Three years after the launch of a new system to more effectively end homelessness in Washington, D.C., Coordinated Assessment and Housing Placement leaders are re-evaluating its effectiveness in light of expanded federal requirements for the program.

[Read more: District streamlines the road to housing]

With the publication of a notice in January establishing new U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development guidelines for CAHP, or coordinated entry, to be implemented no later than Jan. 23, 2018, major U.S. cities dealing with high rates of homelessness are focusing on issues of data collection, prioritization and collaboration.

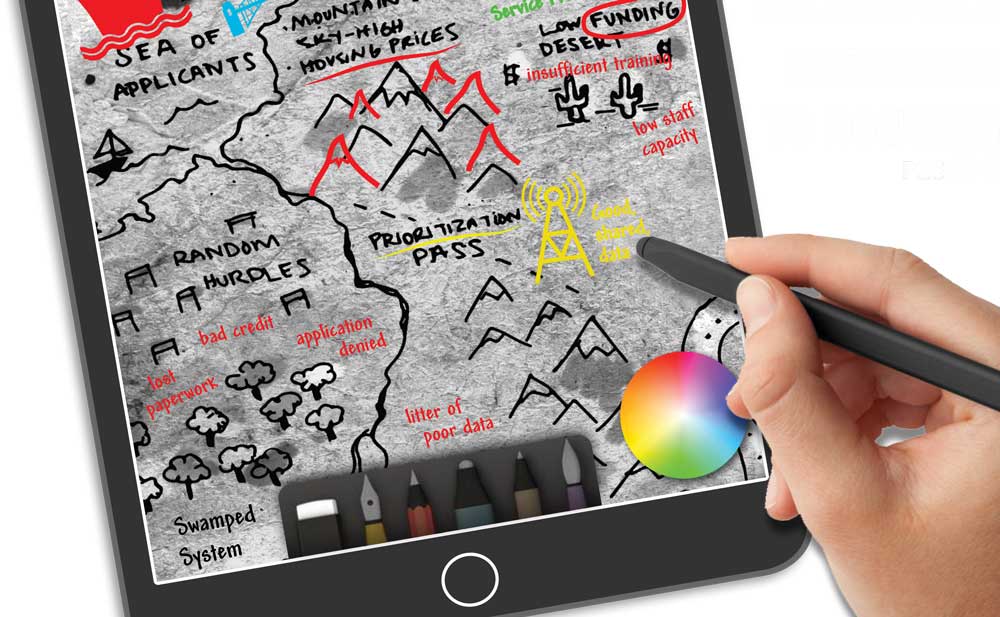

Coordinated entry was launched in D.C. in February 2014 after the system was successful in housing many of the District’s homeless veterans the year before. It is an approach to administering services to homeless individuals that requires many different resource providers within a community to coordinate with each other and place the most vulnerable individuals at the front of the line for available housing. It is a triage system that typically consists of outreach, an assessment of homeless individuals’ vulnerability, coordinated case management and placement into appropriate housing.

Many cities had been operating coordinated entry systems that arose independently of federal oversight. When the United States Interagency Council on Homelessness released a federal plan called “Opening Doors” in 2010, coordinated entry sprung up in major cities to facilitate ending veteran and chronic homelessness by 2015, to end family and youth homelessness and to lay the groundwork to end all homelessness by 2020.

“It took away from the first-come, first-served basis or other factors, like whether you had a good case manager or not,” said Sarah Honda, assessment and housing navigator at The Community Partnership for the Prevention of Homelessness. “Instead of people being placed on a waiting list and being moved around, they would be placed on a centralized registry.”

Stagnation

The amount of homeless individuals being housed dipped down for the first time in 2016, and at the same time assessments for rapid rehousing and permanent supportive housing increased.

Leaders at the most recent D.C. Interagency Council on Homelessness CAHP committee meeting criticized that much of the chronically — but not as medically vulnerable — homeless people in D.C. are being left unserved.

Community leaders expressed their clients’ and their own frustrations at the need for prioritization due to limited resources. “If you don’t have a house, you don’t have a house,” said Kally Canfield of Friendship Place.

The key question at the D.C. CAHP meeting was “Where do we see prioritization working and not working?”

On top of the persistent lack of affordable housing and resources in the District, other ongoing challenges identified were a need for more proficient staff/volunteers and, consequently, more quality data collection.

More Staff, More Training

The District’s primary goal is to house individuals in the most pressing medical danger. However, questions arose at the meeting about the strength of the assessment tool.

New York City and Los Angeles have both been implementing coordinated entry systems for about the same number of years as the District and have encountered similar challenges for prioritization. Both cities have significantly more people experiencing homelessness than in the District, though the nation’s capital retains the highest rate of homelessness per capita, according to a December 2016 report from the U.S. Council of Mayors.

D.C., Los Angeles and New York City all use the Vulnerability Index and Service Prioritization Decision Assistance Tool to rapidly assess homeless individuals and families to determine what services they may need and be able to access.

VI-SPDAT allows outreach teams to rank individuals based on health and fortitude by assigning them a number from 1 to 20. The higher the score, the more “at-risk” an individual may be. From there, it is determined what level of intervention that person needs, such as permanent supportive housing or one-time assistance.

D.C. community leaders have found it difficult to prioritize tie-breaking factors when two equally vulnerable individuals are in need of housing. They considered whether or not the length of stay in a shelter, or time being homeless, should be used as a first tie-breaker when prioritizing people for permanent supportive housing. The length of time spent homeless is currently a third prioritization factor, behind severe medical needs and unsheltered sleeping locations.

Los Angeles County has faced similar challenges in prioritizing chronically homeless people based on vulnerability, according to Meredith Berkson, a leader of coordinated entry efforts on behalf of People Assisting the Homeless in Southeast LA, one of the eight regions the county is divided into.

Since Los Angeles’ coordinated entry system focused on veterans and chronically homeless people in 2013 and 2014, fewer resources were available to individuals considered less vulnerable. Even though data suggested that veteran homelessness and family homelessness rates were decreasing, it did not account for individuals who were not prioritized in early implementation. This realization prompted Los Angeles to invest in rapid rehousing as a short-term subsidy for less vulnerable individuals.

“We saw that folks who were less acute — not chronically homeless — were becoming chronically homeless because there were no resources for them. So we saw people decompensating on the streets,” Berkson said. “Having everyone in the system understanding now that yes, we are using prioritization, but, what does that mean for populations that aren’t prioritized — and then using that to advocate for the resources that we need for both vulnerable and less vulnerable individuals. That was a great thing.”

High staff turnover and lack of extensive interview training are challenges in any region for gaining an accurate initial VI-SPDAT score, according to Melissa Marrone, coordinator of the Housing and Homeless Coalition of Central New York.

Those administering the VI-SPDAT are required to undergo basic training, but Marrone emphasized the need for additional training, such as motivational interviewing and trauma-informed care, to adequately prioritize someone’s vulnerability the first time they are entered into the system.

She explained how some Central New York communities, prior to the use of VI-SPDAT and then for a while still afterwards, would cherry-pick and house people who were not as vulnerable as others.

“There were 3 or 5’s going into rapid rehousing or even public supportive housing and … I had to monitor the program and provide oversight,” Marrone said. She described how she even saw some people with graduate degrees and yearly incomes greater than her own inappropriately going into housing over other “hard-to-serve” people, those who may be unwilling to receive services or are difficult to keep in contact with.

Regardless, Marrone and Central New York have reported success. The region began with and still uses chronic homelessness as one of the first tie-breakers in prioritizing its clients. With Central New York having met federal guidelines for ending veteran homelessness, Marrone looks forward to the goal of ending chronic homelessness by the end of this year with plans to hire more staff in order to provide more oversight and workforce power.

The Problem with Prioritization

A second key point of discussion at the D.C. CAHP committee meeting explored the time period between when a person initially becomes homeless and then becomes “entrenched in the system.” In relation to making the best use of limited resources between rapid rehousing and permanent supportive housing placements, community leaders questioned the lack of federal evidence or studies on whether there is a critical period of time to seize and provide the most mediation before a person becomes chronically homeless.

Los Angeles is currently undergoing the launch of a new data collection system with the aim of more reliably documenting the time it takes for someone to get matched to housing, how long people remain in the system and how service providers are matching individuals to resources.

“The biggest success of coordinated entry in Los Angeles has been the level of cooperation and coordination that’s happening between agencies,” Berkson said. “It’s an exciting time for there to be more accountability because we’ve really built a good collaborative system and now looking at ‘OK, where do we need to improve from here?’ using data and that’ll be a good thing to help the system move forward.”

This difficulty intervening with housing in a timely manner gives credence to New York City’s recent switch toward a “prevention-first” model to combat its high rate of homelessness. NYC’s mayor ordered an operational review of New York City’s homeless programs in December 2015, which drew out a plan to overhaul the system and expand its homeless prevention network services so that clients at risk of homelessness are proactively targeted in order to prevent them from entering shelters.

While a similar prevention model is planned out in the Homeward D.C. (2015-2020) strategic plan, prevention is not the primary focus of the District’s coordinated entry housing-first model.

Collaboration is Key

Virtually all service providers now collaborate in the District’s coordinated entry system. One hundred and four unique agencies have received training on how to administer the VI-SPDAT through D.C.’s coordinated entry system, according to the published January 2017 update, with eight organizations recently doing the bulk of the work.

Berkson cited large team collaboration and the support of local government as helpful in Los Angeles’ system. “That’s a huge step in the way of making sure that people are getting the best possible care and that services are connected and speaking to each other,” she said.

In Central New York, Marrone cited two key things that are a part of their growing coordinated entry success: a large number of motivated and dedicated people and a well-functioning street outreach team.

“We have a monthly … meeting where 60 [people] and over come in — we have to really pack people in … and there are other committees besides the monthly meetings that are just as full,” she said.

Currently, Marrone and another administrator provide oversight and make sure that housing providers adhere to the vulnerability index registry. Notably, the Central New York’s agency agreement is a much more binding contract than that of the District’s in which provider agencies must date and sign to specific terms and conditions that explicitly details time-sensitive responsibilities.

In D.C., a collectively agreed-upon, “organic” policy and procedures was published in 2016, acting as more of an instructional guide on how to administer and enter in assessments and on the roles of assessors, attendees of case conferencing meetings, housing guide specialists and housing providers.

As the District moves ahead with the coordinated entry system and ongoing discussion on the future of its prioritization criteria, the community leaders shifted the focus back to what could be done: “We need to show that we can make the best use out of these little resources that we have. That’s how we get more resources.”