Early in his career, Joseph Young couldn’t fathom why someone would want to photograph old, worn-down buildings.

“I used to ask myself, ‘Why would they want to do that?’” Young said. “I just thought it was so ridiculous.”

But after he joined the community where he still resides, those buildings soon became more to Young than just withering structures lining the streets. They were the homes of his neighbors being neglected and the locally-owned businesses being demolished. He watched gentrification set in for 15 years.

Then Young began doing what he thought he’d never have a reason to: he took pictures of the dilapidated buildings.

He started with the H Street Northeast Corridor, documenting the area as gentrification intensified. There was a Black woman who used to own one of the restaurants and a Black beauty school where people could learn cosmetology, among other buildings.

Soon enough, the area transformed. Businesses closed and construction of apartment buildings got underway. Young continued to take pictures. Then, he learned about the demolition of the historic Barry Farm neighborhood in Southeast D.C., which began with land given to thousands of freed slaves after the Civil War. His interest was piqued once again. An initiative to convert the public housing community that has since been built there has languished without adequate funding for more than a decade. More recently, the plan itself was held up when the D.C. Court of Appeals sent it back to the zoning commission. In the meantime, temporary relocation of residents to make way for construction and demolition was allowed to continue. Everyone has moved.

[Read more: Board votes to approve portion of Barry Farm Dwellings as a historic landmark]

Young photographed the dilapidated homes and collected objects left behind by residents who had deserted their apartments. He gathered empty bottles, shoes, clothespins and other odd items that told the stories of low-income families that had no options.

All of that work has led him to where he is now: approximately 160 of his photos were accepted into the collections of the Smithsonian Institution’s Anacostia Community Museum on Feb. 6. They show the transformation of D.C. neighborhoods and symbolize gentrification occurring across the globe.

“His photographs, even the ones without people in them, have a very human element to them,” said Samir Meghelli, senior curator with the Smithsonian. “They really capture the essence of a place, of a moment in time. This isn’t just someone that’s photographing for photographing’s sake. He’s really deeply tied to and connected to the city and has legitimate concerns.”

Young, born in Memphis, Tennessee, in 1956, got started with photography in the early ‘70s when he would take pictures on disposable cameras and have the local drug store send them out to be developed. After taking an introductory photography class in college, Young purchased his first “real” camera, a Canon AE-1.

He practiced photographing family members while traveling and slowly honed his craft. Still, it wasn’t a serious hobby for Young, who came to D.C. from Los Angeles in the ‘80s.

He took on a job at a bookstore before working as a full-time reporter with the Washington Informer in 2006. While out on his assignments, he said he would often be asked to take pictures to accompany his stories.

Denise Rolark Barnes, the publisher of The Washington Informer, said Young was “thoughtful” in his reporting, which eventually gave way to a full-blown passion for photography.

“It seemed as though once he focused on the lives of the people that he was writing about, he realized he could tell a story through photos and I think became really passionate about documenting folks’ stories through photos,” Rolark Barnes said.

Photography soon became more than just a hobby, and Young’s focus turned to documenting the rapid transformation and erasure of the area around him. For that reason, the pictures he submitted to the Smithsonian have heightened meaning.

Young has seen first-hand how gentrification has impacted H Street. He said rent prices were under $1,000 when he moved into his home, but a studio apartment now often goes for around $2,000 or more. In the same vein, median income has skyrocketed in his more than two decades living on 4th St. NW.

Only recently has the government cared about developing the neighborhoods, according to Young.

“Neighborhoods like this were neglected by the city and the federal government. It was just allowed to transform into a ghetto,” he said. “All the things the city is doing now is for the new people. They didn’t do any of this stuff — they didn’t keep the streets clean, there was no good policing, there was no nothing. No grocery stores. But when the new people come in, they get everything.”

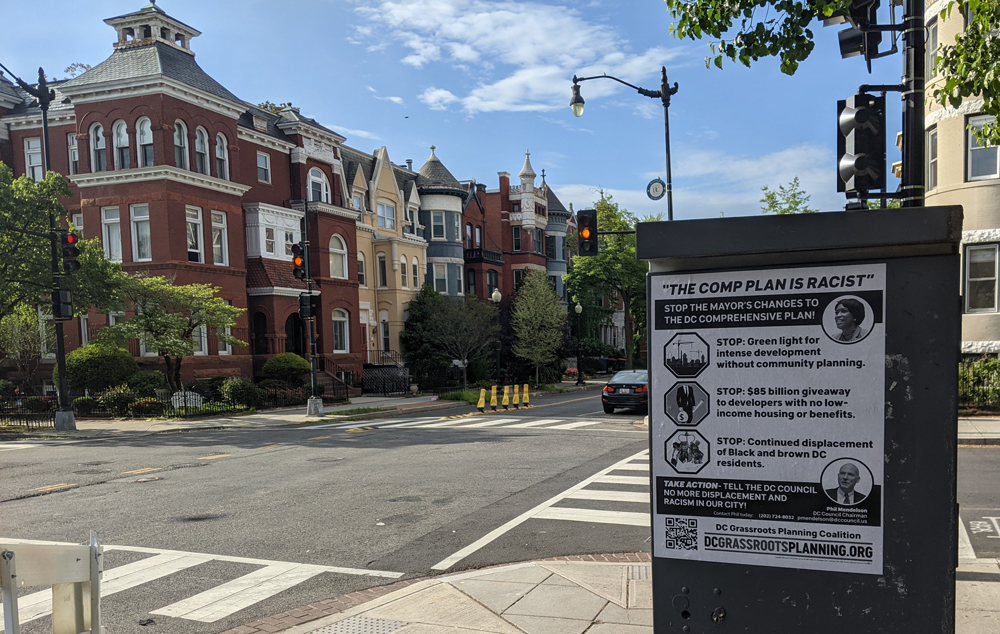

Young cited that when he moved into his home, the closest grocery store was a mile and a half away. Now, there are at least four within walking distance. A study published in March of last year by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition found that D.C. had the highest rate of gentrification by rate of eligible neighborhoods in the U.S. from 2000-2013, resulting in more than 20,000 Black residents being displaced.

One of Young’s many photos features the carryout Horace and Dickies at 12th and H Street NE, which closed on March 1 after 30 years of operating. The owner told ABC7 the landlord wants the property and that the city has towed and ticketed their customers away.

A similar neglect occurred within Barry Farm, which — aside from a small portion that was designated a historic landmark — is set to be demolished and redeveloped under the New Communities Initiative that aims to “transform the public housing development into a mixed-income, mixed-use community.”

Rolark Barnes, who has been the publisher of The Washington Informer for 26 years, has also noticed the changing communities. She mentioned 9th Street Northwest near Florida Avenue as an example of an area she used to spend a lot of time in but has since transformed.

“It’s a completely different community,” she said. “Gentrification also makes me ask, ‘How was it so easy for folks to come and reform neighborhoods or reconstruct neighborhoods, and why was it so difficult for those who lived in those neighborhoods to create the kinds of quality of housing I’m sure they wanted but couldn’t get?”

For as long as Young has been photographing change in the H Street Corridor, the Office of the Deputy Mayor for Planning and Economic Development has been tasked with planning city-sponsored development projects. When asked about the accuracy of Young’s perspective, DMPED acknowledged “the impacts of a growing city.” A spokesperson emphasized that the District’s economic development programs and initiatives are developed with equity and inclusion at the forefront.

Projects include building affordable housing or space for local business owners, providing public resources like parks and libraries, and courting new businesses such as grocery stores. Part of these efforts include trying to mitigate the negative side effects that often come along with new investments, including displacement.

DMPED added that since coming into office, Mayor Muriel Bowser has invested more in affordable housing per capita than any other jurisdiction in the country, investing more than half a billion dollars into the Housing Production Trust Fund. In May 2019, she set a goal to build 36,000 new homes by 2025, 12,000 of which will be affordable. Five months later, a report released by the Office of Planning — which is supervised by DMPED — outlined where those new units should go, making D.C. one of the first cities in the United States to set affordable housing targets by neighborhood and examine the barriers and opportunities in each area.

“Gentrification is taking place all over the world. It’s not just in the United States. It’s not just happening to Afro-Americans and Latinos,” Young said. “I think that the world is experiencing a shift in populations.”

[Read More: Barry Farm residents fear displacement as housing authority reconfigures plans for decade-old redevelopment]

When Young visited Barry Farm, he noticed makeshift memorials with bottles, teddy bears and candles had been left behind in the backyards of some of the buildings, commemorating those who were killed in the neighborhood. Things such as shoes and Bibles were left behind, too.

“When people left, it was almost like they were escaping. Some people left and just left everything in their apartment. Some people left and they just took some things,” Young said. “It wasn’t what you expected. It was like something tragic had happened and they felt that they had to just get out.”

He began collecting the pieces, and the head of construction allowed him to take some of the fencing from the neighborhood.

Months of gathering provided the makings of an art piece in tribute to the former residents. Young mounted the bottles on top of the fencing to symbolize the killings that had occurred in Barry Farm. A red stain on the wood represented the blood that was spilled; a similar yellow splotch was indicative of the yellow tape at a crime scene; and the bottles lying on their sides depicted those who were slain.

While the Smithsonian didn’t take any of Young’s found items, he said they’ll weigh doing so in the future. Meghelli, the senior curator, said that while there are no concrete plans yet to exhibit Young’s photos, they will likely be available to view online after a “lengthy” cataloging process.

“This is great for me personally because all of my life’s work I know is in a museum, being taken care of properly,” Young said. “And at some point it’ll be discussed, exhibited. So this is a great day, a beautiful day.”

When Meghelli visited Young’s home on Feb. 6 to pick up the photos, he saw firsthand the importance of what Young had captured over the years. He said the photographs show the contrast of the city that once was and the city that is becoming a reality. They hold a “special significance,” Meghelli said, for capturing that moment in time.

And now those photographs are preserved with the Smithsonian — a “dream” for Young as he continues to document his home and his community being turned upside down.

“You know what’s the most important part of this, I’m telling this story — a Black person who lives here and has witnessed the change. This is my story.”

The Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum re-opened in October after several months of renovations. The “A Right to the City” exhibit about gentrification will be on display in the main gallery until April 20 and related events are being held through the District in partnership with the D.C. Library until Aug. 5. Many of Joseph Young’s photos are visible online.