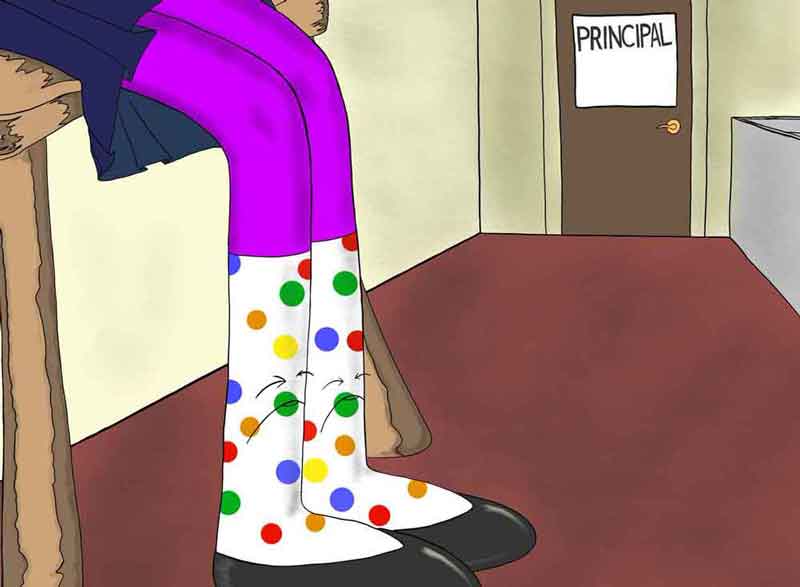

Like many new middle schoolers, the girl with the polka-dot socks walked to school on the first day of sixth grade with butterflies in her stomach. She hoped to make some new friends. Most of all, she hoped she wouldn’t get in trouble.

Her school required all students to wear black, white or flesh-colored socks. In line with their policy, school staff handed the girl a detention slip for violating the dress code, according to Michelai Lowe, the pre-teen and teen program manager of the Homeless Children’s Playtime Project

The girl called Lowe from her school’s main office and asked her to fetch a pair of white socks. HCPP provides unhoused and low-income children with a safe space for recreation and socialization,

Most schools provide a one-week grace period before enforcing the dress code. Lowe said the girl, whose family declined to comment, walked in with this grace period in mind, only to be punished on her first day.

“She has an older brother who also attends the school, so she understands the dress code,” Lowe said. “I guess they’re like a boot camp, trying to set the tone for the rest of the year.”

The girl’s school gave her a gift card to purchase the proper uniform. Later that week, Lowe drove out to Maryland to buy socks at the school’s partner store. When Lowe got there, the gift card didn’t work.

“To their credit, [the school authorities] didn’t know there were going to be issues,” Lowe said. “They’re trying to help our families, but at the same time they have other roles that they need to fulfill as well. So our kids kind of get left in the dust.”

Three quarters of public and charter schools in the District now require uniforms, and according to a Street Sense analysis, some uniforms cost as much as $60 dollars each. The average D.C. public school uniform costs $28 for boys and $32 for girls.

For wealthy students, this kind of expense is manageable, but acquiring uniforms can overburden unhoused families according to Jamilia Larson, the founder and executive director of the Homeless Children’s Playtime Project.

“You’re wearing your family’s economic situation,” Larson said. “The sibling of the girl with the polka dot socks — he had to wear his uniform, but his mom couldn’t afford to buy a whole new wardrobe this year. So he’s wearing uniforms that are too small.”

Although schools are mandated under federal law to provide supplies for unhoused students, Larson said school uniforms often reach those students after the school year begins.

Nicole Lee-Mwandha, the Office of the State Superintendent of Education’s homeless education director, said delays can occur because local nonprofits and charities such as Neediest Kids and Focus DC typically start their supply distribution after the school year starts. Homeless Children’s Playtime Project also raises donations for students at the beginning of the year.

Lee-Mwandha also said schools that have supplemental funding available to them through federal grants and local subsidies often don’t use those funds for unhoused students. Extra funding typically comes from three sources, two of which are federal: McKinney-Vento grants and Title 1 subsidies; in addition, there is some local funding for students who are “at-risk” of not graduating.

According to the U.S. Department of Education website, schools can apply for a federal grant under the 1987 McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act as long as they establish a “homeless liaison” caseworker to post public notices and inform unhoused families of their children’s right to education. Lee-Mwandha, who supervises these caseworkers, said they must remove all barriers to education for unhoused children by providing them with uniforms and transportation assistance.

A school can also qualify for Title 1, Part A funding if more than 40 percent of students receive a free or reduced-price lunch. The District’s 115 public and charter schools received almost $15 million in Title 1 funding for the 2016-2017 school year, according to D.C.’s Open Data Project. Congress approves budget for the U.S. Department of Education, which then allocates grants down to each state.

Finally, at-risk subsidies are determined within the city budget that D.C. City Council votes on every May before the fiscal year starts in October. At-risk money targets unhoused students, foster-care students or students who have repeated a grade one or more times. For the 2016-2017 school year, D.C. Council approved more than $47 million for at-risk programs.

Left: Projected 2016 At-Risk Enrollment by School. Right Projected 2016 At-Risk Funding By School. Larger circles represent more at-risk enrollment or at-risk funding. Maps created with Tableau.

However, a significant share of that at-risk and Title I money may not follow unhoused students to their schools. Mary Levy, an education fiscal policy consultant and former researcher at the D.C. Fiscal Policy Institute (DCFPI), said schools often dip into supplemental funds because their core programs have not received enough funding.

According to a DCFPI analysis conducted by Levy and co-author Soumya Bhat, 32 percent of at-risk money for the 2015-2016 school year was used to fund core programs, and not to target at-risk students. For the 2016-2017 school year, that number rose to 47 percent, which means $22 million of at-risk money was allocated to programs already otherwise funded by the District.

“At-risk funding is supposed to supplement funding that schools otherwise have access to,” Levy said. “Something you often hear in education circles is that at-risk funds must ‘supplement not supplant’ standard funding.”

Levy also said that under the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010, all students at schools with at-risk percentages greater than 40 percent automatically receive free or reduced-price lunch. U.S. Education Department auditors then record these schools as having a 99 percent free or reduced-price lunch population, which means more schools receive Title 1 subsidies.

“It would be nice to think that the federal government would provide more funding as more students are identified as “economically disadvantaged,” but that has not happened,” Levy said. “DCPS has had roughly the same amount of Title I funding every year since 2011 and Congress has appropriated roughly the same amount for the entire nation since then.”

When schools can provide financial assistance to students, it’s not always enough to meet basic needs. Ralonte Hill, an unhoused student at Eastern High School, sued the District of Columbia because the school did not provide him the special education and transportation assistance to which he was legally entitled.

Hill said during several interviews with school officials that he often skipped school because his uniform was “too dirty” or because he didn’t have “the right color,” and because the D.C. Metro card the school gave him only worked at very specific times. Eastern provided him with one uniform. When he requested more uniforms, school officials said they would allow him to wash and dry his uniform at school, but told him he would have to look elsewhere for more clothing.

His case was decided in August 2016. D.C.’s District Court awarded Hill an entire year of compensatory education at New Beginnings, a private vocational school in the District. Hill could not be reached for comment.

According to data gathered by the U.S. Department of Education, Hill was one of the 30 percent of unhoused students in the United States who skipped school last year because they lacked the proper attire. One other case regarding DCPS’s treatment of an unhoused student was filed in 2016

Lee-Mwandha said she has directed several training sessions for caseworkers where she told them to advocate to their school leadership to use at-risk funding for unhoused children. Nonetheless, she said schools that cannot provide their unhoused students with uniforms must commit them with what they have.

“There’s no getting around it: when a child is experiencing homelessness, he or she should not be singled out and stigmatized for it,” Lee-Mwandha said.

Larson concurred with Lee-Mwandha’s statement: “The students shouldn’t have to pay the price for the system not being ready. If the system’s not ready, why would we expect the children to be ready?”

Levy said one solution to insufficient funding for low-income or unhoused students could lie in budget reductions for DCPS’s central office. For the 2016-2017 school year, D.C. City Council approved a budget that would give 5 percent of overall funding to DCPS’s central office.

“The question is this: do we really need all of these people to look over the shoulders of teacher and principals?” Levy said. “Could some of that money be spent on at-risk children?”