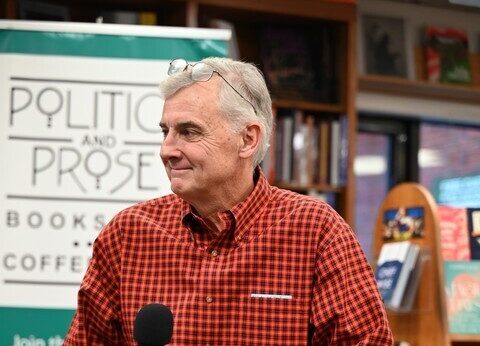

For more than 50 years, renowned educator, activist and author Jonathan Kozol has dedicated his career to working with and chronicling the lives of some of America’s poorest children and their families, particularly in the South Bronx. Through more than a dozen books Kozol has taken readers on a journey allowing them to see what life is like for those living in poverty.

His latest, “Fire in the Ashes: Twenty-Five Years Among the Poorest Children in America,” was the topic of discussion at the Sidwell Friends School on Sept. 4th.

Fire in the Ashes shares the heartfelt tales of children in the South Bronx who must face the many hardships and obstacles that plague the communities they grew up in. Many of these children and families lived in some of the South Bronx’s notorious homeless shelters. Over the years Kozol has developed deep and lasting friendships with these children and their families.

Some of the youth that he encountered have overcome these challenges and made it out, while others became victims of the inner city. In the book, Kozol reveals and highlights the inequalities of education in urban schools. Everything that he writes about comes from firsthand observations.

First, as Kozol writes, the low-performing public schools that these children attended fail to provide adequate learning opportunities and hinder their academic growth. Secondly, their families are broken up by drug addiction and crime, which results in emotional problems and limits their social mobility.

Lastly, violence, crime and drugs plague the community in which they were raised, and their neighborhoods do not provide resources and opportunities. As a result, many of these children become marginalized and disenfranchised, making it very difficult to progress and escape these difficulties.

Kozol grew up in privilege in Cambridge, Mass. During the height of the Civil Rights Movement in 1964, Kozol moved from Harvard Square into a poor black neighborhood of Boston and became a fourth grade teacher. He has been working with children ever since and has devoted his life to providing equal educational opportunities to children regardless of race or economic status.

In the late ‘80s and throughout the ‘90s Kozol spent his time many children living in New York in a section called Mott Haven, which was then and is still today the single poorest neighborhood in all of the South Bronx, and remains the poorest congressional district out of all 435 congressional districts in America.

“I thought I had seen poverty in Boston but I’d never seen anything on this scale before,” said Kozol.

Kozol noted that many of his readers frequently ask him what happened to those children? Did he keep in touch with them? How many of them survived? How many did not? And for those who did survive how did they obtain a decent education? How far did their education take them? What are they doing now?

Kozol said that some of the children he encountered never did recover from the battery they underwent in schools that were among the worst he had ever seen.

“Streets where needles and crack cocaine were almost anywhere. Three of the boys who suffered most, I’m sad to say, are no longer alive,” Kozol said.

Still, Kozol recounts the stories of children who found the strength to defeat their dire circumstances.

“There are many children in the book who battled back courageously against the formidable obstacles they faced. And with the help of grown-ups who intervened at crucial times and loved them deeply and fought aggressively on their behalf have won triumphant victories. Those children are the fire in the ashes whom I celebrate today,” said Kozol.

A number of teachers were in attendance. Kozol has a high adoration for teachers and praises them for the role that they play in children’s lives. Kozol addressed the issues of public education. Among the topics discussed, class size, standardized testing and the No Child Left Behind Act were the most prevalent during the talk.

Some of the children that Kozol mentions in his book prevailed in part because of charitable people. Scholarships and philanthropy are a great aid to students who come from poverty stricken neighborhoods.

“Charity is a lovely thing I never turn it down I assure you. But charity will never be, it never was, it isn’t now a substitute for systematic justice,” Kozol said.

Low-income students such as the ones in this book should not have to look for charity to receive a decent education in the wealthiest nation in the world, according to Kozol.

“Only equal, universal, non-seductive public education can ever close the gap between the classes and the races in America,” Kozol said.

Anna Ernst, a social worker from Bethesda was in attendance. She read Kozol’s Savage Inequalities: Children In America’s Schools while attending Oberlin College in Ohio. The book discusses the disparities in education between schools of different classes and races. After reading the book, Ernst was deeply moved by Kozol and wanted to explore these issues more in depth.

“He painted a picture of public education that I had never seen before,” Ernst said.