passageways,” according to posted notices. All property blocking the sidewalk will be subject to immediate removal and disposal. The District used the same designation when it shut down the K Street NE encampment in January 2020, which is just a block away from the L Street NE encampment.

The people living at New Jersey and O will be removed no later than Nov. 4, when the park will be closed for renovations. There is no closure date set for the E Street encampment as of yet.

Jamal Weldon, encampment response program manager, said during the Sept. 22 meeting that a closure date for E Street will be announced if the risk factors “meet the same standards” as the NoMa and New Jersey and O encampments. The D.C. government has to work with the National Park Service about the E Street property because they share jurisdiction there.

Typically, unhoused residents remain in their living situations, such as encampments or shelters, while seeking assistance.

Encampment residents that were forced to leave a triangle park in Mt. Vernon Square over the summer told Street Sense Media it is difficult to do everything needed to apply for housing assistance within several months. Some had been working through the process for years.

With this new program, the District’s goal is to keep residents in temporary housing, Weldon said during the Sept. 22 meeting. Meanwhile, the city will provide services to help them secure a housing funding source such as permanent supportive housing (PSH), targeted affordable housing (TAH) or rapid rehousing (RRH).

Encampment residents won’t receive a one-year lease if they did not sign DMHHS’s “by-name list” by Aug. 23 to show they were an encampment, Turnage said. This document was assembled through 90 days of canvassing plus data gathered via engagement across the last three years, Weldon added. He said encampment residents who are not on the list may still be eligible for other housing resources.

Some attendees mentioned in the virtual meeting’s chat window that they were supportive of the measure. One who spoke, Gene SirLouis, said they wanted D.C. to expand the program throughout the city.

“What I’m hearing and reading in the chats are reasons why this won’t work. But nobody’s got any better solution, so I very clearly want you to go ahead with this trial,” said SirLouis. “It’s the only way we’re going to know if it works.”

But unhoused individuals, housing advocates, and people who previously experienced homelessness questioned Turnage during the meeting about what would happen to the individuals who don’t receive housing.

Georgia Pearce, who was unhoused for 10 years, said they aren’t criticizing the District for housing some of the residents but for closing the camps.

Turnage pushed back, saying he didn’t think the D.C. government should apologize for its actions.

“If we were shutting down the encampments, notwithstanding their contribution to public safety and health issues, without telling folks who are living there that we’re going to put you into housing, I think all the criticism would be justified. But that’s not what we’re doing,” Turnage said.

The meeting was tense at times. Nikki Del Casale, a volunteer with a local outreach group, questioned Turnage.

“We talked to some of the residents today. And some of them said they were either too young, or there were other factors that made them not match with housing. So what are we going to do about those people? Are we assuming they’re looking somewhere else?” Del Casale said.

The program did not encounter anybody that is not eligible for housing due to age, Turnage countered.

“They might not be eligible for PSH. Then we pay for it out of local funding,” Turnage said. “But we’ve not encountered anybody that’s not eligible based on some immutable characteristic, or any other factors.”

Del Casale asked Turnage about residents who said they were denied housing, regardless of the reason. “Just answer the question.”

“First of all, I don’t work for you. I’m a public servant. I don’t need you to talk to me like that,” Turnage said. “I’m not on trial. So you don’t have to tell me, ‘Just answer the question.’ That’s offensive. We are on this [virtual meeting] to answer questions. Give us time, don’t instruct us. We are doing the best we can. If this is going to be a productive meeting, you can’t talk to us like a criminal.”

Turnage said no one is being denied housing or being forced into housing. But the residents who don’t receive housing or who declined the pilot program offer will ultimately be barred from the encampment locations.

ANC 2A01 Representative Yannik Omictin, who moderated the Sept. 22 meeting, asked why the “accelerated housing” and pedestrian passageway components are both being included in the program. Turnage explained that they believe these encampments present public safety and health concerns.

“We are in the middle of a pandemic. Many of the encampment residents are not vaccinated,” Turnage said. “We understand that when you live every day outside and just tending to the basic needs of a human being creates challenges when you are living in a public encampment.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends allowing people living in encampments to remain where they are.

“Clearing encampments can cause people to disperse throughout the community and break connections with service providers. This increases the potential for infectious disease spread,” CDC guidance says.

Residents who don’t receive housing like Johnson, or who decline the pilot offer, will have to move. Those who do not receive housing through the pilot program are strongly encouraged to connect with outreach groups to receive case management services, according to an FAQ document from D.C.

Aaron Howe, a Ph.D. student in philosophy at American University and founder of the mutual aid group Remora House, said they’re worried about the people who “fall through the cracks” and lose connections to outreach groups.

In addition to Remora House, Pathways to Housing D.C. also shared concerns for those not receiving housing. Pathways has regularly been out to the encampments, ensuring people get the necessary resources, said Executive Director Christy Respress.

“Our CARE team has been working furiously over the past couple of weeks to help match people to an apartment of their choosing that meets their needs, their hopes, and their dreams,” Respress said. “It is hard to make a perfect by-name list in a geographic area because some people stay and are very fixed there, and others might come in and out. That is one of the challenges and lessons learned that we need to talk through with the city.”

The NoMa clean-up day was rescheduled twice to allow more individuals to move into housing, which Respress said has started slowly.

Clyde, who did not give his last name, has been staying in the encampment for about a year and will receive housing through the program. He was born and raised in the District.

“Some people got apartments, but a lot of people were left out. They’re trying to see what they’re going to do with the people that were left out. Some are putting them in hotels, but unfortunately, right now they haven’t done that,” Clyde said.

He said he hopes these apartments will be nice and that the mayor can continue to create housing programs such as the pilot program. He expected to move into his new apartment this week.

“I think everyone who lives in D.C. should not be homeless,” Clyde said.

Respress explained that she is excited for this program to get underway because of the housing opportunity. The organization will continue to work with everyone who did not make the list.

“As you can imagine I actually can’t share any details about a specific person’s case due to privacy laws,” Respress said in an email from Street Sense Media inquiring into Johnson’s situation. “We will continue to work with every single person who is not on the main list to create a housing plan. It doesn’t mean that the person isn’t eligible for other housing resources- including PSH, RRH, targeted affordable housing, etc.”

The program has obtained apartments throughout the D.C. area wherever there are vacancies or available units. Pathways had an active list of more than 100 apartments that were available as of Sept. 23, Respress said. The organization continues to work with landlords to ensure individuals have a choice of where they live.

Last month, the Office of the Chief Financial Officer counted 17,614 vacant apartments in the District. In January, the city counted 5,111 people experiencing homelessness.

“With the influx of federal and local resources that we will see in the next few months, and in this coming year, we will be ending chronic homelessness if we do this. And we have to do this right because this is people’s lives,” Respress said.