Dele Akerejah sits in his small studio, snippets of construction paper and newsprint flying off his scissors in a constant flurry of confetti as he assembles the latest installment in his series of espionage-themed graphic novels, L’Escroc.

As he narrates the tale of a man struggling to escape a seedy underworld of crime and corruption, Akerejah is in some ways telling his own story. The aspiring artist and businessman’s journey from shady hustler to legitimate entrepreneur has wandered through a maze of international drug smuggling syndicates, homeless shelters, college classrooms, cyber-prostitution rings and failed sandwich shops in a twisting tale even more incredible than the fiction he writes.

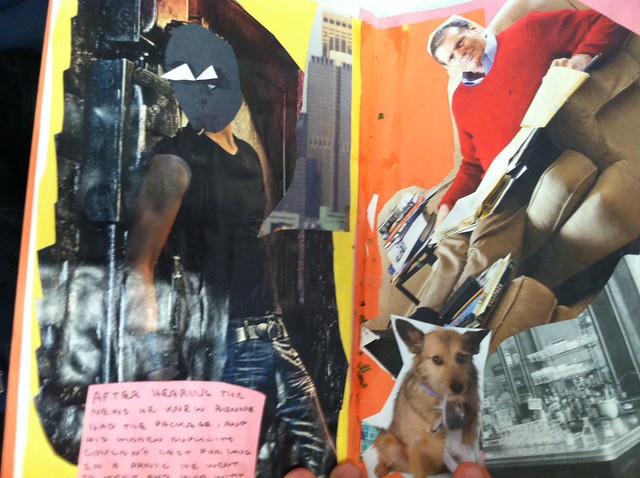

The graphic novels, created as a promotional release for Akerajah’s fledgling arts and leisure company, follow the adventures of Toussant, a masked protagonist who, after unwittingly selling his soul to an evil crime organization in exchange for fast cash, must do their dark bidding in an attempt to break from his own mistakes.

Each episode is encapsulated in a handmade collage booklet, a medium Akerejah describes as “collage artistry.” Toussant dashes through a world of construction paper and magazine clippings, dueling rival spies enlisted from underwear ads or Soviet storm troopers recruited out of Newsweek.

“I was looking for a way to harness both my skills as a writer and my sense of aesthetic in one synergy, and this was the medium I found,” says the 28 yearold New Jersey native.

The plot of L’Escroc, whose title is a French word roughly translated to hustler or trickster, is similarly cut and pasted out of the pages of the artist’s own life.

“[Toussant] is sent on missions that are not dissimilar to things that I’ve heard of or may have been involved in,” says Akerejah, who adds that describing the series as a highly fictionalized autobiography “would not be inappropriate.”

Akerejah claims, for example, that the novels’ fictional Honey Lab Syndicate is based on a drug smuggling cartel he was involved with during the late 2000s. After a failed business venture and subsequent bout of depression in ’06, Akerejah says he “went underground in a deep way,” signing on to help transport narcotics from South America to the East Coast. Initially a low-level mule, he claims to have moved quickly up the ranks to become a “supervisor.”

“I was handling other people, picking up money, acting as a financial consultant, things like that.”

The business side of the organization especially fascinated Akerejah, whose dream of starting his own company has been plagued by disappointment and setbacks. In 2006 he dropped out of college after his sophomore year to focus on launching a sandwich truck business, but the company quickly went under.

After leaving the drug syndicate, Akerejah continued pursuing his business aspirations, though in shadowy ways. In 2008 he says he began operating an online escort service. Serving as a liaison, he would place advertisements on the internet, then arrange rendezvous between clients and prostitutes. He claims the women could get “ten times the price through the internet then what they could get on the street,” a profit he would take a 50 percent share of.

It was during this time that Akerejah first experienced homelessness. Still owing investors from his sandwich business and the university for unpaid tuition, he found himself in a mounting pile of debt and unable to pay rent. In some ways, however, Akerejah says being homeless was a liberating experience.

“Being homeless allows a person a certain freedom. There’s a certain ability to go without, an ability to not need, that allows you to live aristocratically, in a sense,” he explains. “It let me focus on what I really wanted to do.”

The result of Akerejah’s re-prioritized focus has been the founding of his most recent business venture, a vaguely defined online retailer called The Dopamine Clinic. The company is still in the early development stages, but Akerejah says he intends for it to become “an arbiter of pleasure through art, taste, fashion, lifestyle events, and writing.”

The identity of the company is hard to pinpoint even for Akerejah, who compares its “vaporous nature” to the sitcom Seinfeld, the show about nothing. Revenue will theoretically come from a combination of art and clothing retail and the provision of service components like emcee and bartending rentals.

Akerejah envisions a core group of artists and designers working out of a Warholian studio to create everything from paintings and novels to films and music albums.

The nature of the Dopamine Clinic may be enigmatic, but legally it is quite tangible. Akerejah has filed it as an LLC and accumulated all of the documentation essential to any business, including cash flow statements, market analyses and a tax identification number.

“Its an actual company,” he asserts.

Notably absent from the wide variety of products and services The Dopamine Clinic plans to offer are the illicit wares and activities that were a focus of Akerejah’s past ventures. Contrary to the dubious connotation of the company’s title, Akerejah says he has phased out all of the gray areas of his business, a transition he likens to hip-hop legend Jay-Z’s evolution from inner-city drug dealer to platinum selling musician and millionaire business mogul.

With three of the proposed seven novels completed, the L’Escroc series remains unfinished, and Toussant’s fate undetermined. Akerejah’s fate also hangs in the balance. Like his main character, he continues his struggle to escape the consequences of crime and greed.

Perhaps not as dramatic as Toussant’s deal with the devil, the author sees his illegal activities as having had similarly binding consequences.

“I think my homelessness is me paying for that fast money. Like my karma.”