A law meant to protect consumers by prohibiting businesses from refusing to accept cash took effect on April 4. There’s just one problem — it’s unenforceable. Or, rather, D.C. officials put off enforcement during the public health emergency, and they haven’t allocated the $750,000 over four years that the city’s chief financial officer says is needed to pay for its enforcement.

“Banning the use of cash is a discriminatory practice,” then-Councilmember David Grosso said in 2019 when he introduced the measure. Such a policy “disproportionately impacts the 10% of D.C. residents who are unbanked, and an additional 25% of residents who are underbanked and may not have access to a credit card.”

The council approved the bill unanimously in December 2019.

Mayor Muriel Bowser did not include funding to enforce this protection in her budget proposal for fiscal year 2022, and the D.C. Council did not bring up the issue at last week’s budget work session. Without enforcement of the law, businesses in the District are dropping cash payment options more rapidly than anywhere else in the country, according to one recent study.

The share of Square clients in D.C. that are completely cashless expanded from 15% in 2019 to nearly 40% this year, according to the company’s data, which analyzed transactions processed by its software and card-reading equipment. Square’s analysis excluded businesses that had prolonged closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. So, of the D.C. businesses using Square that stayed active during the health crisis, two-fifths didn’t accept cash.

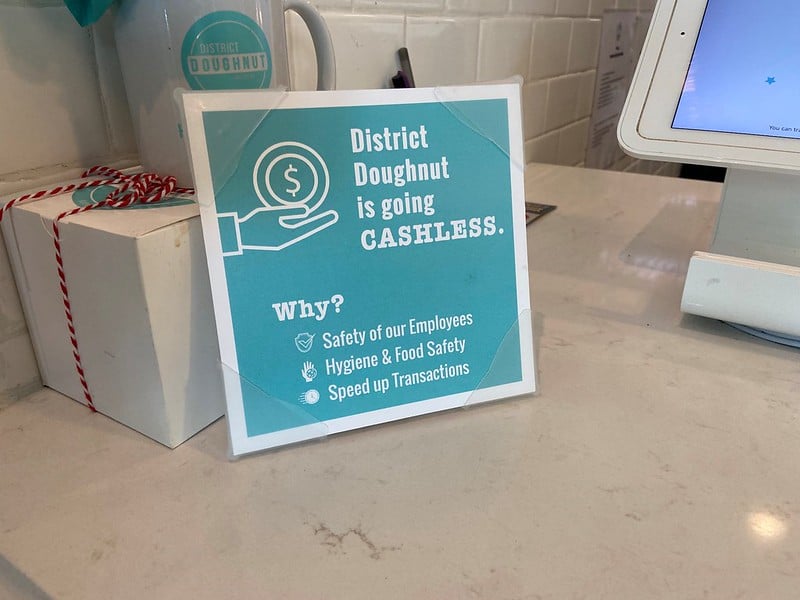

Several D.C. legislators introduced the Cashless Retailers Prohibition Amendment Act in early 2019 — well before the pandemic — in response to a growing number of restaurants, stores, and shops eliminating cash from their business models, opting instead to accept only credit cards or other electronic forms of payment.

“This has been a nationwide trend, backed in some instances by credit card companies like Visa, which have provided short-term funding to businesses that agree to stop accepting cash from their customers,” Grosso said.

Poor Americans and people of color are more likely to depend on cash

The cashless trend is influenced in part by a shift in consumer habits. Roughly one-third of Americans say they don’t normally use cash for purchases they make during the week, according to a 2018 survey by the Pew Research Center. But even as consumers and businesses across the country became more comfortable without cash, many people faced difficulties because they lacked access to cashless forms of payment. People who are most affected by businesses going cashless are generally lower-income, elderly, and people of color.

Citing data published by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp., advocates testifying at a February 2020 council hearing on the new legislation noted that roughly 8% of residents in D.C. do not have a bank account. Also, 21% of District residents are underbanked — which means that, while they have bank accounts, they do not have ready access to a card for financial transactions. The same data also found that Black and Hispanic households across the country were far more likely to be unbanked than white and Asian households.

Speaking before a D.C. Council vote on the cashless prohibition rule last December, Grosso said that cashless businesses are inherently discriminatory toward specific populations. “By denying patrons the ability to use cash as a form of payment, businesses are effectively telling lower-income, undocumented [and] young patrons that they are not welcome in their establishments,” Grosso said.

Grosso’s statement echoed the concerns of other advocates who testified earlier in the year in support of the new law.

Cash may protect consumer privacy but present a hazard to businesses

In an interview with Street Sense Media and The DC Line, Meryl Chertoff, director of the Georgetown Project on State and Local Government Policy and Law, gave a number of reasons that most retail businesses should be prohibited from being completely cashless. These reasons, she stated, go beyond racial disparities: Protecting a consumer’s right to use cash as an option is also a matter of privacy. “Every time you use a card, you leave a fact about yourself, you leave a piece of data. Every time you buy a pack of cigarettes, there’s a record you bought those cigarettes,” Chertoff said.

Even as councilmembers showed broad support for the ban on cashless retail, some expressed concerns about how the legislation might impact local businesses. Then-Ward 4 Councilmember Brandon Todd was careful to note that he did not think cashless businesses were intentionally trying to discriminate.

“Some small-business owners value the additional safety that comes with not having cash on hand,” Todd said, alluding to robbery and employee theft.

Todd, who ultimately voted in favor of the bill, successfully offered an amendment to clarify the ability of cashless businesses to install devices that would allow patrons to load cash onto prepaid cards they could use for purchases there. Under the law, customers who load cash onto these cards cannot be required to pay any extra fees.

DC businesses adapted to cashless during COVID. Will cash come back?

By the time the pay-with-cash protection became a reality, the world had changed. D.C. Council meetings were no longer in-person and people no longer freely visited businesses. Drawing on guidance from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, shoppers and stores more frequently opted for touchless and cashless payments to avoid direct physical interactions.

The pandemic also changed the way the council viewed the issue. Given public health guidance, legislators wrote a public health exemption into the law, leaving implementation and enforcement of the ban for a time when things return to normal. The law is not in effect during a public health emergency declared by the mayor.

Even without any certainty or timetable on enforcement, some businesses are making adjustments as they plan for post-pandemic operations. A Georgetown University campus co-op will include a pay-with-cash option for staff and students this fall, according to a report by The Georgetown Voice. The store, which had been cashless since February 2018, decided to make the forthcoming change in response to the law, operators told the Voice.

None of the councilmembers contacted for this article offered to provide comments about the status of funding for this legislation. A spokesperson for the Department of Consumer and Regulatory Affairs confirmed there is currently no plan to fund enforcement of this law.

This article was co-published with The DC Line.

Will Schick covers DC government and public affairs through a partnership between Street Sense Media and The DC Line. Year one of this joint position was made possible by the Poynter-Koch Media and Journalism Fellowship, The Nash Foundation, and individual contributors.