Community for Creative Non- Violence (CCNV) and a half-dozen children from ages four to 12 are wrapping up their weekly tutoring session. They are scattered throughout a living room/ conference area, which at all other times of the week is reserved for the shelter’s staff.

A 10-year-old girl plays Trouble with her mentor; an eight-year-old boy runs around shirtless, arm stretched like an airplane; and another boy, reads to his mentor the Dr. Seuss favorite, “Are You My Mother?”

Once they leave this space — the only area in the warehouse size shelter where they can truly play once a week — they will go upstairs to their homes. These homes, or “cubes,” which they share with the rest of their family and perhaps another, are just big enough for six beds and one or two bookcases, with just a thin curtain separating them from their neighbors.

Though these crowded, bleak accommodations were clearly never meant for children and technically illegal under D.C. law, they have turned into the last resort for homeless families in Washington. With the number of families seeking shelter last year reaching record numbers, surpassing 2,000, the city’s homeless services are turning to CCNV. The city has started referring mothers there, despite the Department of Human Services’ outrage and removal of families from this shelter three-and-a-half years ago. Now CCNV’s family space is constantly at maximum capacity; it currently has 13 mothers and 30 children.

Advocates agree that the city is doing little to improve the situation for these children, and not nearly enough to get these fathmilies into appropriate transitional or permanent housing. But until the District takes action, CCNV’s director Terri Bishop says she will do what she can for families. “The only thing we can do is to give them a bed,” she said. she said. “We are trying to help them get out as soon as they can, but there are so many barriers on the outside.”

Bishop said that mothers who come to CCNV are increasingly referred there by the city’s central intake office for homeless families – known as “25 M” because of its location in Southwest – but some still come on their own. Generally, these families have an immediate need for shelter, she said, and many of them are either not D.C. residents or have recently been in the shelter system, making them ineligible for services.

One of these mothers, Ramona Hawkins, came to CCNV in the spring of 2002 with her 11-year-old daughter, Chaz, after their home in Prince George’s County burned down. She said that during the first night in the shelter her “knees were knocking,” as she lay in the dark listening to the other women and children just a few beds away. “I didn’t like it and I wanted nothing to do with it,” she said.

Hawkins said that when she arrived, the shelter had absolutely nothing for children in the way of play space, games or even a quiet place in which to do homework. Since June, mentors from a program through Project Northstar have been coming to CCNV on Thursday nights to tutor and play with the children, but when they leave, their books and games go along with them.

But the lack of entertainment for children was nothing compared to the living conditions, according to another mother, Demetria Reeves. She came to CCNV shortly before Hawkins, after she lost her apartment when it flooded. She arrived with two sons, ages nine and 12, a seven-year- old daughter, and one on the way.

“Honestly, I was happy they took me in, but after a while the living conditions were not good,” she said. “Worms came out of the sink; the toilets always look like somebody defecated on them; and there was foul smell of leftover trash.”

She said not only were the conditions bad, so was the company. At CCNV it was an everyday occurrence for children to hear adults curse and see them fight, and occasionally the children would be on the receiving end.

“There was a lot of women who just didn’t like kids and weren’t afraid to let them know,” Reeves said.

Both Reeves and Hawkins and their children moved into homes of their own a few months ago after more than a year each in the shelter. Mothers currently in the shelter declined to be interviewed.

While these mothers and children at CCNV make up only a small portion of total number of families in shelter system, their presence is startling because this shelter was never meant to house families. CCNV, which takes up the majority of the space in the Federal City Shelter building near Judiciary Square, was established in 1984 for single adults. But according to Bishop, the first families started showing up about seven years ago.

In February 2000, when women and children were becoming a regular presence at the shelter, the D.C. government decided to enforce its contract with CCNV that specified that the shelter was only for adults. The Department of Human Services (DHS) shipped all the families out of CCNV to D.C. Village, its largest family shelter. The contract was eventually changed to include children on a temporary basis, but conditions at the shelter changed little.

And it is still technically illegal for families to stay at CCNV, since an outdated law requires families in shelters to have apartment-style housing.

Nevertheless, soon after the District’s crackdown, a new batch of women and children came knocking on Bishop’s door, and she created CCNV’s first official space for women with children in a wing that also housed single women. Though it was not until the last year that families really started flooding CCNV, Bishop said.

She admits that CCNV is no place for children but said that she would try her best to accommodate any family that shows up there. Bishop said that she is adamant about enforcing the no swearing and fighting rules, and that she has tried to get the children play space in another part of the Federal City building, only to have it taken over by the city for another shelter.

“I don’t want children here. This is an adult shelter,” she said. “But if they don’t have somewhere else for them to go, I’m not going to send them back onto the street if I can do something about it.” Szcerina Perot, staff attorney for the Washington Legal Clinic for the Homeless, said that Bishop has little choice but to take in these families. She added, however, that the District, through 25 M, should not be referring mothers to a place that breaks the law and has substandard conditions.

In addition to CCNV’s failure to meet outdated apartment-style shelter law, its basic conditions are not up to the District’s standards for children. The shelter space is incredibly unsanitary, Perot said, and far from what the Child and Family Services Agency, according to its guidelines for child neglect, would consider an appropriate and safe living environment. “There are mininum health and safety standards you want to provide your kids, and D.C. should not be encouraging people to bring their kids in this rat- and roach infested place,” said Perot.

So why is the city referring families to a place that does not even come close to its own standards?

Debra Daniels, spokeswoman for DHS, said that that CCNV is not part of its shelter network and should take in families, but that since Bishop has accepted families, DHS will let them go there when there are no other options.

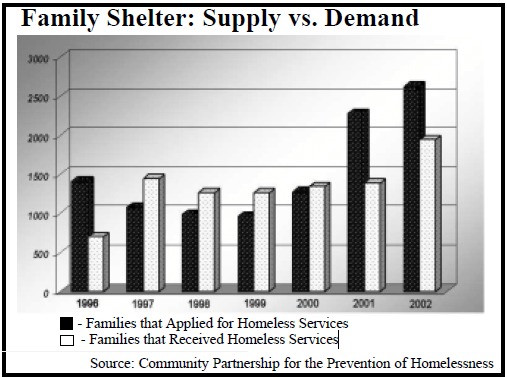

In 2002, 2,278 families, including 5,183 children, applied for emergency shelter in Washington, according to the Community Partnership for the Prevention of Homelessness’s latest statistics. And of these families, less than half – 1,064 – received emergency shelter over the course of the year.

This is up 10% from 2001 and has increased by an astonishing 130% since 2000, according to the Community Partnership, the organization that supervises the shelter system in D.C.

Though the Community Partnership anticipates that this number will grow by at least 5% in 2003, Bishop and others said that the District has done little to find more transitional housing space or to move the women out of the shelters system faster. In fact, though CCNV, like all other shelters, is, in theory, temporary housing, Bishop said it is not uncommon for families to stay there for more than a year.

As for housing programs, DHS provides financial assistance, counseling, and case management services to help families avoid homelessness through the Community Care Grant, according to Daniels. Daniels added that DHS is constantly looking for new shelter space, and wants all families out of emergency shelters.

However, Steve Cleghorn, the Community Partnership’s deputy executive director, said finding more District-sponsored family shelters or transitional housing buildings is unlikely.

“There is a bit of a problem opening up a new emergency shelter for families,” he said. “Not only are there funding issues, but it has just gotten to the point where it’s very difficult to open multi-unit facilities for homeless families. Those days are behind us.”