Rylinda Rhodes was faced with a difficult choice when she was convicted of a felony for killing her abusive partner. She could fight her conviction, but remain incarcerated and separated from her children, or take a plea deal and return to her family. She chose to take the plea, but could not have anticipated how severely her felony conviction would mar her future.

Although Rhodes had marketable skills, she was refused employment, and the job she did find paid such low wages that she lost her apartment. Her children were sent into foster care and she became homeless. A new bill passed by D.C. Council this summer could help returning citizens like Rhodes, who gave testimony at a Jan. 28 hearing, receive support and training to achieve gainful employment after incarceration. However, the prospective program has yet to receive funding from the city.

On July 28, the D.C. Council unanimously passed Bill 21-463, which proposes creating a program for returning citizens to develop the skills to start their own businesses. Sponsored by former council member Vincent Orange, The Incarceration to Incorporation Program Act (IIEP) will provide 100 returning citizens with a business development program that includes a fast-track GED program; classes in math, literacy, and business development training; mentorship and networking opportunities; and investment in businesses run by returning citizens.

The program will also assist students in enrolling in business classes at University of the District of Columbia or the University of the District of Columbia Community College. The Department of Employment Services and the Department of Small and Local Business Development are to operate the program. The law also calls for the establishment of a fund of up to $10 million composed of city and private monies.

The Council approved this legislation subject to appropriations, meaning that there are no funds allocated towards its implementation for fiscal year 2017. Members of the D.C. Reentry Task Force, which suggested changes to the bill before it was passed and advocated for its approval, say they will lobby Mayor Bowser to provide funding in the 2018 fiscal year budget. For now, they are seeking private sources of funding and making the law’s language more specific, according to Task Force member Kevin Smith.

The skills participants learn in this program will make them ideally suited to find permanent employment. “Even if a person doesn’t start their own business as a result of that, those are the individuals that are still more likely to go out and be able to find a position,” said Smith. He hopes that IIEP will allow ex-prisoners to harness their existing passions or skills. “You’d be amazed at the innovation and creativity of the individuals in there. It’s unbelievable.”

This bill has some similarities with the Aspire to Entrepreneurship Pilot Project, a one-year program run by the Department of Small and Local Business Development that began in July and is independent of the IIEP. “The Mayor asked our office to start looking into it,” said Katherine Mereand-Sinha, Manager of Tech and Innovation. Aspire serves 25 returning citizens by providing them with classes on financial literacy and business planning, as well as mentoring and support. Participants also receive a stipend for six months while they try to get their business off the ground.

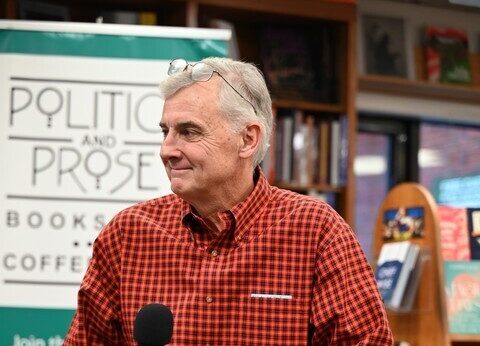

Graham McLaughlin is the Chair of the Board at Changing Perceptions, a nonprofit involved with Aspire that was founded by Will Avila in 2014 so that returning citizens could receive mentoring and support from other returning citizens. McLaughlin said one of the strengths of this pilot is how it draws skills from various organizations in order to provide holistic support for the challenges returning citizens face. According to McLaughlin, the pilot benefits the city’s finances by enabling formerly incarcerated people to contribute financially to business and taxes, rather than increasing criminal justice costs with recidivism. “They’re really putting money into the city coffer’s instead of costing the city money,” he said.

Although the program is new, those involved seem optimistic about its work. “There’s a lot of really hardworking people in the cohort who are showing that with this support you can develop a great plan, who are starting get out there and market and potentially get some revenue opportunities,” said McLaughlin. “All signs point towards success.”

Kimberly Nelson, who participated in the campaign for Bill 21-463 and is performing program evaluation for Aspire as a volunteer, says the cohort seems engaged. Nelson believes programs like these are important because of the employment discrimination that returning citizens face that enables a vicious cycle of recidivism and lack of opportunity. “This is a visionary type of program,” said Nelson. While programs run by nonprofits have taken root across the country, no other city government has taken up the cause of entrepreneurship for returning citizens like the District has, according to Nelson.

Returning citizens face daunting obstacles when they rejoin society. The Court Services and Offender Supervision Agency found that 64 percent of Black ex-offenders in D.C. were unemployed in 2014. This is significant, since 10 percent of D.C.’s population has a prior conviction. McLaughlin can list a litany of challenges facing formerly incarcerated people, from insecure housing to emotional trauma and lack of social support. With a lack of education and experience and facing the stigma of a conviction, finding employment or starting a business becomes nearly impossible. Programs like Aspire and the IIEP hope to change those odds by offering the support necessary to allow returning citizens to thrive on their own.

Many of those who testified at the Jan. 28 hearing in favor of the bill were fortunate enough to start their own business or be employed by a returning citizen. Anthony Pleasant went to prison at age 16 and when he was released at 27 found he was unprepared for the working world. Will Avila, another returning citizen, gave him a job at his company Clean Decisions, giving Pleasant the support he needed to get his current job at a furniture assembly job.

In his testimony, Pleasant described how his lack of experience and financial stability has prevented him from starting his own furniture business. “I live paycheck to paycheck, don’t know how to get a loan, and while I am really good at furniture assembly operations and could run the business, I don’t have the money to start it and don’t have the back end training to get the license, take care of insurance, etc.” Pleasant said. He is now one of the 25 participants in the Aspire Pilot.

As returning citizens like Pleasant learn how to become successful entrepreneurs, supporters of IIEP prepare to ensure that the bill does not remain unfunded indefinitely. Already exploring private sources of funding, Kevin Smith says they hope the Mayor’s Office will include funding in next year’s budget. “If the Mayor does not wholeheartedly support it, and fund it, it’s not a priority of her administration,” said Louis Sawyer, Jr., the chair of the D.C. Reentry Task Force and a returning citizen.

“When that person has employment, it brings on dignity and hope,” Sawyer said.