“There was a gentleman here this morning who, for whatever reason, had determined that I was a sorcerer and that I was trying to kill him,” Beau Stiles said to about ten people cramped in a small room one Wednesday morning in September.

Computers lined the walls, all of them in use. But at the sound of Stiles’s voice, everyone pulled up a chair and turned to hear what he had to say.

Stiles is the program coordinator for Georgetown Ministry Center. He leads a community meeting like this one every week for the center’s guests.

“First and foremost I assure you all: that was not the case. I was not trying to kill anyone,” Stiles went on.

He proceeded to explain how the gentleman called the police, who came down to the homeless drop-in center to question Stiles and heard the man’s story.

“They opted not to charge me with sorcery, which is a good thing,” Stiles said. “And he left.”

His story was met with laughter, but ultimately there is a lesson to be learned.

Stiles has no hard feelings towards the man. The situation exemplifies a common problem for outreach centers: how to provide services to individuals experiencing homelessness who also have a mental disorder.

Gunther Stern, executive director of Georgetown Ministry Center for the past 25 years, identified the biggest challenge he faces with one word: Anosognosia.

“It is a syndrome associated with neurological disorders. About half of people with mental illness also have some degree of Anosognosia, which is the inability to understand that they have a problem,” said Stern. “So they might be yelling and howling at the wind but they don’t perceive that they have a mental illness.”

This issue becomes especially deadly during hypothermia season, the period between November and March when temperatures regularly drop below 30 degrees Fahrenheit and endanger the lives of those living on the streets. The D.C. Interagency Council on Homelessness approved it’s Winter Plan in September, which outlines how to best help people experiencing homelessness during this time. The 2015-16 plan includes a significant expansion of street outreach.

In order to best help people with a mental illness that refuse help during hypothermia season, there is a process called FD-12 that can be invoked to get them to safety.

“If a person is exhibiting signs and symptoms of a mental illness and they are placing themselves in danger, there are police officers, mental health professionals, and a variety of people that have been trained to make that assessment,” said Dr. Tanya Royster, Director of the Department of Behavioral Health. “Then they can forcibly, involuntarily remove the person and get them to a safe situation.”

Royster stressed the importance of evaluating people to make sure they are indeed experiencing metal illness. Free will is a right, and the government can’t take that away without thorough examination.

There is an ethical line drawn between forcing people to accept help and respecting their decisions as people with free will.

“And that is hard for us, because we want to take care of everybody,” Royster said. “But in the end, people have some choice if they are mentally able to do so.”

As a way to help people get off the street faster, District government has embraced the Housing First model. This form of permanent supportive housing is based on the concept that, first and foremost, an individual or family should obtain stable housing before they can properly address other issues such as addiction or unemployment.

Stern emphasized that Housing First is a tool and not the end-all solution to homelessness. People are going to be left on the street even after Housing First has been adopted universally, according to Stern.

“The people that I work with are mostly missed by [Housing First] for two different reasons,” Stern said. “One is that they don’t get hit because they are too low functioning. Or the second is that they are too low functioning that they are unsuccessful once they receive housing.”

He believes that half the people out there won’t be served by Housing First because they will refuse service.

“There’s a woman, Janice, at the bottom of the street here who stays in the same place and every time I see her and ask her if she is interested in housing she says ‘I’ve got two houses,’” Stern said. “She sleeps by the bank. And she shits and pees where she sleeps. There is not much I can do.”

Stern and the Georgetown Ministry Center offer the homeless community services such as showers and laundry facilities, case management assistance, access to the Internet, phones, and medical care.

Staff members, usually accompanied by medical staff, will regularly go on outreach runs to extend a helping hand to the homeless community and provide them with a friendly face and medical assistance. On a rainy Wednesday afternoon I accompanied Stern and nurse practitioner Devora Winkfield on one of these walks through the streets of northwest D.C. looking for people who might need healthcare.

Medical professionals look for symptoms such as severe swelling, sores, or respiratory difficulties during these outreach runs, according to Winkfield.

Stern lead everyone around the area, stopping in locations where he knows people will be. Almost everyone we encountered knew him by name.

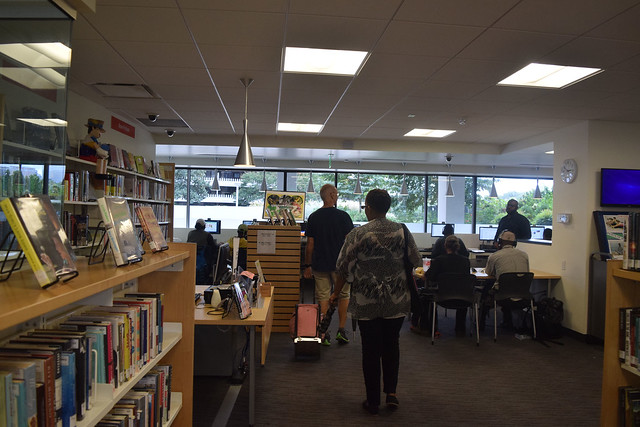

The group made a brief stop at the West End Interim Library where Stern checked in to see if anyone needs help.

“The library is probably the biggest day center in the country for homeless people,” he said.

Just around the corner from the Foggy Bottom Metro station, Stern and Winkfield asked a gentleman sitting on a bench whether he needed any help. While he initially refused, after a few minutes he decided to let Winkfield take his blood pressure. It was very high.

Stern and Winkfield then discovered that the man is on medication and they advised him on how to take it, which he had been doing incorrectly. “Same time everyday, preferably with water and after a meal,” Winkfield told him. There is hope that he will heed their advice.

“We have to change the way we look at people with mental illness who decide to live on the street, and actually intervene whether they want us to or not,” Stern said. “I have been talking to the same people for 25 years. People do occasionally move up. But most of the people I talk to are still there. Or they’ve died.”

There is no easy solution. People are difficult to engage in treatment, especially if they mistrust the system that is there to help them or if they deal with mental health issues, according to Tanya Royster.

“So we know that there are a lot of people out there that we can continue to serve, but we could always do more,” Royster said. “Everyone could always do more.”

Beau Stiles ended his opening statement at the Georgetown Ministry Community meeting by asking everyone to be sympathetic to those with a mental disorder.

“It’s important to remember that we all have different perceptions,” Stiles said. “When you encounter that type of behavior, just be conscious that one—its probably not personal and two—its very real to them. And be sensitive to that.”