Tim moved under the K Street Bridge on Nov. 29 after U.S. Park Police discovered him in Rock Creek Park and informed him that he could not continue camping there.

“Common sense when you’re living out here tells you to find someplace that’s a windbreak, find someplace that covers you from wet. The logical place is under a bridge,” he said, explaining why he chose the new location. “Other than that, you’ve gotta look for a doorway, and very few of those are deep enough to provide any real cover, let alone a windbreak.”

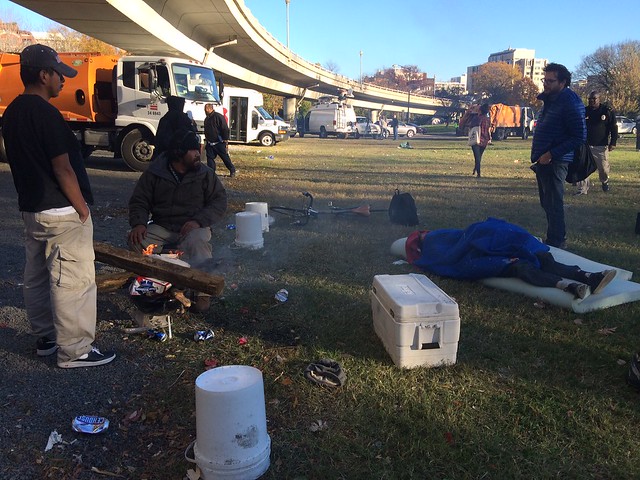

A week before Tim set up his home under the bridge, that area experienced a sweep from Department of Public Works (DPW). On Nov. 20, sanitation trucks gobbled up tents, mattresses, camp chairs and bags at “Camp Watergate,” a patch of land under the Whitehurst Freeway, just down Rock Creek Parkway from the Kennedy Center and across Virginia Avenue from the Watergate complex, where more than 40 men and women had been living in tents.

“You are devils, you are devils, you are devils!” one man yelled at DPW employees as they loaded a couple of grocery carts into the trucks to be crushed.

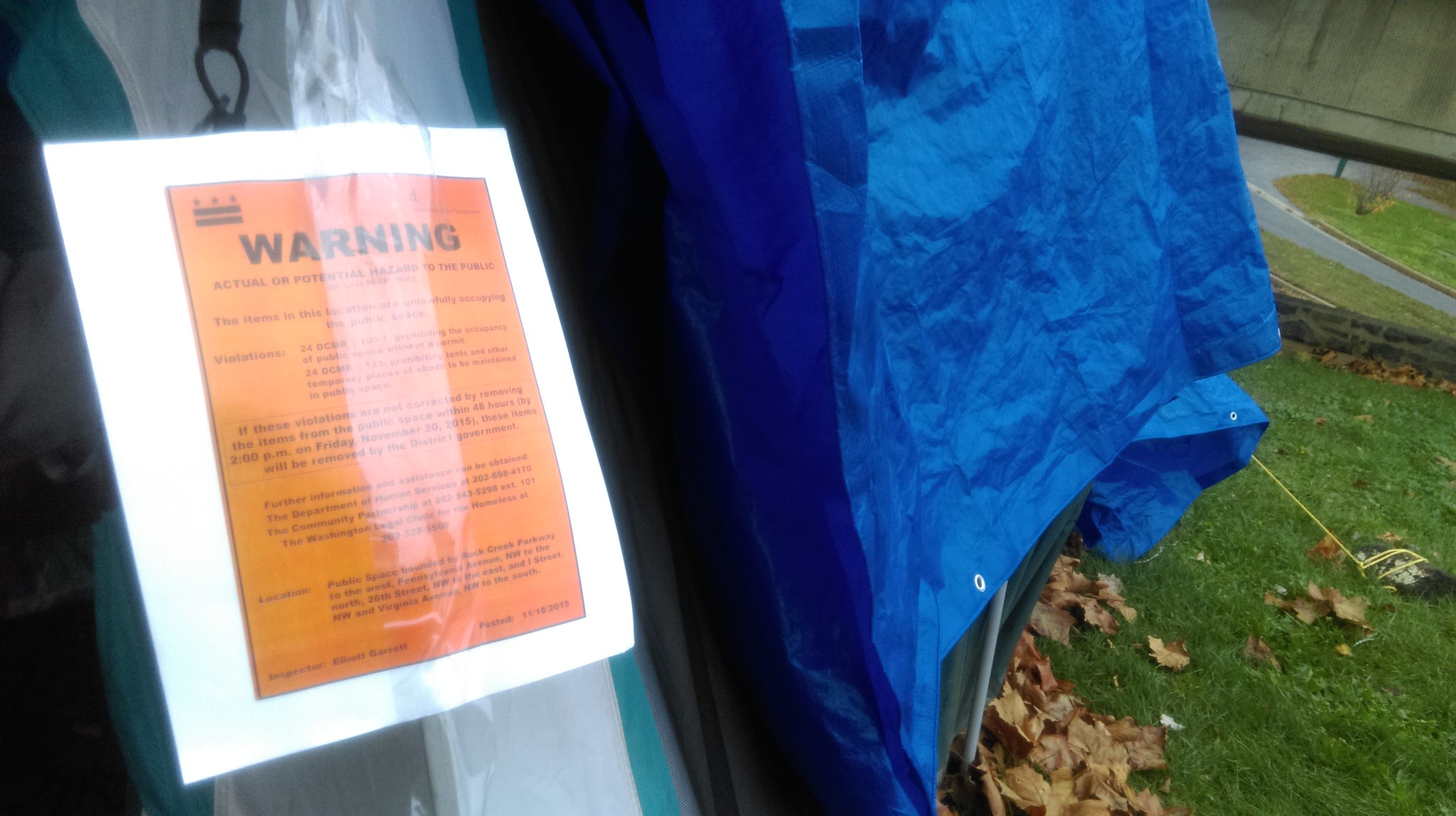

Tim returned to his tent the next day, Nov. 30, to find a waterproof orange notice telling him that by unlawfully occupying public space, he created an “actual or potential hazard to the public.” The orange notice stated that Tim’s belongings would be removed by the District if he did not move them himself before 2 p.m. on Dec. 2.

When that deadline arrived, Tim and the other campers learned their eviction was postponed until Dec. 3. “I really don’t know what they expect,” Tim said. “They’re not giving us any alternatives. They’re saying you’ve gotta be out of here, but not suggesting any other place to go, other than the usual ‘have you tried the shelters?’” He was very clear on why shelters are unacceptable to him: in addition to being infested with bedbugs, shelters are hot spots for theft, disease, and violence.

“If someone wants to prey on you they know exactly where you are. At least when you’re out on the street, you have a little wiggle room to not have your stuff stolen,” Tim said. “Obviously, I understand [why people want the campers to move]: if you own property you don’t really want a homeless shelter where you reside.”

The second sweep of that area in two weeks happened Dec. 3. Waterproof notices similar to what Tim had received had been posted in many locations around the main encampment, including several satellite tent-clusters such as under the K Street Bridge, to inform residents of the cleanup. “Eviction…cleanup, call it what you will,” Tim mused.

The First Sweep

The Nov. 20 cleanup was first attempted on Monday, Nov. 16. As required by District law, the general cleanup notices were posted more than 14 days in advance. It was widely reported in media coverage of the cleanups that these notices informed campers to vacate the area by the posted date: Nov. 12. But most neighborhood residents, housed and unhoused, believed that only trash and debris would be targeted for cleanup. Not people.

When Foggy Bottom Association (FBA) President Marina Streznewski saw the DDOT notices, she called the office of Brenda Donald, Deputy Mayor of Health and Human Services (DMHHS). It was Streznewski’s understanding that city protocol during hypothermia season in the District — Nov. 1 to March 31 — is to leave in place tents, blankets or anything else that can keep people warm during that time. The DMHHS office confirmed to Streznewski that the cleanup would remove only trash.

Nevertheless, on Friday, Nov. 13, Department of Human Services (DHS) and Department of Behavioral Health (DBH) outreach workers spent the day informing campers that they would have to move before Monday, Street Sense first reported, and assessing them for potential housing placement.

It seemed to Streznewski that “the deputy mayor had done an about-face.”

“There are a huge range of opinions about homelessness in our community,” Streznewski told Street Sense. “I had one person say ‘I pay too much in taxes to have to look at this.” On the other hand, people have said ‘they are our neighbors too.’”

The FBA has been trying to reconcile these viewpoints and get all members working toward tangible solutions. Six months ago, the association created a task force specifically to address ending homelessness in Foggy Bottom.

“We want to actually solve problems, not just move them to somebody else’s neighborhood,” Streznewski explained. “These people are living here for the same reasons we are: it’s a safe community, convenient for transit and close to healthcare.”

Installing public trash cans located near encampments is one initiative the task force had begun working on. And at the November ANC 2A meeting, a resolution to seek a solution to the toilet problem was submitted by the People for Fairness Coalition and approved by the FBA.

“We’re trying to figure out the toilet issue. Porta-potties can get expensive for the long term, so we want to look for another solution,” Streznewski said. “Obviously, we don’t have the resources that the government does, but we can achieve little things. We’ve received quite a bit of support from DHS, the mayor’s office and the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD). They’ve been great about answering questions – what’s against the law, what’s not, etc. We’re trying to be helpful.”

Around 10 a.m. Monday, November 16, a sanitation truck arrived and several tents across K Street from the main encampment were taken down. However, DPW workers at the main camp only raked and picked up trash. Several homeless campers pitched in and worked alongside them.

In an email to Street Sense that morning, Jenna Cevasco, spokeswoman for Deputy Mayor Donald, wrote that “there have been complaints from the neighborhood about this site for many years” and cited “the increase in debris and tents in recent weeks” as reasons for the cleanup’s immediacy.

Indeed, Google Street View images show that the number of people sleeping at the camp grew significantly in recent weeks. Images from months prior showed only a handful of tents, which weren’t widely available to the campers until Arnold Harvey, a Waste Management employee from Maryland, began giving them away through his charity, God’s Connection Transition.

On Monday, November 16, outreach workers arrived with a shelter transport van to remind people that they had to leave and encourage them to seek shelter. Some campers left the area but most stood their ground. Only two people got into the van that day: a couple from Georgia who had been promised transportation assistance to return home with their two dogs.

Deputy Mayor Donald accompanied the van and spoke with several individuals in an attempt to convince them to enter a shelter. “Our concern is of course that [living in the campsite] is not healthy, not sanitary, and it is illegal,” Donald told WUSA9.

No timeline, memo or speech was given to residents regarding the camp’s fate. City workers, including the supervisor on site, were expressly forbidden from speaking to the press. At times there were more news crews on-site than outreach teams. The MPD officers that arrived shortly after the sanitation truck were the only city employees that would readily answer questions about their own presence. The officers said they weren’t there to move people—or to make a statement on anyone’s behalf, they were quick to point out—only to keep the peace. DHS and DBH continued to speak with campers. No one seemed to know how to proceed, city workers included. Everyone waited.

Watergate Encampment Update: No one was asked to leave. MPD officer on scene reports this is not DC land. pic.twitter.com/yqQb5DVbPK

— Eric Falquero (@EricFalquero) November 16, 2015

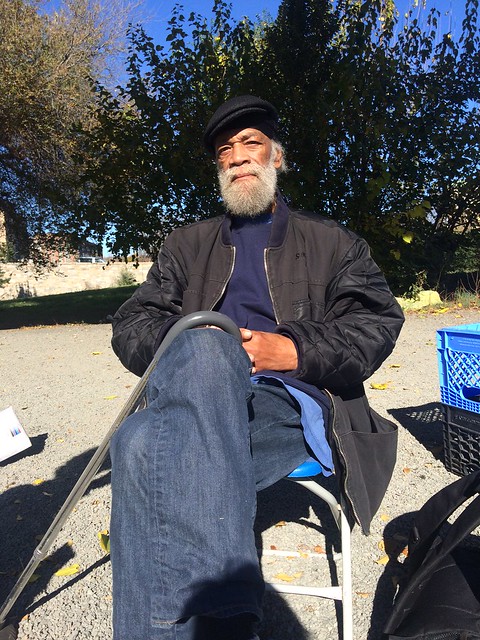

The rumor mill churned: everyone was getting apartments before anyone was evicted; this was happening on federal land and D.C. didn’t have jurisdiction to move anybody; if someone’s tent was touched against their will, they could file assault charges. All three of those statements are false, but were believed true at one time or another on Monday, November 16. Minutes from a meeting that afternoon state that the D.C. Interagency Council on Homelessness (ICH) Outreach Policy/Protocol working group identified that there is an “issue with mixed messaging. Not clear to outreach teams and/or individuals residing in encampments whether tents are being removed by DPW or individuals are going to be ticketed and/or otherwise limited in their ability to access the area. Need clarity on whether tents are life-saving articles that will not be removed during Hypothermia season.” The standoff on Monday, November 16, resumed Tuesday morning. Some campers skipped their routine of breakfast at nearby nonprofit Miriam’s Kitchen for fear that city workers would swoop in while they were gone and dispose of tents and other supplies. 65-year-old Owen, who has been homeless for 14 years, was so stressed by the prospect of another displacement that he had to be checked into GW Hospital. Because there is no law against sleeping in public, only against doing so within a temporary abode, some campers packed up their tents and slept in the open in anticipation of the cleanup.

“It’s like trying to sleep next to a wrecking ball, and you don’t know when it’s going to drop,” described John, a camp resident. Clarity came on Wednesday, November 18, when 48-hour eviction notices were posted around the camp. The next morning, shelter vans arrived to take twelve campers to view apartments. “Word is, they’re coming by with keys for everyone,” a woman named Stefanie, John’s wife, said while DHS workers called off names from the list. That morning it seemed even more people had arrived after word got out about the apartment tours the previous day. New faces intermingled with those who had been on-site since Monday. The rumor that the plan was to house people, rather than merely shelter them, was generating hope and expectations. When Friday came, no one had moved into housing, but the campers’ 48 hours were up. Notices of infraction were being distributed and personal effects were being put into storage or destroyed – depending on the items’ perceived value and each individual’s level of cooperation.

Advocate Diana Pillsbury complained that even though Deputy Mayor Donald claimed translation services were available during this process, nothing was provided in writing for the at-least six Hispanic men who had been living there longer than anyone else. Pillsbury provided verbal translation on the spot. Several of the men expressed frustration. “Maybe one of the most heartbreaking things about today was all the government workers who told me they didn’t want to do it, they were under orders,” Pillsbury tweeted Friday. By the end of the sweep, only a handful of the 20-25 tents remained under Whitehurst Freeway. A fence was installed on Saturday in the field where the camp had stood, not interfering with those who remained under the freeway.

DHS and police put up a fence yesterday. But “it’s just for publicity” say campers. #campwatergate pic.twitter.com/SYmF61nKF9 — Alex Zielinski (@alex_zee) November 22, 2015

The fenced-off area will be used to facilitate cleanup and inspection for a portion of the sewer system adjacent to the Kennedy Center, according to John Lisle, a spokesman for DC Water. This maintenance has been needed since February and must occur before March 31, 2016. Permitting for the project began in October before initial DDOT camp cleanup notices were posted. It is linked to a stormwater backup in May 2014 that caused sewage to overflow on the National Crescent Trail. No construction or digging will occur at the Camp Watergate site. It will be used as a staging area for physical work and equipment storage in relation to the Kennedy Center maintenance.

“I think they could find another staging area,” said Miriam’s Kitchen Advocacy Specialist Jesse Rabinowitz in disbelief, when he learned the project details.

That was sweep number one, which did not bring an end to the mixed messages and general lack of information provided to campers and community members alike.

Media inquiries regarding the camp were required to flow through the deputy mayor’s office. Street Sense’s questions regarding shelter conditions, whether or not tents should be confiscated during hypothermia season, and if/when other city encampments would be handled similarly, went unanswered.

“You can read into it how you want,” said Tim, referring to the lack of transparency.

Political Will

Advocates for the homeless have criticized the encampment cleanups and have contacted the D.C. Council and the Bowser administration requesting, among other things, that the District “follow the encampment protocol created by the Deputy Mayor, including the provision that prohibits the removal of life saving materials including blankets and tents.”

Until now, the Bowser administration has been predominantly lauded by the advocacy community for approving a data and community-driven five-year plan to end homelessness in the District and investing an unprecedented amount of funds in homeless services for FY2016.

Councilmember At-Large David Grosso visited Camp Watergate during the Friday sweep, and was the only council member to visit the encampment during the three-week process.

Grosso told Street Sense he first noticed tents along Interstate 395 and elsewhere more than a year ago. A staff member he sent to check on the campers reported that they needed a lot of services, but they were clean; they had said very clearly that they would like to move into a better situation but in the meantime, they felt much safer in their camp than in shelters.

“So we never raised it, I never sent a letter,” Grosso said. “The Gray administration kind of let it fly and didn’t do anything. But for some reason Brenda Donald, over the past couple months, has decided that these [encampments] are unacceptable. Partly, I think people don’t like seeing them. It’s kinda good if you ask me. I want people to see people living on the street. We should raise some alarms and put up neon signs that say ‘look at the failure of our society.’”

The council first heard about the cleanup after Deputy Mayor Donald’s visit on the afternoon of Monday, November 16, according to Grosso.

Video by Jonas Schau

Like the advocates who have written-in about the camp closure, Grosso asked Deputy Mayor Donald to not do a blanket closure of encampments across the city. However, at the Mayor-Council Breakfast on Tuesday, November 24, encampment closures were discussed briefly between the mayor’s debrief on implementation of the DC General family shelter’s closing and a report on Mayor Bowser’s recent business trip to China.

“Our intent is there will be no more new tents,” said Mayor Bowser. Deputy Mayor Donald promised to continue outreach in an effort to convince campers to “move on.”

Ward 2 Councilmember Jack Evans suggested fencing the entire area off. His communications director, Tom Lipinski, told Street Sense that Evans’ office has been contacted over a hundred times about the encampment, but not all comments have been complaints.

“The comments have ranged from neighbors coming up to Councilmember Evans at a restaurant to relate that individuals have defecated in their lawns,” said Lipinski, “to concerns for the well-being of the individuals living in these tents.”

Councilmember Evans was unavailable to be interviewed but provided a statement: “Homelessness and a lack of affordable and safe shelter housing continue to be very real problems for many people in the District. We know that it becomes more difficult to provide the critical wraparound services to individuals who are not in shelters or permanent supportive housing, and it’s my understanding that many of the people living in this encampment are chronically homeless. I support the work the Mayor and the Interagency Council on Homelessness are doing to try to provide services for these individuals. On a larger scale, the city is working quickly to identify and create shelters across the city to provide vital services to those in our community that need them the most.”

Gunther Stern, executive director of Georgetown Ministry Center, has been providing street outreach in the surrounding community for 25 years. “I came here in 1990. There’s always been a thriving community here,” said Stern, who is approaching retirement. “[The city] keeps responding with solutions that cost a lot of money to keep people out. That could be better spent to house people.”

Over the years Stern has seen walls erected to block off under-bridge areas, spaces welded shut to further enclose those areas, and now fencing rented from a Maryland branch of SONCO Worldwide, which was added around the DC Water fencing after a second eviction on took place on Thursday, December 3.

Despite seeing folks living in the shadow of the freeway consistently for the past 13 years, Stern confirmed that the population drastically increased after the tents began to be donated. “It was [only] the Hispanic community until maybe six months ago. [The number of campers] grew 10 to 20 times after that.”

Where to Go

God’s Transition Connection founder Arnold Harvey told The Washington Post that he began distributing the tents throughout D.C. and Maryland because they helped people staying outside keep themselves and their belongings safer, sleep better, and get noticed so that they could receive help.

The encampment sweeps have been an entirely different sort of attention for homeless campers. Ironically, “the Hispanic community” is who remains camping under the freeway on-ramp today. Though at least one man, Ramiro, has been told he will be taken to look at an apartment this week. Another man said on December 2 that he had been told a group of six men would receive placement in a house together.

By 2:15pm the next day, everything was gone. The six men sat together on a knoll overlooking Camp Watergate with nothing left but a tarp and several bags. “There is no house,” the same man said. “We all need housing.”

They weren’t the only ones.

Paul, a veteran of the U.S. Navy who has been camping in the area since experiencing family trouble in July, had been elsewhere applying for a job when the sanitation trucks arrived. He saw one truck over the hill as he returned, but by the time he got to his tent, everything had been disposed of.

“I don’t even have a sleeping bag. I don’t even have a change of damn clothes,” Paul said an hour after the cleanup occurred as he panhandled on K Street. “This is what I’m left with: a radio with dead batteries and no antenna. That’ll keep me warm at night.”

City officials say they’ve been working hard for months to connect with campers, but Paul slipped through the cracks and had not spoken with a single outreach worker by December 3. He blames staying on the move during the day, not loitering at the camp.

“I saw them putting up the notices. The understanding I had [from other campers] was that we had an extension until we found placement,” Paul said. “But I guess they wanted to speed the process up or something.”

The day of the sweep, Paul echoed the shelter complaints of other campers. “What I’m worried about now is how I’m going to stay warm tonight. I can’t go to a homeless shelter because I like to sleep. I don’t want to have to sleep with one eye open. I’ll sleep out in the cold.”

He has since obtained another tent, and is safeguarding its location.

Twenty-five of the estimated 40 campers that were evicted were targeted for housing (though not actually housed yet) through DHS and DBH’s assessments; this is progress, since they probably will be housed in the near future. There’s simply not enough housing available.

In the two weeks between the first and second sweep, 10 people from the camp had been housed, and one other had been matched to a successfully inspected apartment and was awaiting move-in.

Stefanie and John have been housed. Tim has not. Paul, the military veteran, has not. Housing was found for a woman named Karissa and her cousin James. They were awaiting city workers to help move their belongings as the second sweep wrapped up.

“Me and my cousin stood our grounds. And let them know man, we can’t go to shelter, so you gotta place us somewhere,” Karissa said. “If it’s not somewhere, help us get a permit for a tent.” She described how comfortable sleeping on the bare carpet of their new apartment had been the night before. Now she’s looking for a school to enroll in.

“GED is a must for me,” she said with a smile. “If I can’t find a school, I’m trying to find me a job.”

It came to light at a December 1 quarterly meeting of the Interagency Council on Homelessness that most of these housing placements have occurred “outside of protocol.” That means that people were housed independently of their score in a “coordinated entry” system that determines how vulnerable and in-need of housing someone is compared with the rest of those in need.

“I’m worried the city is housing the most visible rather than the most vulnerable,” Jesse Rabinowitz told Street Sense.

While some advocates and city officials have criticized this disregard for coordinated entry, Staff Attorney Ann Marie Staudenmaier of the Washington Legal Clinic for the homeless thinks it is a moot point.

“The coordinated entry system is important, but when people are literally living outside because they have nowhere safe to stay indoors, we believe they also deserve priority for housing placements,” Staudenmaier told Street Sense. “D.C. has more than adequate housing funds available this year to house both groups of people. It just needs to utilize those funds more efficiently.”

Despite these disagreements, advocates and people experiencing homelessness concur that for the immediate future, in lieu of housing or safe and secure shelters, people should be allowed to stay in their tents.

“It’s really hard for me, not being an expert in it, to know whether someone is safe or not when it gets cold out,” said Councilmember Grosso. “But I think we could probably take our cue from folks who live on the street.”

A camp resident who wished to remain anonymous stressed that campers look out for each other. “All the homeless people here know each other. Maybe not the name, but the face. I know that guy, and he knows that woman over there. So we all recognize and watch out for each other.”

A December 10 letter sent to the mayor and D.C. Council from the People for Fairness Coalition echoed these sentiments. “Many live in encampments because it is the only place where they feel safe and supported and can keep their belongings safe. Unlike the random strangers they would encounter in a shelter, they have formed a true community of people who know and watch out for each other.”

“Nobody owes me anything out here. And I don’t expect anything. But the tent, I really would have liked to have that, man. When the wind starts blowing, it gets cold,” said Paul. “And once you get a chill on your bones… you ever see these guys walking around in layers and think to yourself ‘man it’s hot out, how does he have all that stuff on?’ He’s just now getting the chill off his bones from 3 o’clock in the morning.”

A closed meeting was held Friday, December 11 between advocates and city officials, including Deputy Mayor Donald, to discuss improving how encampment evictions are handled. For now, continued cleanups are still expected.

Anyone who would like to claim their property should call Community Bridge, Inc to arrange for next-day delivery: 202-483-9339 – regardless of the location or permanence of your address.

Landlords can contact the D.C. Department of Human Services at 202-671-4446 to participate in housing programs.

Olivia Aldridge, JC Diaz, Roberta Haber, Dottie Kramer, Jonas Schau and Alex Zielinski contributed to this report