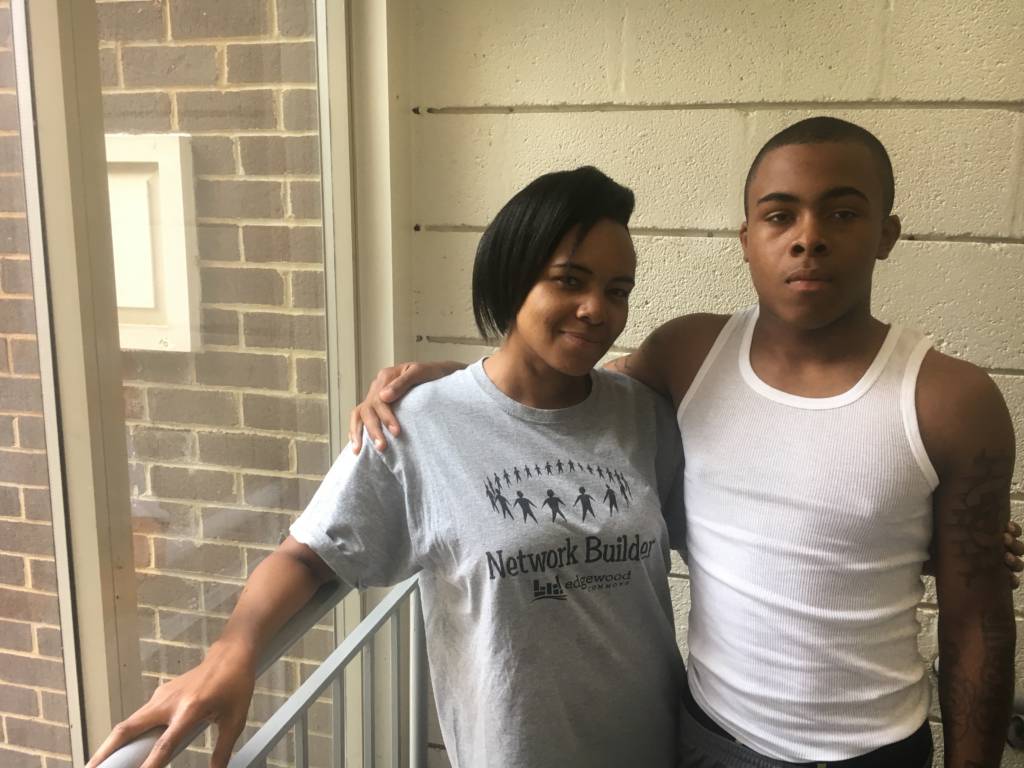

Elijah Payne says June 24 was the best day of his life.

On that Saturday, he graduated from the Capital Guardian Youth Challenge Academy, a highly structured, quasi-military program for at-risk youth. The 16-year-old entered the academy after years of poor school attendance and impulsive behavior.

While the first few weeks were tough, Payne said part of him didn’t want to come home by graduation. Throughout his time in the academy, his mindset and behavior improved. His mother, Cinquetta Williams, said he’s become more affectionate, often coming by the house just to give her a hug.

“He always knew he wanted more for himself,” she said. “He got so far gone, he didn’t know how to reel himself back in.”

The opportunity to do so came when a social worker contacted Williams last year and offered her son a spot in the city’s Alternative to the Court Experience Diversion Program, which gives young people options to avoid arrest. Payne was referred to the program because of excessive school absences.

“At first I didn’t want to comply,” he said. “But then instead of trying to run from it, I figured I might as well go ahead and do it.”

Eventually, his case workers convinced him to undergo a mental health evaluation, which helped him address some underlying trauma from having witnessed his friends die. However, he still wasn’t meeting the program’s requirements, prompting his case workers to suggest enrollment in the CGYC Academy.

The school prepares students for the GED test, which is equivalent to a high-school degree. On his first try, Payne barely missed the required score, but he plans to keep studying to pass the test. While Payne hasn’t officially gotten his diploma yet, the graduation day was a moment of immense pride for him, his mom and their family.

“I didn’t have enough tissues,” Williams said.

Payne isn’t certain about his future, but he has considered joining the Navy. For the next few months, he is taking an auto-mechanic class. Without the ACE program, Payne knows he would have continued on a dangerous path.

“I already know where I’d be — most likely in jail,” he said.

The ACE program matches 10-to-17-year-olds with activities ranging from mentoring to after-school sports that address their individual needs. By completing the program, youth like Payne can avoid formal arrest while decreasing their risk of future homelessness.

Bridging the Gap

ACE was created in 2014 when Hilary Cairns, deputy administrator for the Department of Human Services, recognized a disconnect between youth in need and available behavioral health services. Before then, D.C. lacked options to divert young people from the court system.

Three years later, more than 1,500 young people have been referred to the diversion program, which includes DHS, the Department of Behavioral Health and several juvenile justice entities.

In May, the city released its first strategic plan to end youth homelessness, which lists expansion of ACE as a key strategy and calls it “an evidence-informed and highly successful program.”

The program is largely measured by how youth fare after completing it. Since taking office in 2015, D.C. Attorney General Karl Racine has pushed to give DHS more access to recidivism data, which shows 81 percent of the program’s youth have not been rearrested.

Given the program’s evident success, Mayor Muriel Bowser and the D.C. Council have increased funding for it each year. The city budget for fiscal year 2018 provides an additional 13 ACE staff members. Cairns said the increase in staff needs to coincide with the program becoming accessible to more youth.

“The issue is trying to give more young people the opportunity to participate in diversion as opposed to participating in court and the things that we know are ultimately linked with homelessness,” she said.

From Prison to the Streets

The link between the juvenile justice system and homelessness is partially due to the difficulties youth face after their release from prison. Amy Louttit, a public policy associate for the National Network for Youth, said reentry plans for young people are often nonexistent or insufficient.

“It’s all well and good to make sure they have a roof over their heads, but without the support of services to aid that transition, we’ve seen huge failures,” she said.

Louttit said greater collaboration between ACE and homeless youth organizations such as Sasha Bruce will allow the city to have more success with its plan. A closer relationship between law enforcement and runaway youth programs would also allow city officials to address a pervasive problem: chronic absences from school.

“Programs like ACE can be really useful at digging a little deeper and seeing why those truancy issues are occurring,” she said. “They really help, especially if the young person is experiencing homelessness.”

Forty-one percent of diverted youth were also criminally absent from school, according to DHS data. While ACE prioritizes delinquency cases, such as vandalism or shoplifting, the staff also helps youth with truancy charges when resources are available.

Seema Gajwani, who works on juvenile justice reform in the Office of the Attorney General, said the city has yet to develop a successful method to reduce the number of kids who are truant.

“There’s no evidence that shows prosecuting a young person for not going to school makes them go to school even more,” Gajwani said.

She pointed to resources offered by ACE, such as family-focused therapy, as effective solutions to problems associated with truancy and homelessness.

A Bright Future

Cairns said youth whose crimes are as miniscule as not paying a Metro fare often end up having the greatest needs. Meanwhile, some youth in the program have supportive families and don’t require much attention during their six months of participation.

Young people express stress and trauma in different ways, but they can only enter the ACE program through referrals from the OAG, Metropolitan Police Department and Court Social Services, making it difficult to help those who aren’t in the justice system. Gajwani said strengthening the relationship between ACE and schools would allow more youth to receive the help they need.

“This kind of evidence-based, high-quality intervention to support children and families should not be reserved only for children who end up in the justice system,” she said. “It should be for families and children who need that support in their schools.”

Cairns said the suggestion resembles an existing DHS program, Parent and Adolescent Support Services, that matches young people with resources similar to those in ACE. The city’s new youth plan recommends developing the PASS program.

“I think it’s just an expansion of opportunities for young people outside of the delinquency system, whether they can come in voluntarily by a parent or school referral versus a youth having actually touched the delinquency system.” Cairns said. “There are different ways of getting to us.”

Gajwani agreed, but she said the programs should have a more institutional and visible role in public schools with high truancy rates. With many distressed kids still not receiving help, Cairns is open to ideas about how to use the new ACE staff members.

“The ultimate goal is keeping young people out of the delinquency system whatever way we can do that,” she said.