In 2007, journalist Mary Otto received a tip from a Baltimore-based lawyer at the non-profit Public Justice Center. The lawyer, Laurie Norris, described a low-income mother who was having trouble booking a child’s dental appointment, though under Medicaid, all her children were entitled to dental care.

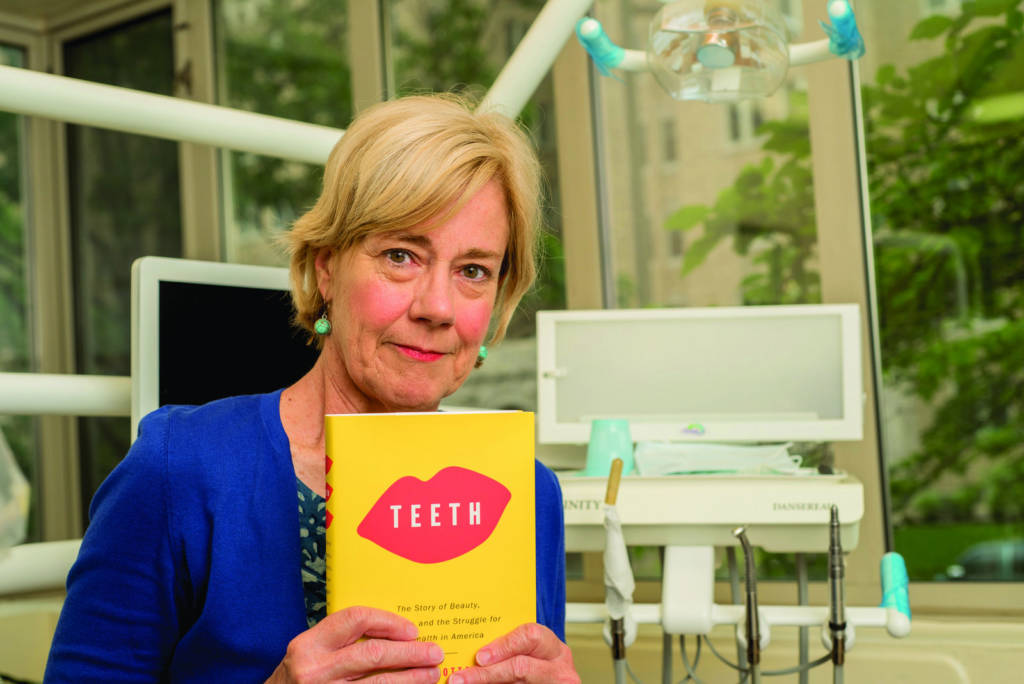

Otto had no idea this seemingly simple story would ultimately become tragic and inspire her reporting for the next decade, eventually leading to her new book, “Teeth: The Story of Beauty, Inequality, and the Struggle for Oral Health in America.”

The lawyer who gave Otto the tip was working on behalf of Alyce Driver, who had a 12-year-old son, Deamonte, with an infected tooth. Driver had struggled to find dental care for her five children and — in a stunning combination of a lack of information, a frustrating medical bureaucracy and even a brief stint in a homeless shelter for the Driver family — Deamonte’s condition remained untreated for too long. Eventually, the bacteria from his abscess spread to his brain. The child was a patient at Children’s Hospital when Otto met the family and wrote about them for the Washington Post.

It was the last week in February 2007, and Otto’s story was already filed and ready for publication in the next day’s newspaper when she called Alyce Driver for one final check-in. That was when she learned the awful news. Twelve-year-old Deamonte Driver had died.

Otto’s detailed reporting on this tragic situation would help lead to Congressional hearings nationally and the creation of the Deamonte Driver Dental Project mobile clinic in Maryland along with a host of reforms that opened up dental health care access to the state’s poor. Members of Congress, led by Maryland’s delegation, fought for, and won, a guaranteed dental benefit for children covered by the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) which now covers about 8 million children from working poor families across the country. The book inspired by Deamonte Driver’s story is a comprehensive examination of the lack of dental health access in poor communities and efforts being made to alleviate the suffering.

Long-time Street Sense readers may remember Otto as editor-in-chief of Street Sense from 2008 to 2014. During that time she also pursued a Knight Science Journalism Fellowship at Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and served as the oral health topic leader for the Association of Healthcare Journalists. Her new book has received high praise in national publications such as the Atlantic and the New Republic and from leaders across the state of Maryland. One of the book’s admirers is Congressman Jamie Raskin (MD-8), who has said that “Mary Otto’s unflinching work on the miserable state of oral health in America gnaws at you like a toothache.”

The book could not come at a more urgent time, as oral health advocates are worried about the efforts underway by the Trump Administration and Congressional conservatives to dismantle the Affordable Care Act and revamp Medicaid, with the future of CHIP and dental benefits at serious risk.

Fresh off a positive review of her book in the New York Times, Otto took the time to speak with Street Sense about her new book and the connection of dental health to poverty:

Street Sense: So much of the Drivers’ predicament had to do with a lack of Medicaid benefits, and disincentives for private practice dentists to treat patients on the Medicaid program. How quickly did it lead to a response from public officials?

Mary Otto: It happened pretty quickly, actually. There was a new governor in Maryland, Martin O’Malley. He was very anxious to confront this problem. The Maryland delegation included Congressmen Elijah Cummings, who squared off with George W. Bush on Medicaid and what should be done with the Children’s Health Insurance Program. Congressional Democrats wanted a guaranteed dental benefit to be part of CHIP, but President Bush had threatened to veto any expansion of the program. Deamonte’s story was a defining moment during the battle on the issue.

Why is it so hard to find a dentist who accepts Medicaid in American cities, where one might assume a dentist shortage wouldn’t be so stark?

Otto: Medicaid providers may not be taking new patients. Medicaid pays half of what commercial insurance pays. [Dentists] say they’re losing money on these patients, so they either won’t take them at all or will only take a limited amount. If most dentists take this approach, you can see where this is going. There’s an access problem throughout the system: I have talked to Medicaid patients that will drive miles and miles just to find care.

Adults, unlike children, aren’t even entitled to dental health under Medicaid; some states do and some states don’t offer the coverage. Fewer than half of children covered by Medicaid actually receive dental benefits. In some cities and states they now have the ability to give basic trainings and fluoride at school and senior centers to really increase the amount of preventive care, but that’s not enough.

How has this lack of access to care affected rural areas?

Otto: In the book, I describe one particular clinic in rural Western Virginia that had been organized by Remote Area Medical. They are a nonprofit group who originally provided medical supplies and services to developing nations until the founder of the organization, Stan Brock, realized that there were communities right here in the States that were in dire need of services. So they started airlifting supplies into some of these communities in the very western tip of Virginia: gauze, dental chairs and other medical instruments.

So they’ll put out a call to volunteer practitioners — physicians, doctors, nurses, hygienists, medical students. [The volunteer practitioners] converge on this community for a weekend of care. They provide all kinds of care specialists that can treat people with diabetes, breast exams, physicals. But the line for dental [treatment] is always the longest. One family drove all the way from Florida to get care from [the weekend clinic in rural Western Virginia].

What impacted me the most was just how much pain people were in. Think about the pain you get when you have a bad tooth problem, and imagine having to travel across the country to get care. People had to sleep in their cars to make sure they got in line. But you never forget the pain they’re in. Hundreds of thousands of teeth are extracted at these events. The disease is so advanced that it almost always leads to extraction.

One issue that I keep seeing in reading the coverage is how dentistry has become separated from the healthcare industry. How did that happen?

Otto: Well, I found out from my reporting that it happened in Baltimore Maryland, about 30 miles away from where Deamonte had lived. Back in the 1840s, the first dental college in the world was founded in Baltimore by two dentists who were self-trained — which was normal back then because [dentistry] was much more like a trade or a service that could be performed at a local barbershop.

But this was also a time when medicine was becoming much more scientific. [The two self-trained dentists] thought dentistry was worthy of professional status so they went to the University of Maryland College of Medicine to talk about including a program for dentistry but, as the story goes, the skill of dentistry had no interest for [the people at the College of Medicine]. So [dentists] started their own school, and a whole separate profession grew from there — with a separate educational system, a separate financial system. So you have this chasm between the medical industry and the dentistry industry, and patients have to bridge that gap alone. If you’re poor and don’t have out-of-pocket money, there are real barriers to care.

How has the industry been regulated?

Otto: Organized dentistry has guarded the marketplace for dental services very carefully. By protecting their autonomy and authority to provide care in the public practice system, they often find themselves at odds with advocates’ efforts to expand care through alternative workforce models, whether it’s government officials or activists in the public health space.

The dental therapist model is a good example of one of these models that could work. Here you have a mid-level technician with just 2 years of schooling and half the price of a regular dentist, who can meet basic needs in poor communities that don’t have dentists. They can fill teeth and provide basic extractions. [Dental therapists can provide] a narrow range of badly needed routine services. The idea is maybe this model is reaching people who don’t have access to dentists. [Dental therapists] can meet the needs of Medicaid patients that dentists say they’re losing money on. They’ve been using this model in tribal communities in Alaska and Washington state, and in Minnesota, but it has yet to catch on at the national level.

Right now, it appears the economy of private practice can’t bridge the gap to the more than 100 million Americans who have barriers to care. Public health officials and leaders have recognized for a while that we need to find a way to expand care to those people. Organized dentistry has pushed back on the idea, saying there are enough dentists around to meet the need. That tension is alive and well today.

So most dentists don’t want to lose money by treating Medicaid patients, but also don’t want dental therapists to be empowered to fill the gap in the market?

Otto: Dentists have fought to preserve the autonomy and professional authority of their profession, which is their right. They do have a lot of expenses: many graduate [with] a quarter million dollars of debt; they buy equipment; they hire staff. They [may] count Medicaid as their overhead, but that doesn’t always work. There are other ways that might be more economical for everyone.

Why has this issue been so underreported?

Otto: I think part of it is that for people who have private benefits and enough to pay out of pocket for care and who live in affluent areas where dentists are competing for their business — they just have no idea of the millions of others who cannot get care. Meanwhile, a third of Americans struggle to get access to care because they are poor and live in underserved areas, or they have minimal public insurance that doesn’t get them far. This topic can be invisible for some people and a life-changing dilemma for others.

What’s the connection between dental care and poverty? What can be done about this locally?

Otto: Well, for one, there’s the lack of care. There are a couple of good places that provide care locally but there’s never enough.

Then there’s the problem that a person can be stigmatized for poor dental health. With a missing tooth, it might be harder to get a job and get out of poverty.

The problem with oral health also affects the vendors at Street Sense. Many are in immense pain from the lack of care. In the book I quote a Street Sense vendor, Aida Peery, who courageously shared the story of her own struggle with oral disease. She spoke for millions of low-income adults who do their best to do their daily work and overcome poverty in spite of that painful burden.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity. Here’s what Artist/Vendor Sheila White had to say on the subject.

Reduced Fee and Free Dental Care in the District of Columbia (via dcdental.org)

Mary’s Center for Maternal & Child Care

3912 Georgia Avenue NW

202-545-8023

Mondays – Saturdays | 8:30 a.m. – 5:00 p.m.

www.MarysCenter.org