Parcel 42 in Shaw turns into a live-in after alleged failed promises by city government

Parcel 42 was once an unassuming plot of land, devoid of any buildings on the corner of R and 7th NW in Shaw. It suddenly became a battleground and a symbol on July 10, when protesters began a live-in to fight for their right to affordable housing. Now, Parcel 42 is a microcosm of Washington’s greater ongoing struggle to provide shelter for all.

Organizing Neighborhood Equity DC held a block party that afternoon, prior to the occupation. The celebration had a serious angle: neighbors enjoyed not only refreshments and music, but speakers on equal land development and books to borrow about successfully arranging protests. Someone chalked a hopscotch with seven squares of “Fight” and “Fight some more”, then two squares saying “WIN”, culminating in “Housing for All People”.

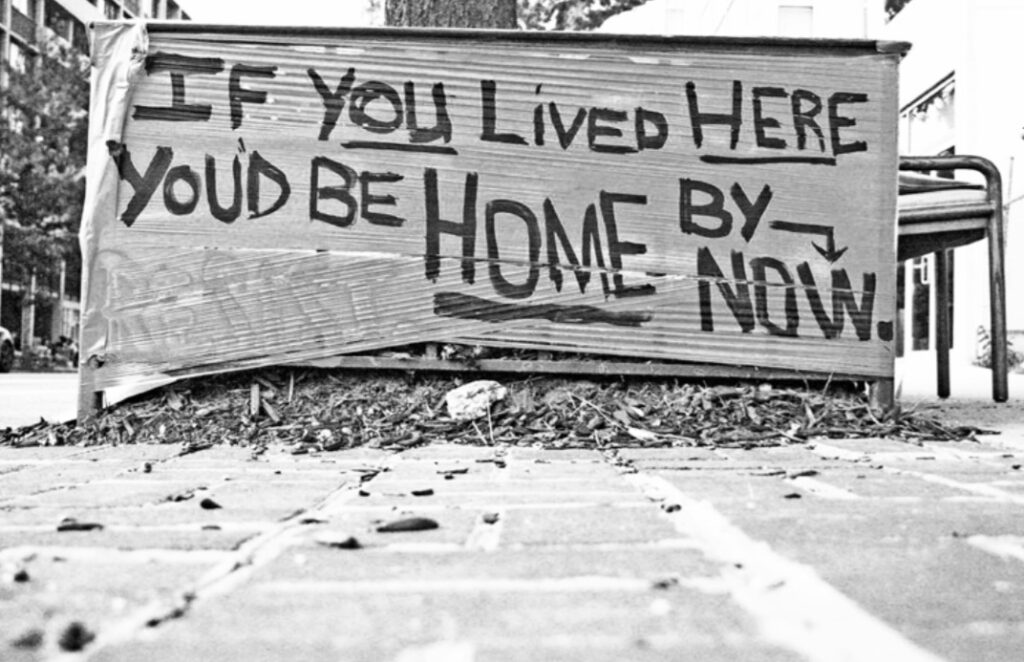

For the grand finale, attendees marched down the block to Parcel 42 at 5 p.m and began pitching tents and erecting signs under the watch of neon-green capped legal observers and two police officers. “Fenty Broke his Promise,” said little plaques and big banners on the fence enclosing 42.

The occupation is the crest in ONE DC’s struggle in that classic vein: pressuring a government to make good on its pledges. They once believed that this space had a future to be developed like its sibling, Parcel 33, into a mixed-income apartment building. Yet they found what they considered a settled agreement soon vanished.

The effort stretches back to 2002 when the group began working with Shaw residents to form a strategy to develop new housing. The team surveyed other neighborhood residents and explored vacant area lots’ ownership. Once they identified their targets in 2003 they began to meet with possible partners, such as similar activist groups and developers committed to affordable housing. The next four years saw land surveys, negotiations with a potential development team, appraisals and cost estimates.

By June 2007, even with specific plans to present, ONE DC and its Shaw partners could not secure a meeting with the D.C. government to seek their commitment. After many weeks of asking, the specter of a sit-in was raised instead, which prompted officials to meet with ONE DC members at once about an assurance to make Parcel 42 affordable. The next month, Deputy Mayor Neil Albert agreed to a $7.8 million government subsidy for the development.

In September, a coalition called Parcel 42 Partners was formed of the only bidders that met two requirements: a readiness to create rental properties for households making less than $50,000 a year and receptivity to community input. Members brought petitions door-to-door in support of the partners and collected over 500 signatures. Many residents called and e-mailed the Deputy Mayor to express their support. The campaign led to Mayor Fenty announcing Parcel 42 Partners as official developer of Parcel 42 on November 14, 2007.

With the Partners’ position cemented, ONE DC members met them in December to draft a Community Benefits Agreement and review the first draft of a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) the Partners had submitted. It was drafted on terms similar to the MOU for Parcel 33, a parallel development in the neighborhood. In it, they summarized their dedication to providing affordable rent appropriate for renters and ways the development would integrate with the Shaw neighborhood, from Shaw-targeted jobs to 10 percent community ownership and even perhaps a community center.

At this point, the collaboration began to yield disappointment. The MOU was successfully signed for Parcel 33, but had accepted less-than-desirable terms for it, with the expectation that better conditions would be met in Parcel 42’s agreement.

The city came to them in negotiations, said Rosemary Ndubuizu, a community organizer for ONE DC.

“It was sort of a, ‘You take this on 33, we’ll do that on 42,’” she said. For the former, the city agreed on tiered affordability rates for just 45 of 180 units, which was far below ONE DC’s target. Nevertheless, they cooperated, thinking they’d reach a better agreement for 42, up to ninety-four units on another tiered scale.

In April 2008, Parcel 42 Partners reported that they had been presented a government subsidy of just $4.98 million. Rents could only start at 60 percent of AMI, instead of 30 percent, and there would be no other community benefits. According to ONE DC, certain officials strongly suggested the Partners end communication with them, which was advice the developers took. The Parcel 42 Project would not return requests for comment. (When contacted by Street Sense, a representative for Mayor Fenty, Mafara Hobson, affirmed the government’s continued commitment, saying, “The Administration is and will continue to stand by its agreement to include affordable housing in this project.”)

In May 2008, members met with Neil Albert, who restated his devotion to greater affordability, yet the submitted rents and subsidy did not change. In September, they received word that Albert would not attend a previously-proposed roundtable of groups involved with the 42 project.

Though the necessary elements for success on 33 were transpiring, all promises about 42 evaporated.

“We now know, don’t trust this administration,” Ndubuizu said, noting the possible presumption of understanding where there truly was none.

Previous instances of direct action failed, including a protest at Fenty’s home doorstep in 2008. A construction start date for 42 was nonexistent, the city’s apparent promises shunted. ONE DC resolved to air their ill-use by the administration and inveigh against Washington’s acute shortage of affordable housing in one gesture.

The live-in was born.

Protesters set up their encampment swiftly and efficiently on that crucial afternoon. A list of rules, including prohibitions on drinking and stealing, was drawn up. Leaders created a schedule of meetings twice daily at 8 a.m. and 8 p.m. Sentinels at the gate handed out flyers explaining the protest’s motives and goals.

As the work week began, so did outside attempts at removal. Monday brought a police captain from the third district and then beat cops. On Tuesday, the property manager whom the city had assigned to 42 arrived. He tried to cajole them into leaving, but ceased after 45 minutes, estimated protester Ron Harris.

Property maintenance workers came Wednesday to eject the protesters, who would not budge, replying that such an act was not in either the crew’s or owner’s authority. ONE DC marked its last day of leading the protest, Thursday, with a party marking the handover of 42 from exclusively ONE DC leadership to a committee of local leaders. As an affiliate of the Take Back the Land Movement, ONE DC wanted the occupation to be in keeping with its principles of empowering impacted communities and giving neighborhoods their own local control.

For all the frustrations leading to this event, participants feel it was a constructive and positive episode.

“It’s been very empowering for a lot of people,” said one supporter. “We just hope something can come out of this.”

A great number of protesters share the disillusionment Ndubuizu voiced.

“Fenty has a lot of tricks up his sleeve,” said Kim, a Shaw resident of over 30 years who did not give her last name. She found inconsistency in his actions, citing that though he has forced the closure of many go-go clubs, a part of the culture of neighborhoods like Shaw, he allowed the funeral of go-go legend Benny A. Harley, aka Little Benny, to be held at the convention center. “He’s not about the community. He’s not about the people.”

Perhaps if Fenty made good on his word, she suggested, the deaths of two boys in a shooting days ago on the Kennedy playground could have been prevented.

“Build something for kids to do,” she said. “How can you expect them to aspire to be something when there’s nothing?”

ONE DC member Virginia Lee found it regrettable that they could not form a coalition of other organizations, who could not join the endeavor, being too occupied with different issues in their own purviews. “We wanted to bring into our own community the teachers, the firemen, who could make it a more diverse community, in addition to longtime Shaw members.”

The failed aspirations of 42 resulted in one concrete move by the government: introduction of legislation by Councilman Michael Brown to change the current method for determining AMI. A representative of his predicted the bill would be heard in September after the summer recess, but said he felt the councilman’s office was not in a position to comment on the government’s actions.

AMI is currently determined not from salaries earned by residents of the District alone, but by what residents of the greater metro area earn, such as incomes from wealthy suburbs in Maryland and Virginia. This method yields a figure of $103,500 a year for a family of four when the surrounding suburbs are taken into consideration. If AMI were computed from incomes of only District residents, as the Brown bill proposes, the result would be lower.

As ONE DC notes, fewer than 20 percent of D.C.’s housing units are affordable for those making under 50 percent of the D.C. Metro AMI. Such a disparity is especially glaring, said Harris, when one considers the December 2008 city council proclamation that D.C. is a human rights city.

Though the live-in is currently flourishing, with classes and workshops scheduled for this week, the future of 42 is unclear.

“I don’t know what their intentions are, only what the reality is,” Lee said.