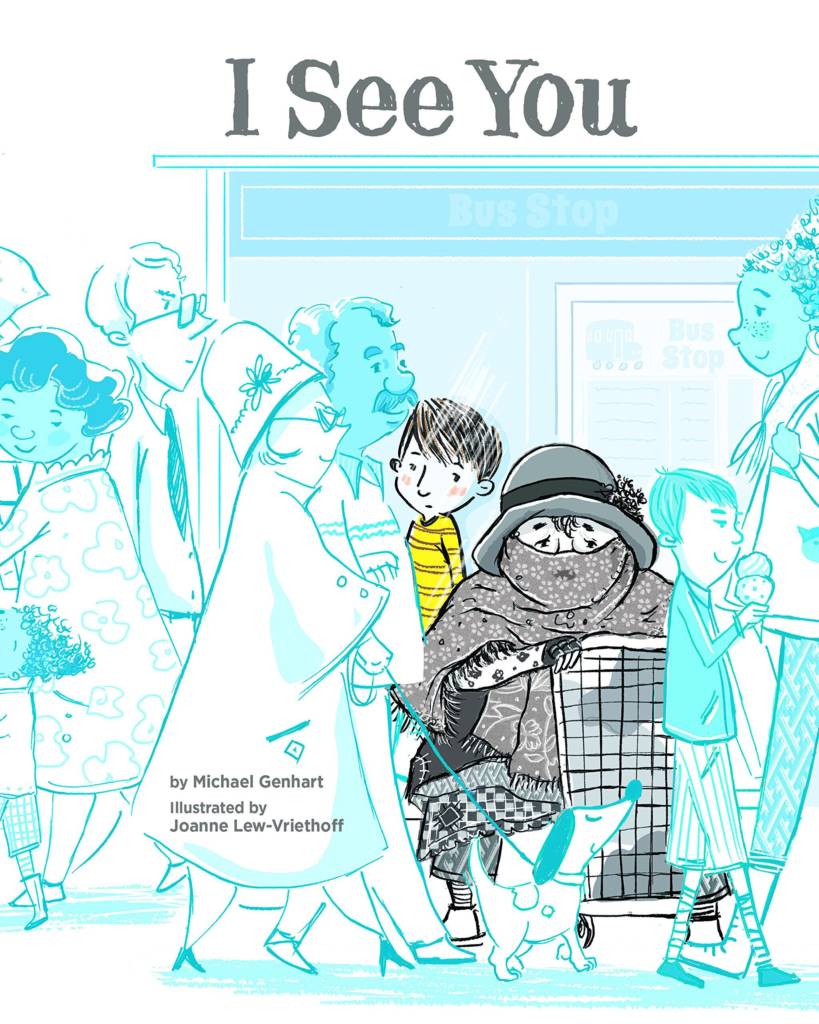

In his new children’s book, “I See You,” Michael Genhart tells the story of a woman experiencing homelessness and a young boy who is the only one who seems to notice her. The catch is that he tells the whole tale without writing a single word.

The story, told entirely through illustrations by artist Joanne Lew-Vriethoff, shows a little boy’s growing curiosity and concern for a local homeless woman he sees from his window every day. He watches the daily stigma and hardship she experiences over the course of a year as she sits at the bus stop.

Throughout most of the book, the woman is illustrated in black and white while the other smiling people who sit at cafes, walk by with their shopping bags, paste advertisements for “Luxury Condos on Sale,” or wait for the bus are depicted in vibrant color. When people do take notice of the woman, it is to pinch their noses or to sweep her angrily off their doorstep. Her humanity remains invisible. In the end, when the boy gives the woman his favorite blanket as a holiday gift, the bystanders finally take notice of her. The boy’s gift returns her color and her visibility to the rest of the world.

Genhart said he chose not to use narrative in the story because he “didn’t want to tell people what to think or feel.” Illustrations facilitate more questions and can spark a conversation in the classroom or between parents and children. The use of color shows the contrast between everyday life for many people and the isolation and invisibility felt by the woman experiencing homelessness.

The author is a licensed clinical psychologist who has written several children’s books about topics that can be difficult or uncomfortable for parents to broach, such as jealousy and LGBTQ pride. He chose to write about homelessness, he said, because it is a worldwide problem that he wanted to address the best way he knew how.

The compassion of children is a main focal point of the book. “I think it is human nature to care,” said Genhart. “But homelessness makes us uncomfortable, overwhelmed. Whatever gestures we might want to make seem like they’re not enough, so why bother?”

However, like the little boy in the story, children tend to have questions and compassion about issues many adults have ceased to notice. His book shows that children notice and learn from everything, including the way some adults act fearful of or indifferent towards the homeless. “I think kids are not afraid,” said Genhart. “As adults, we shouldn’t teach them fear.”

Instead of fear, Genhart’s book seeks to teach kids curiosity and empathy. In the back of the book is information and advice for adults about how to broach the subject of homelessness with their children, and how to answer their many questions in a way that fosters compassion and understanding for the people experiencing it.

There is also information about how to help people who are homeless, such as by preparing small care packages with snacks and hygiene products that can be kept in pockets. According to Genhart the book has already been used in classrooms as well as by parents, and he has received “super positive reactions.” According to one parent, the book cover caught the eye of her three-year-old son and led to a discussion about some of the hardships faced by people experiencing homelessness. A fifth-grade student wrote in a letter that she liked the book “because it gives a message to the world that everyone’s the same even if you are poor, rich, Spanish, American, Muslim, black, white or homeless.” Many other readers were inspired to recreate the care packages from the book’s instructions, or to design their own projects.

By including information for both children and adults, Genhart said he “really wanted to start a conversation in a natural way.” He suggested that parents follow their child’s lead when deciding when or how to begin talking about homelessness, and to give age-appropriate, honest answers like the ones in the back of his book. Parents should “address both the content and feeling of the question,” said Genhart. The narrative and morality of the story may be sufficient for younger readers, but older children might benefit from discussing homelessness in their own city using resources from the back of the book.

Genhart noted that adults are likely to learn as much from his book as their children. Children’s questions can lead to reflection and further research, and their desire to help can rub off on parents and teachers. Ultimately, adults can relearn to acknowledge and feel compassion for the homeless, even if this just means saying “hi.” “I will consider this book a success if it was able to build a conversation,” said Genhart.