On a clear morning, Nov. 2, a homeless man was restrained by several Metropolitan Police Officers and arrested for simple assault after he jumped between an officer and a tent, and smacked the officer’s hand when she tried to open the tent. MPD officers were assisting the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Health and Human Services with a Homeless Outreach Clean-Up Project, according to the police report.

The rest of the encampment cleanup appeared much calmer. The strip of E Street NW that sits between 20th and 21st Streets has a niche use. It is highly trafficked by State Department employees that work in the former Red Cross headquarters and a mix of college students and tourists that ride a steady flow of “International Limousine Service” and “A La Carte” shuttle buses that drop off at the center of the block.

The presence of trash trucks, police cars and pickup trucks used to block the street drew attention from passersby. Police tape surrounded the tents that a dozen people had been living in on the tree-lined south side of the street. A small group of George Washington University students had turned out to protest the eviction of homeless people from public land, but they too gave way to arrest warnings. The students stuck around to help campers pack up their belongings.

“They put a police line up and said ‘step behind the line or you’ll get arrested,’” said Tom, a camp resident. “And just backed a dump truck, literally backed a trash truck up to our tent and started loading stuff in.”

Tom shares a large tent with his friend and business partner, Mark. They run a sidewalk vending business selling bracelets and art. Though much of their wares were recently gobbled by a trash truck, along with Tom’s birth certificate and Social Security card. He had just collected the two together in order to obtain a picture ID. Now he said he’ll have to work backward from the ID to get his Social Security card and birth certificate again.

Mark thought the students could have done more.

“Half of GW should have been down here. There should have been so many students down here that the cops would have had a problem,” Mark said. “[But] they can’t even get their own friends to come down here and support us.”

Mark thinks everyone should do more: neighbors, lawyers, faith leaders, homeless service and advocacy organizations and campers elsewhere in the city. “Your people have to stand up with us too. You can’t just report. You gotta be active,” Mark challenged the presence of Street Sense Media. “I get it, but when it’s that bad, you’ve gotta take a stand.”

The camp had become visibly established in recent weeks. There was a large blue canopy and a full-size gas grill. “You should have seen our setup a week ago,” Tom said. Mark described a woman from the area that stopped by and asked what the people in the camp needed. He told her it would be nice if they had something to cook with, imagining a small propane camp stove.

“It wasn’t the most usable grill, it had no wheels,” Mark said. “But we got it level and cooked on it. We really liked it.” Now the pair keeps everything packed up, in case they have to move again.

Encampment cleanups are an interagency effort — outreach from the Departments of Human Services and Behavioral Health, disposal via Public Works and security from MPD — all coordinated by the Office of the Deputy Mayor of Health and Human Services. Cleanups do not happen at random and they are not necessarily frequent. Eight cleanups were conducted in the month of October.

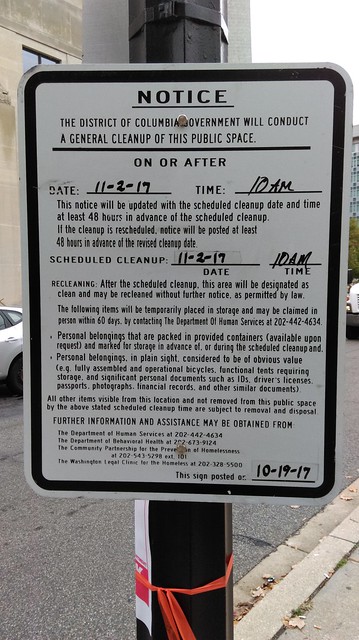

The deputy mayor’s office maintains a calendar of sites that may need to be cleaned. Tuesdays and Thursdays are designated to carry out the task, when necessary. The whole operation is outlined in a document that was updated in November of last year, including how much notice camp residents should have before a cleanup, what property may be disposed of, what property may be stored and much more. (The previous version was signed in 2012).

The city must post signs 14 days before a cleanup will take place. And if a site is added to the cleanup calendar, it has probably already been visited by outreach workers, according to Sean Barry, communication director for the Office of the Deputy Mayor of Health and Human Services. “But certainly, if the location is added to that calendar, it will accelerate the outreach of people making those visits to warn people about the cleanup and have that conversation about what services are available and try to connect that individual to services.”

The city does not want to ambush people or take their belongings. It does want them to be prepared to move along, in accordance with the law.

Mark, Tom and the rest of the tent community were still caught off guard on Nov. 2. They had seen similar signs posted in August and September, but the city never followed through on them. “So last Thursday we didn’t know what was going to happen until they showed up with trucks and started throwing people’s stuff away,” Mark said.

At a recent D.C. Interagency Council on Homelessness committee meeting focused on emergency response, the need to clarify communication to residents surrounding encampment cleanups was on the agenda.

Storage space is not infinite, Barry said, but the city provides up to two large tubs for storage by each camp resident that can then be kept at the Adam’s Place Daytime Service Center in Northeast for up to 60 days. It is also the practice of the Office of the Deputy Mayor of Health and Human Services to preserve all personal documentation and ensure that it is not disposed. The office had not been made aware of Tom’s discarded birth certificate and social security card, according to Barry.

The updated city protocol, storage plans and other facets of the cleanup projects are relatively streamlined when compared to the 3-week series of cleanups contesting ground in Foggy Bottom during November 2015 near the Watergate complex, marking the Bowser administration’s commitment to encampment cleanups.

Living in any “temporary abode” on public property in the District has been illegal since 1981, though enforcement has varied. Confusion ran high during the 2015 cleanups, both among camp residents and seemingly among city personnel assigned to the scene. Now, at each cleanup, there is always a spokesperson for the deputy mayor’s office, a coordinator for the city workers and a uniform set of answers for the homeless community.

[Read more:Tent city dwellers highlight poor shelter alternatives]

Many campers seem to have streamlined their own operation too. Earlier this year, online news outlets DCist and ThinkProgress both characterized the city as playing “whack-a-mole” with people living in tents — noticing that an area would be cleared on a Tuesday or Thursday morning and the tents would often return the same night.

More “humane” sweeps still bad if there’s no housing. D.C. plays Whack-a-Mole with homeless encampments” by @PykeA https://t.co/QdW3AMWQPT

— Maria Foscarinis (@Mariafoscarinis) June 29, 2017

That is exactly what happened on Tuesday, Nov. 2 on E Street. A caveat in the notices posted for encampment cleanups provides that once an area is cleared, it may be cleaned again at any time. In practice, that meant the same interagency effort would reconvene on E Street the morning of Tuesday, Nov. 7.

When Tuesday came, a similar scene unfolded. Some of the GW students returned and helped people dismantle their tents. They even rented a small U-Haul van to try and help people transport what they couldn’t store, move, or bear to throw away. Some campers took advantage of the city’s storage offer. Still no one elected to pursue connection with city shelters, according to Barry of the deputy mayor’s office. Many items were moved around the corner or across the street to be brought back that night.

The items in gray bins will be stored by the city. The items organized and moved to the sidewalk beyond the cleanup area were left alone. Photos by Eric Falquero

The items in gray bins will be stored by the city. The items organized and moved to the sidewalk beyond the cleanup area were left alone. Photos by Eric Falquero

The difference that morning was that it began to drizzle. City workers wore jackets and sweatshirts. The cleanup was eventually cut short as the rain picked up.

A couple, John and Maisha, residing in a tent down the hill from the others and saddled between the Eastbound and Westbound ramps of the E Street Expressway, were told they would not be forced to decamp in the rain. Theirs was the only tent still standing.

As he peered out through the tent’s screened flap, John invited the cleanup coordinator to “come in and get ya some heat.” She declined and he asked for a meeting with the mayor — not the deputy mayor — about the city’s cleanup efforts.

“Um, realistically?” the coordinator asked.

“Realistically,” said John, “It doesn’t have to be in the public or in the paper. I just want her to feel my heart.”

The coordinator said that another repeat cleanup effort would be held Thursday morning, Nov. 9 to make sure the area was clear.

Meanwhile, the city vehicles left and everyone who had taken their tents down was caught in an icy downpour that lasted for approximately one hour.

When outreach workers visited the site the morning of the anticipated Nov. 9 cleanup, campers who had remained requested sweatpants, socks and gloves because their clothes were still soaked from two days prior. Near record lows were predicted for the weekend.

“We had to move all this stuff over there. Then we moved it back,” said Simon, another camper across from the State Department, “Now it’s going to be winter time, and there’s no place to sleep. Then you gotta start sleeping on the freaking— anywhere you can possibly find.”

Simon shares his tent with another man whose tent was washed away in recent storms.

It appeared that the city still planned to return on the morning of Nov. 9. Two MPD units parked in front of the State Department and a public works truck pulled up at the end of the block. However, when the first trash truck arrived, it continued beyond the camp. Several blocks farther down E Street, three different homeless men and women were having their temporary abodes cleaned up that day.

Fortune continued to favor the folks between 20th and 21st Streets when a faith group based out of Maryland offered to put several, if not all, of the campers up in hotels to weather the cold for three days.

The optics of a homeless encampment cleanup are jarring. “I am very much aware that the Bowser administration is aggressive about removing homeless people and their tents,” said a District resident who works nearby and witnessed part of the Nov. 2 cleanup. “I do not know how aggressive they are about finding some housing for those individuals.”

Beneath the surface, the city continues to grapple, like many others, with intertwined housing and homelessness crises. D.C. Council just advanced a bill more than a year in the making that codifies in over 30 pages the rights of homeless people, and the rights of the programs and people that serve them.

[Read more: Controversial HSRA bill passes first vote]

One of the most volatile debates between critics and supporters of the Homeless Services Reform Act Amendment of 2017 is whether the city will soon be asking for too much proof of D.C. residency or proof of homelessness to qualify for assistance. The fear that drives this conversation is whether homeless people from outside of the District come here for better services. But those requirements only affect family shelter placements, not single individuals in tents.

In a broader sense, the bill aims to acknowledge that homeless services must be more housing-oriented than they have been historically, but that the city’s emergency services for responding to homelessness cannot solve the housing crisis.

A number of the people at the E Street camp are not from the District. Mark, a veteran, prefers to say that he’s “from America” because he has lived in so many places, most recently Kingston, NY. The couple whose tent was saved by the rain, John and Maisha, came here from Kentucky looking for a fresh start. But they didn’t come here for city services, they came to see Maisha’s uncle, who lives in the area. But they have been struggling since parting ways.

A silver lining for the couple is the camp’s proximity to both Miriam’s Kitchen and GWU Hospital for meals, health care and case management. Maisha struggles with serious asthma, arthritis that can make her whole body lock up, and sickle cell anemia. John has hemophilia and was recently diagnosed with cancer.

The infrastructure and amenities of Foggy Bottom are a draw for Mark as well. He was previously offered housing by the District but declined because the room he was shown was too far from Metro bus or rail access in Southeast and he did not believe it would be possible to reliably commute to a job.

[Read more: There are no centrally-located city-run shelters for individuals]

Ultimately, on Nov. 9, the E Street campers between 20th and 21st Streets were told that there would be no more cleanup efforts until new 14-day notices were posted.

“When do you say ‘no’ to bad laws?” Mark said, still hoping to see students or injunction-bearing lawyers en masse the next time his camp is set to be shut down. “I’m having nightmares now that they’re going to back up a truck and they’re just going to pick up our tent with everything in it, us included.”

Simon, frustrated by a year of fruitless efforts chasing employment and the bleak outlook that comes with it, said that he did not want to hear about shelter. “I’m a low-class job situation. Not middle class, not high class. Low class. I mean, homeless people here are the low of the low class,” Simon said. “You expect every homeless person to get a job?”

He suggested that the one thing the city could do is to focus on building more housing. He and Mark, in independent interviews, suggested building more single room occupancies, as opposed to full apartments, to house low-income individuals.

The Bowser administration has made unprecedented investments in housing. Since January 2015, $276 million has been added to the Housing Production Trust Fund, which has supported the production or preservation of more than 3,300 affordable units that can house more than 7,200 residents, according to a release from the D.C. Department of Housing and Community Development.

Cities across the nation are grappling with how to handle homeless encampments. Local governments walk a tense line between adequately serving vulnerable unhoused citizens, addressing public health and safety concerns for all, managing blockage of public space and responding to complaints from business owners and housed citizens. Most eventually raze their “tent cities,” such as Greensboro, NC, Santa Ana, CA, Dallas, TX, Chicago, IL and the nation’s capital.

John, from the E Street Camp, suggested that The George Washington University set aside space on the private campus land, where safety and sanitation would be maintained, to allow people to camp there. He and Miasha said they could afford and would gladly pay a fee up to $25 per week to camp somewhere sanctioned until they find housing. Somewhere that would allow them to continue accessing the hospital and other service providers.

Several cities on the West Coast have been pioneering this strategy. Seattle, WA opened its first city-sanctioned camp in 2015 and now operates six sites and is looking to expand. San Diego, CA opened their first city camp last month. Oakland, CA sanctioned a camp in 2016 that tragically went up in flames in May. Now Oakland has three camps planned that will shelter people in Tuff brand sheds as opposed to personal tents. On the private side, a church in Amarillo, TX obtained land earlier this month for the express purpose of providing space for homeless campers.

Seattle, like D.C., has a complex multi-year plan to drastically reduce homelessness. The city’s sanctioned encampment areas are billed as a band-aid to carry some people through until systems are in place that can adequately meet their needs. Unsanctioned encampments continue to be shut down. “These changes will not be fully implemented until 2018,” according to Seattle.gov. “In the interim, the City needs more shelter beds and better low-barrier options, such as sites that allow partners, pets, and possessions … Authorized encampments offer a safer alternative that can help stabilize the person before transitioning indoors.”

D.C.’s own strategic plan aims to make homelessness “rare, brief and nonrecurring” by 2020.

“The encampment response is not the District’s strategy for homelessness,” Barry of the Office of the Deputy Mayor of Health and Human Services said on-site at the Nov. 7 cleanup on E Street. “It is one piece of what we’re doing and it really is driven by both the fact that camping is illegal but more importantly that encampments as a housing solution are not a workable solution for the health and safety for either the inhabitants of those encampments or others who use that public space.”

The scale of the problem is daunting. There are 7,400 people experiencing homelessness and more than 40,000 names on the closed waiting list for assistance from the D.C. Housing Authority.

[Read more: D.C. Housing Authority to freeze waitlist]

“Where else are we supposed to go?” Simon asked in the meantime. “We don’t have a home. Are you going to put every homeless person in D.C. in a shelter? Good luck with that. All of ‘em are not gonna fit.”

Emma Rizk and Ben Burgess contributed reporting.

Update

An abridged version of this article ran in print on Nov. 15. At that time, a D.C. Council Committee on Health oversight hearing was expected to discuss this topic. A recording of the hearing is now available in the D.C. Council archive. The hearing starts at 12:36: http://dc.granicus.com/MediaPlayer.php?view_id=2&clip_id=4223.

Correction

The print edition also incorrectly stated that the District’s temporary abode ordinance has been in effect since 1990. It has been updated here to reflect the correct year, 1981.