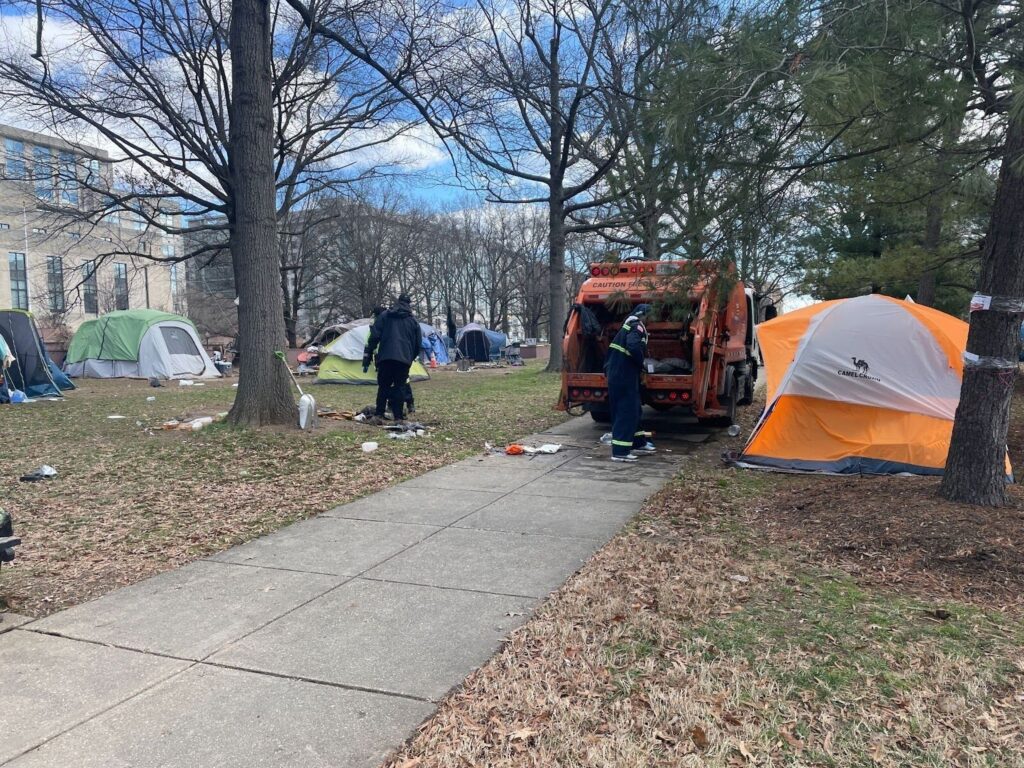

A series of encampment cleanups took place on Sept. 27 between First and 2nd streets near the NoMa-Gallaudet U Metro station in Northeast Washington. The first cleanup occurred at an underpass at the intersection of 2nd Street and K Street. The process then moved to L Street, then M Street, and concluded at First Street.

Prior to the 10 a.m. start time, people residing in the area scrambled to gather their belongings and relocate them outside of the cleanup zone.

Dennis, who had set up his tent at the underpass between 2nd Street and K Street after his apartment was destroyed, only arrived three days before the scheduled cleanup.

“I had my own place and my whole ceiling caved in so I had to come here. Stuff got damaged and this was the only stuff I could save,” he said, pointing to six large trash bags filled with his belongings and a green tent. “It’s hard. It’s really frustrating.”

He’s waiting on the city to fix the apartment.

“They’re taking forever and it’s so frustrating,” Dennis said.

He was disappointed by the lack of notice given by the city to those living in the affected area. He hadn’t seen the signs or heard anything from his neighbors on the street.

“They didn’t give me enough time to move my shit. I can’t move all this stuff by myself,” Dennis said. He started to cry and pointed to his left hand, on which he wore a black brace.“I got a broken hand! It hurts. My wife won’t even help me move, you know? I had to send my kids away because I don’t want them seeing their stuff get thrown out.”

A representative from the Office of the Deputy Mayor of Health and Human Services patrolled the cleanup along with government outreach workers, a Metropolitan Police Department officer and Department of Public Works employees.

Clean NoMa, a division of the NoMa Business Improvement District funded by NoMa residents within a specific 35-block radius and an independently contracted cleaning service worked around the city crews to clean the sidewalks after the encampment were removed.

According to a spokesperson for the deputy mayor’s office, there is no official partnership or memo of understanding between the inter-agency encampment removal effort and the NoMa BID, which contracts these extra services for the neighborhood and schedules them around the city’s work.

For the past two months, this specific area has experienced encampment cleanups every two weeks, Aug. 14 and 30, Sept. 13 and 27. The deputy mayor’s office anticipates another cleanup on Oct. 11.

It is illegal to live in a “temporary abode” on public property in the District, such as a tent, car or trailer. Shortly after Mayor Muriel Bowser instituted stricter enforcement of this regulation during her first year in office, a detailed update to the city’s encampment protocol was put in place to guide the process.

[Read more: Bowser’s first attempt to tighten encapment enforcement ended in a three-week standoff]

City officials posted signs around the area — on street lamps, on walls next to tents — to provide at least two week’s notice that a cleanup would occur. Since the area has been re-cleaned so frequently in recent months, the signs have not been taken down, new dates are simply taped over the old ones.

Another man forced to evacuate from the K Street underpass had experienced previous encampment cleanups at the site and planned to return to the same spot after the cleaning finished.

“I got my couch and my [moving cart] and I’m coming right back here when this is done. I’ve already done the same thing twice,” he said. But the couch was discarded by the city.

From the perspective of the deputy mayor’s office, the couch was large and rather soiled. Egress and cleanliness are priorities for public space. “This is not our response to homelessness. The cleanup itself is an acute health and safety response,” said Sean Barry, the communications director for the Office of the Deputy Mayor of Health and Human Services. “Outreach is an important component so we can move these people into strategies that are working for individuals and families. But it’s not overnight, it’s an ongoing conversation.”

Residents of the First Street encampment next to Union Station shared a different view of city outreach efforts during an Aug. 14 NoMa cleanup.

“It’s just harassment,” said Ms. Bobbie, 66, who has lived in that area for four years. She said the only option she has ever been presented with is shelter (“not an option”) and nothing has changed through all the cleanups and outreach efforts she has experienced.

Ms. Bobbie’s neighbor, Monica, echoed these sentiments. She and her husband have been homeless since their building — The Lynnhill Condominiums in Temple Heights, MD — was condemned. “It’s the first time I’ve been on the street and I’m exhausted, it’s just overwhelming,” Monica said. “This is our fifth tent. I’m missing work right now so that I can be here and keep them from throwing away my stuff.”

Monica views outreach workers as nosy. She cited her experience waiting for almost a year after giving her personal information to someone who had said they could help her obtain a new ID, with no results. “They claim they want to help you but they just want to know your information and that’s it. They don’t want to help you with nothing,” she said. Her old ID and Social Security card were discarded during an encampment sweep.

The city’s encampment protocol specifically outlines that important papers and priceless items such as family photos are not to be discarded. But individual accounts vary and a pending class action lawsuit on behalf of homeless District residents alleges that people’s property is being improperly thrown away.

[Read more: The first cleanup at Union Station occurred in March of 2016]

The city’s policy also entitles camp residents to storage bins that may be used to save belongings for up to 60 days. However, unless storage is specifically requested, the bins are stored in a government vehicle at the cleanup site, according to the deputy mayor’s office. City workers are tasked with verbally letting people know they can ask for storage.

“I don’t expect sympathy from people,” Ms. Bobbie said. “People don’t want you to feel sorry for them. They just want a place to live so they can get a job. Mayor Bowser has this plan for building nice new shelters. Why not build nice new affordable apartments?”

A homeless encampment cleanup was conducted at Union Station from approximately 11am until noon.

At least 11 homeless residents were temporarily displaced. Most planned to return immediately.

3 trash trucks, 2 police vehicles & 1 DC government-branded minivan were utilized. pic.twitter.com/RJU3aU93je

— Street Sense Media (@streetsensedc) August 14, 2018

Eric Falquero contributed reporting.